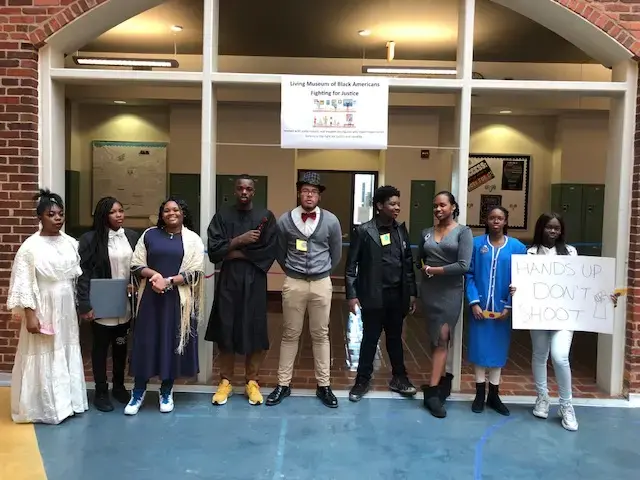

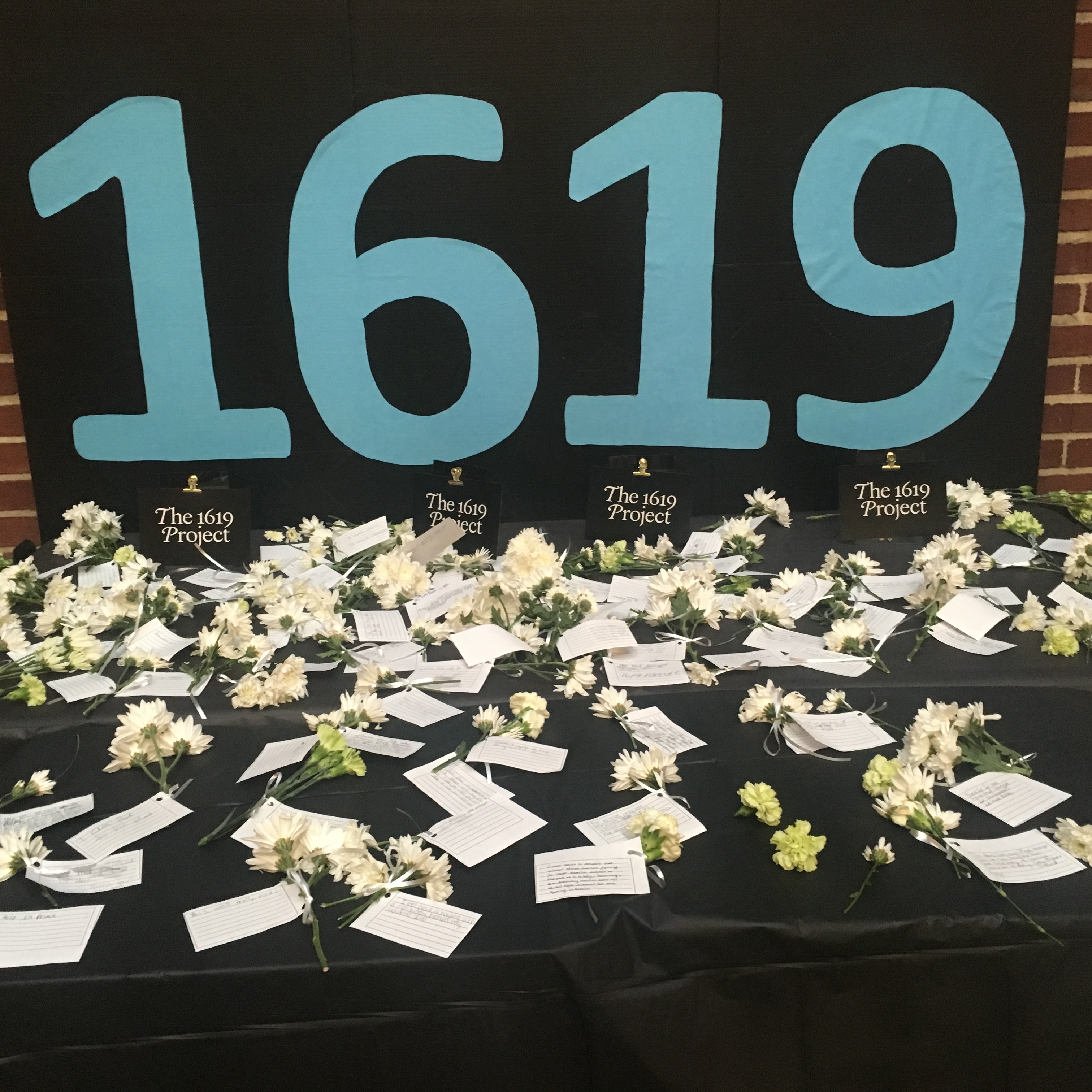

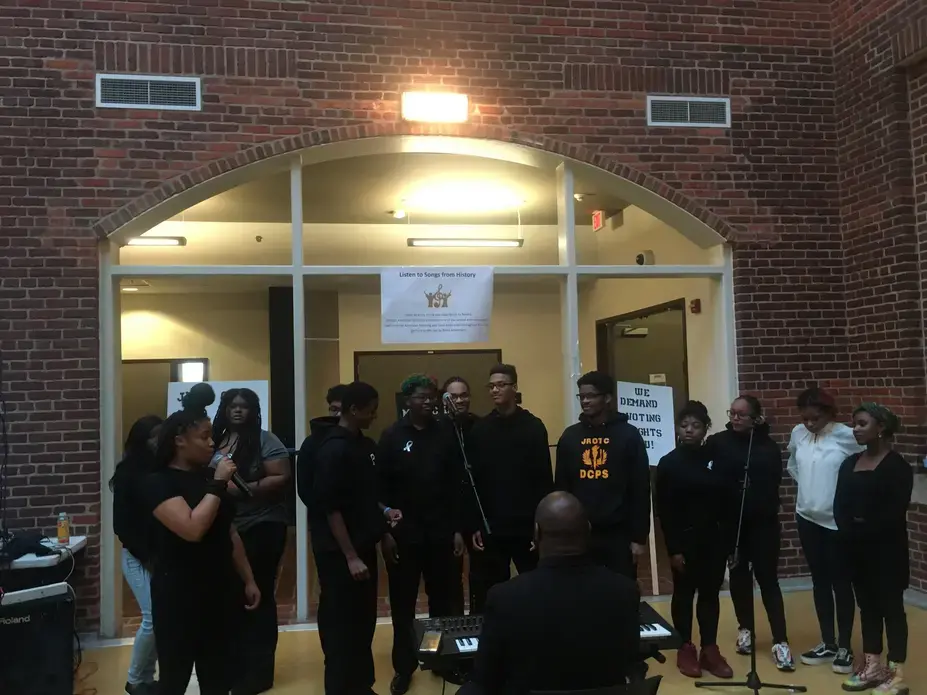

In the darkened atrium, the sounds of a choir rise. Eastern High School students in Washington D.C., dressed in black, are singing a gospel song, printed annotated lyrics beside them explaining the historical importance of African American music. In another corner of the room, attendees are invited to fill out family trees, explore a gallery of poetry by black writers, and speak with performers representing African American innovators throughout U.S. history. In another, they write their personal reactions to The 1619 Project and tie them to flowers. The notes are collected together on a table, a memorial of sorts.

One of them reads: “I feel angry because it took 200 years to end it.” Another: “I want the world to see, recognize, and acknowledge the accomplishments of black America to the US.”

This is a living museum inspired by The 1619 Project, an ongoing initiative from The New York Times Magazine that commemorates the 400th anniversary of the beginning of American slavery: The moment that 20 enslaved Africans were first sold to colonists in Point Comfort, Virginia. The project, spearheaded by New York Times Magazine reporter Nikole Hannah-Jones and featuring work by more than 30 writers and artists, launched with a full issue of the magazine that explores the lasting impact of slavery through 18 written essays, 15 creative works, and a photo essay. The project has gone on to include a five-episode podcast, a kids’ section of the print newspaper, and a broadsheet for the print newpaper that includes an article on how slavery is taught in U.S. schools as well as a history of slavery in 15 objects that was curated by the National Museum of African American History and Culture. The Pulitzer Center supported the project as an education partner, providing free reading guides, extension activities, lesson plans and physical copies of the magazine to educators across the country.

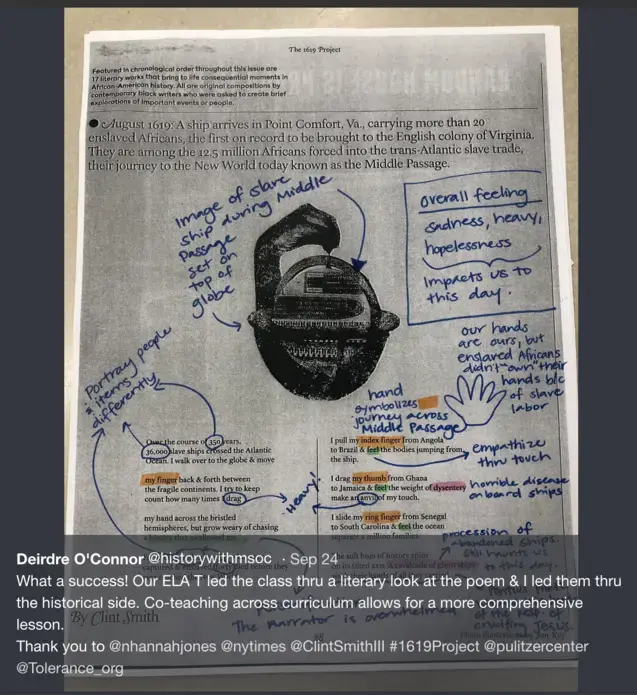

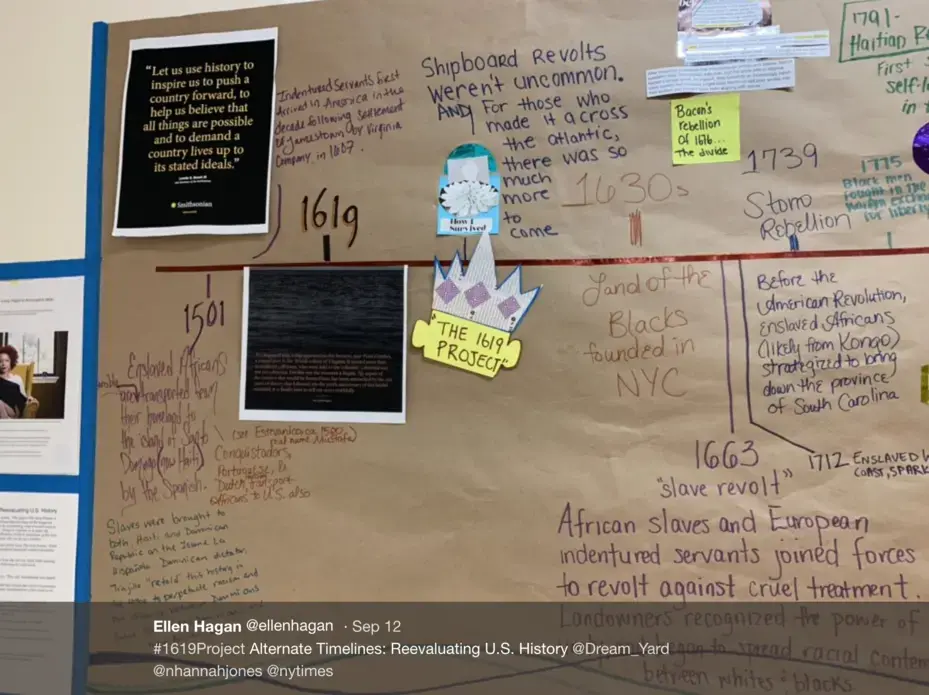

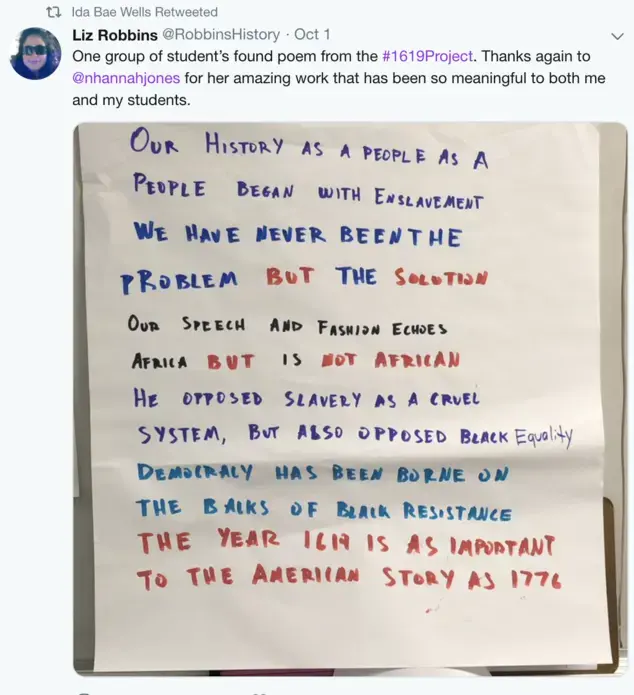

Teachers across all 50 states have accessed the Pulitzer Center educational resources since the project’s launch, and many have shared their students’ work by posting to Twitter and emailing student work to [email protected]. Educators from hundreds of schools and administrators from six school districts have also reached out to the Center for class sets of the magazine. Teachers are using the magazine in their classes to teach subjects ranging from English to History and Social Studies, and their engagement with the project has guided students in creating essays, poetry, visual art, performances, and live events that demonstrate their learning.

A Historical Reframing

In the article “Why Can’t We Teach This?” which was published in the print broadsheet for the The New York Times, reporter Nikita Stewart outlined the history of the teaching of enslavement in schools. “Think about what it would mean for our education system to properly teach students—young children and teenagers—about enslavement, what they would have to learn about our country,” wrote Stewart. “It’s ugly. For generations, we’ve been unwilling to do it.”

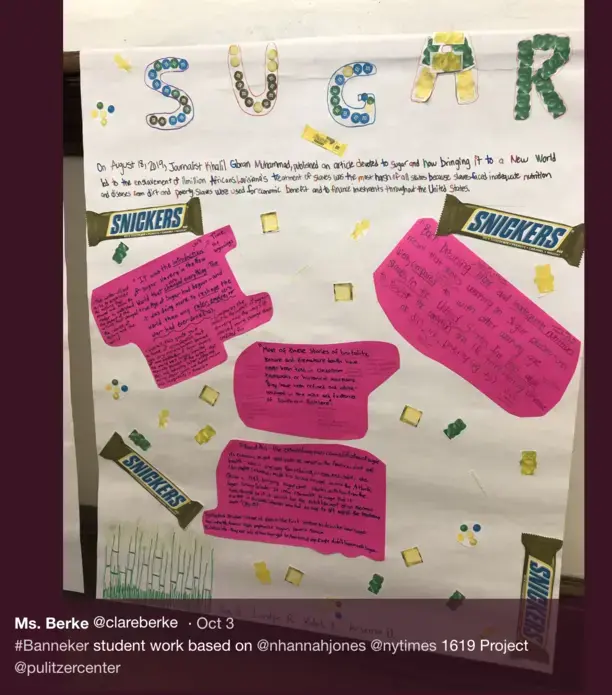

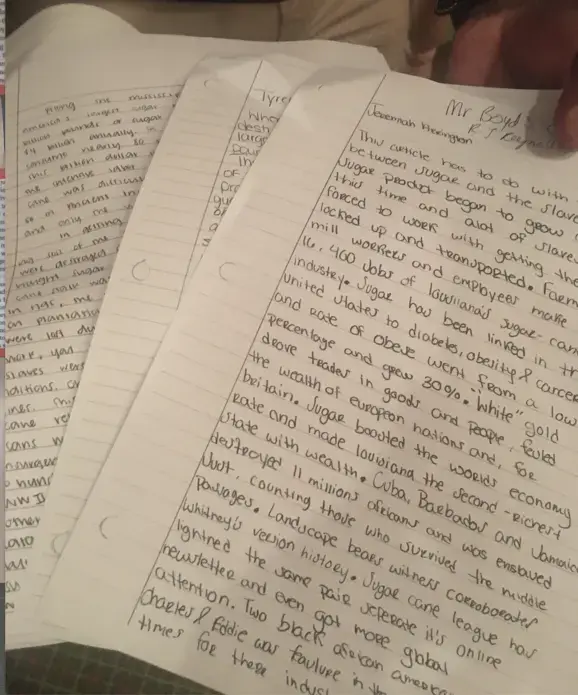

The 1619 Project tackles the subject of enslavement in a way that will be new to many American students. Scholars, reporters, and poets examine the legacy of slavery as it manifests in our present day, from the brutality of U.S. capitalism to the spread of sugar in diets around the world. Teachers who have received copies of the magazine from the Pulitzer Center reported in follow-up emails that the project has supported and enriched their assigned curricula.

Rebecca Milner, a history teacher at Eastern High School, now uses Nikole Hannah-Jones’s “The Idea of America” as an introductory text in her U.S. history class. Some of her 11th grade students took the initiative to create the 1619 Project Day at their school after using the materials in class.

“We think it’s really, really important to educate our students and our surrounding neighbors about what happened here,” said Navea Edwards, a student at Eastern who helped organize the day-long event. “It’s important to educate people because education stops hate.”

Donna Neary, who teaches at Iroquois High School in Louisville, KY, says that her students were especially intrigued by the images in The 1619 Project’s supplemental broadsheet section. Neary teaches an accelerated program for recently arrived immigrants and refugees. Many of them struggle to read English, but she thought it was critical to have them engage in The 1619 Project.

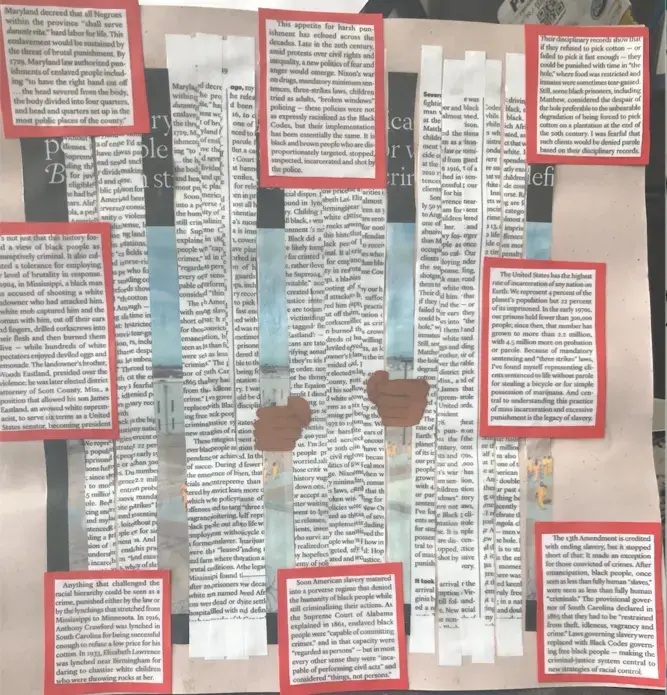

“They jumped right in,” she says, noting that many were “captivated” by the combination of text and images. They began by analyzing the images, which were selected by Mary Elliott, curator with the National Museum of African American History and Culture. Many were transfixed by a photograph from the museum’s collection of shackles used on children. Others were intrigued by the image of Mum Bett, a formerly enslaved woman who sued for her freedom in Massachusetts after her husband died fighting in the Revolutionary War.

She then asked students to reflect on why all Americans should know the information they learned from the project. “I think Americans should know about this because this is how unfair their ancestors treated slaves,” wrote one student. “America must know about the beginning of slavery because they used our backs to create what they call now the United States,” wrote another.

Even for teachers, a lot of the material presents new information. “The information that I am teaching my scholars through this magazine was first learned by me when this was published,” LaQuisha Hall told the Pulitzer Center via email. She has been teaching literacy in Baltimore City Public Schools for 17 years. “I was angry that I didn’t have the opportunity to learn these truths in school,” she said. “I am determined to ensure that not only my current high school scholars have the opportunity but that they have enough to take with them to pass down to their own families and future children.”

Making Curricular Connections

The sheer volume of material encompassed in The 1619 Project—which touches on subjects ranging from healthcare to traffic to music—can be daunting. In this regard, some teachers say the Pulitzer Center materials, including a reading guide featuring key terms and quotes for every article, are helpful.

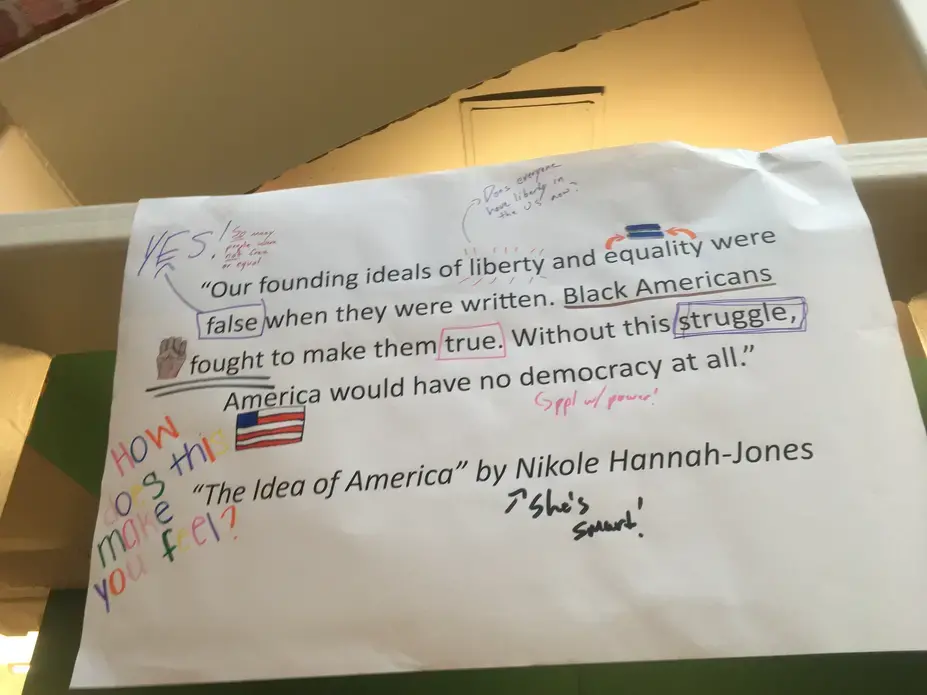

“There’s so much to the material, it’s so rich,” says Elaine Kuoch, who teaches African American History at George Washington Carver High School in Philadelphia, PA. She used the Pulitzer Center’s lesson plan on Hannah-Jones’ essay, “The Idea of America,” to introduce the project to the class.

Kuoch remembers her students reacting when they first encountered the essay, which they read aloud as a class. As they approached the final paragraph, audible 'Wow's and other reactions began to build around the room, which was made up of mostly black students.

“I think it was really powerful for them—one, to hear someone’s story about how growing up, they felt disenchanted with the idea of America, and two, how Hannah-Jones communicated that black Americans have really improved our country,” says Kuoch.

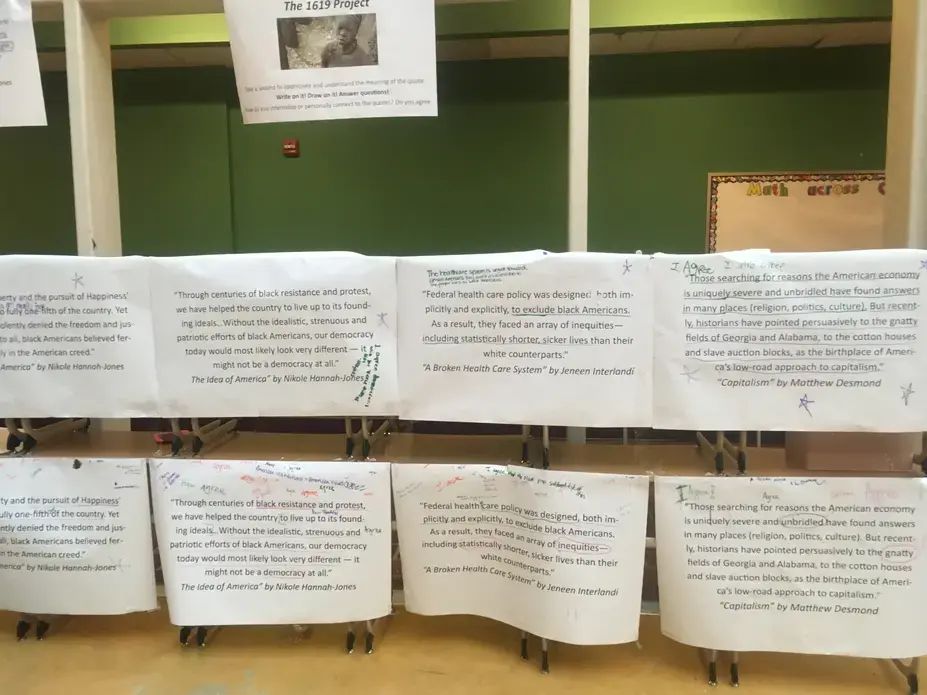

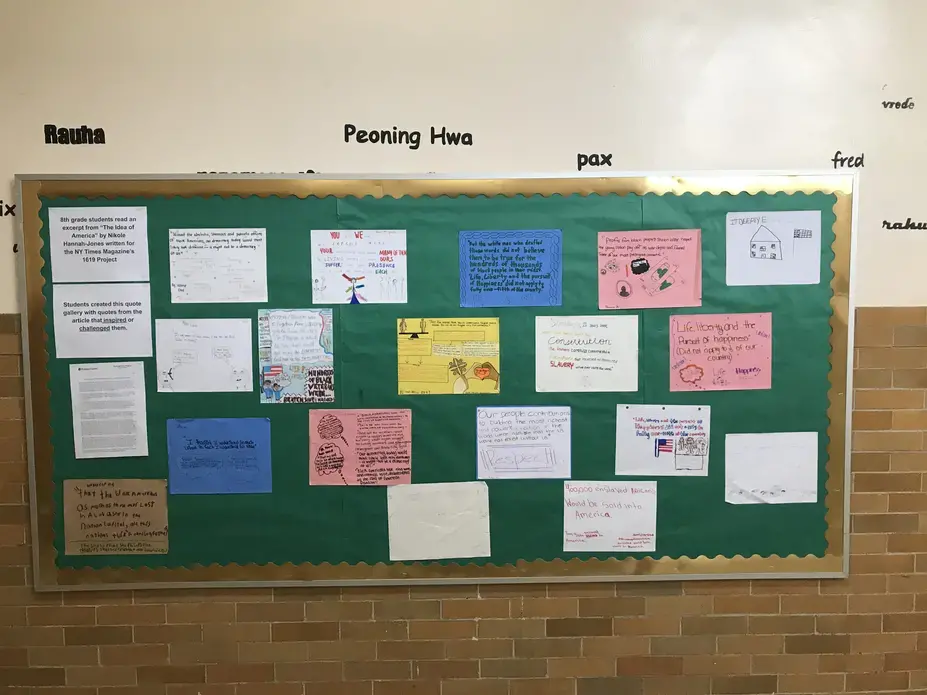

Within a few weeks of the project’s launch in August 2019, educators reported in emails and Twitter posts that their students had tried extension exercises from the Center’s resources to process their explorations of the project. An eighth grade class in Washington, DC created a quote museum inspired by the project’s opening essay from Nikole Hannah-Jones. Other classes created timelines that reflected events highlighted throughout the project.

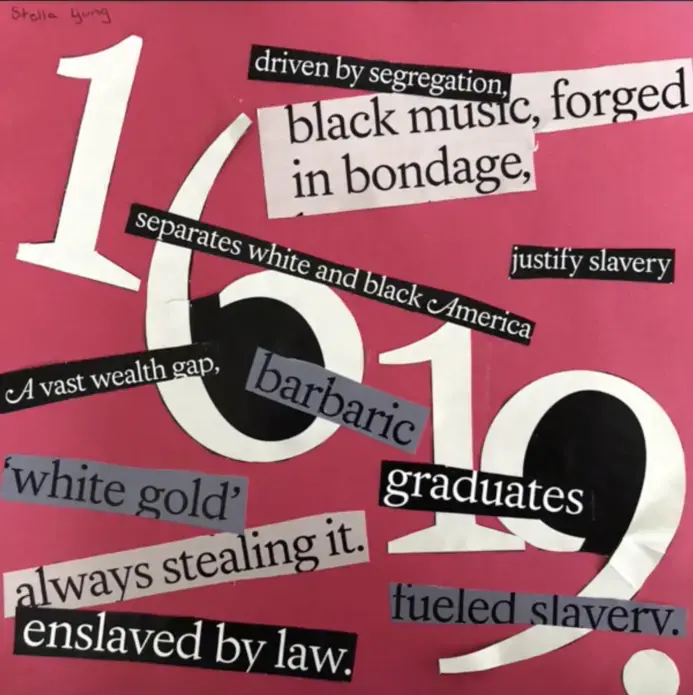

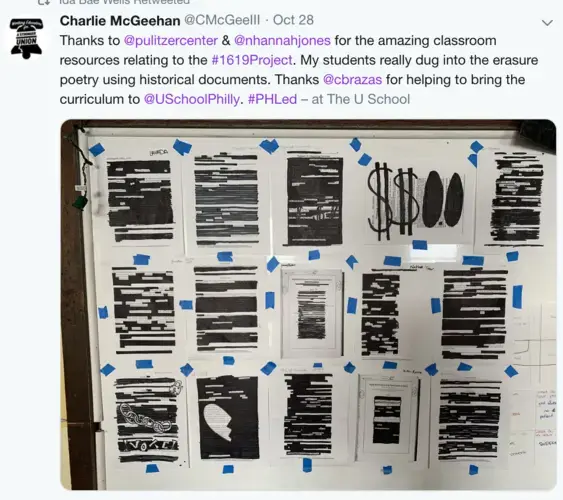

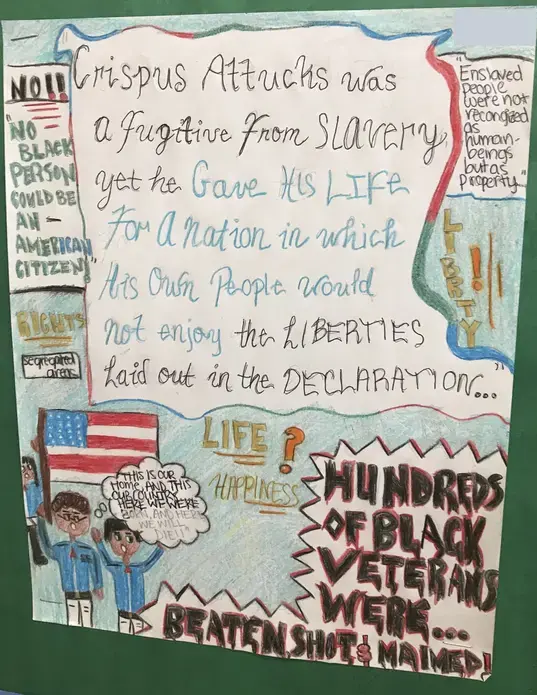

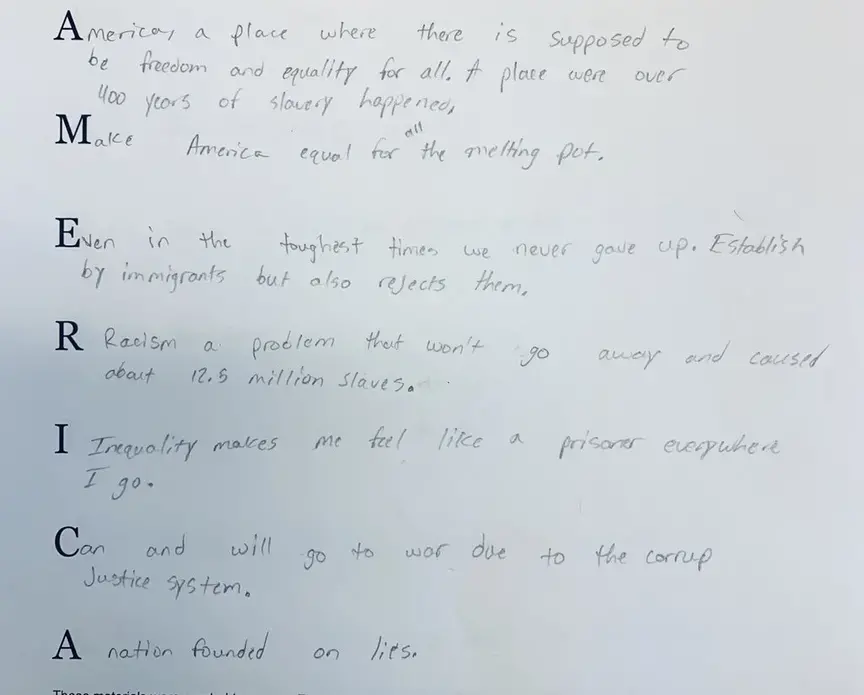

Several educators were drawn to extension activities that guided students in using the project’s essays and creative works to inspire their own original creative writing and art. Charlie McGeehan, who teaches humanities and literature side by side at Philadelphia’s U School, used the creative pieces in the project to discuss the question of American identity from a literary perspective. He then moved to the Pulitzer Center’s erasure poetry activity, inspired by Reginald Dwayne Betts’ piece that used the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793. The activity prompts students to select certain words from historical texts as anchors for original poems that highlight inequity or envision liberation.

“Often reading straight history doesn’t get us deep into emotion and perspective and feeling,” says McGeehan. “There’s not a lot of of textbook resources that put history and literature beside each other in a way that is actually engaging.”

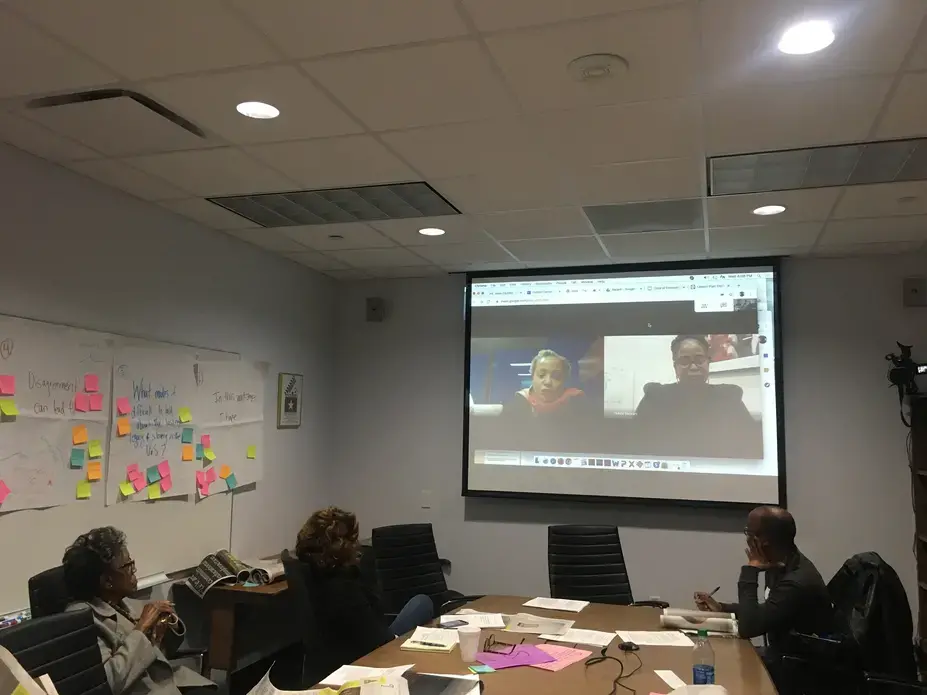

Many teachers have developed their own curricula to support students’ engagement with the project. English and history teachers at R.J. Reynolds High School in Winston-Salem, NC, devised visual art projects in response to the project. A food science class at the same school wrote personal reflections in response to Khalil Gibran Muhammad’s essay on sugar. At Howard University, English lecturer Yael Kiken developed a research assignment using The 1619 Project as a primary source. As part of a professional development workshop for educators in Schenectady, NY, Lori Beza developed a “Quote Mingle” exercise that used quotes from the project as part of an icebreaker for teachers. The exercise has been adapted by Center staff for workshops in Washington, D.C., and Houston, TX.

In addition to guiding students in devising poetry, McGeehan introduced new material to his syllabus after a student came up to him on Indigenous People’s Day and raised the concern that they were not including Indigenous experience in their discussion of US history and American identity. They did an extension after The 1619 Project looking at several other sources, including Roxanne Dunbar Ortiz’s An Indigenous People’s History of the United States. “There was a lot of rich conversation about all those experiences and how what The 1619 Project talks about with slavery connects to land and settler colonialism in An Indigenous People’s History of the United States,” McGeehan said.

The Pulitzer Center is continuing to reach out to teachers for support in gathering lesson plans and activities that they have used in the classroom, and will share those activities as they are posted to the following link: www.pulitzercenter.org/1619

Beyond the Classroom

Across the country, schools, non-profits, and other organizations have planned events to carry the conversation started by The 1619 Project beyond the classroom. Some notable examples include:

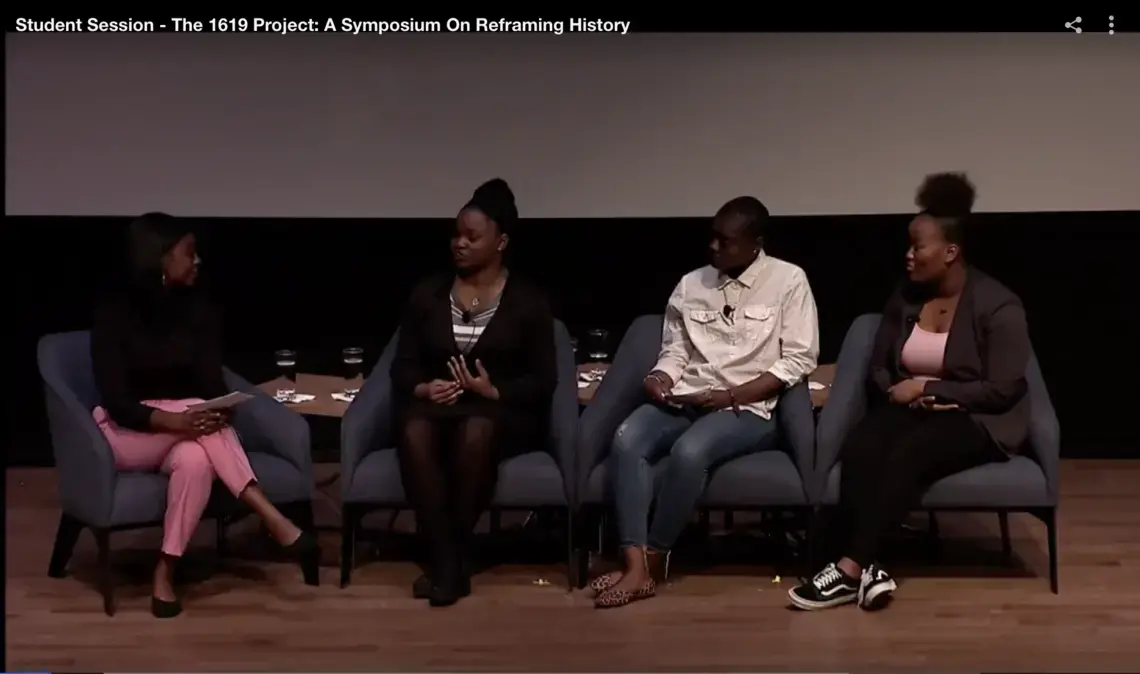

- A Symposium on Reframing History at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, including a 90-minute presentation for students, in October 2019

- In-person visits by Nikole Hannah-Jones in schools and universities throughout the country, including Chicago, Washington DC, Newark, New York City and more.

- “Hear Every Voice,” an event by the Atlanta Speech School. They also developed related activities for students ranging from preschool to high school and organized an event to honor the 400th anniversary of the first ship to bring enslaved Africans to Jamestown.

- A collaborative workshop at the University in Houston in December 2019 that guided a conversation among professors, genealogists, and community advocates about methods for using The 1619 Project to re-ignite conversations about issues facing communities in Houston.

These events, which will continue into 2020, have been lively opportunities for both teachers and students to engage in the material and showcase their work. At Dunbar High School in Washington, DC, students interviewed Hannah-Jones, asking her about every aspect of her process from how she brought the idea to her editors to how she conceived of the audience for this project.

At one point, the conversation turned to Hannah-Jones’s own education and how she had come to the idea to commemorate the year 1619. A student asked: “At school, was this [year] really a topic, or were they trying to cover it up? Like, did you have to go and find it out for yourself?”

In response, Hannah-Jones described the one Black Studies class she had taken as a high schooler, and the book she read which described the significance of this year, called Before The Mayflower.

“I really started thinking about the year 1619 in high school,” Hannah-Jones said. But a lot of her knowledge since then, she said, came from her own research.

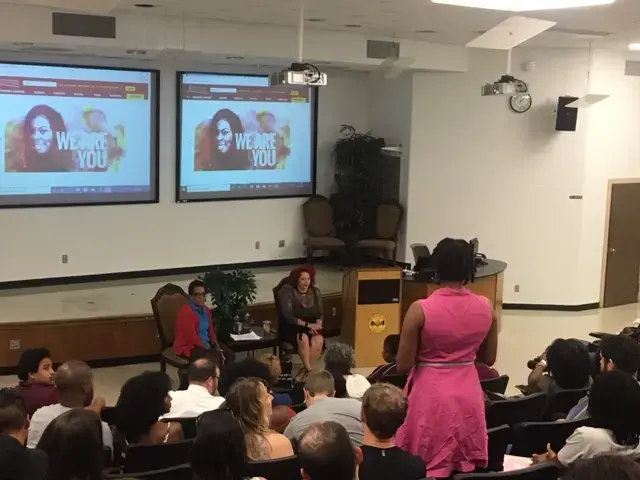

The theme recurred at the Smithsonian event, when Nikita Stewart asked a panel of educators to describe a lie about slavery that they learned as students, and how they unlearned it. As the panelists discussed the issue, several of them encouraged the students in the crowd to do their own learning. They encouraged students to explore the rest of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, to seek out primary source documents, and to start with learning about the history of their own relatives histories at home. There was still a lot of work to be done, they said, but students were already starting to ask more nuanced and difficult questions.

Students will continue to explore those questions in the spring as they access the project in classrooms and through Center-supported events. The Center will also continue to pose student work, and student-designed projects, to pulitzercenter.org/1619 to share their work.

In a student panel at the Smithsonian event, students from New York City and Washington, D.C., described their responses to the project and their experiences creating poetry, visual art and advocacy projects inspired by The 1619 Project.

“I was angry that I hadn’t heard the date before this,” said Christel Robinson, a student at Bard Early College High School in Queens, NY, when asked about her response to the project.

“I thought The 1619 Project was pretty interesting, but I wasn’t surprised by anything in it,” said said Benjamin C. Banneker High School student Stella Makuza.

“I will take what I learned from 1619 and pair with my advocacy and activism work,” Makuza continued. “I don’t feel that I can end how black people are being degraded every single day, but I can join forces with other organizations and my community to demand our respect and get what we deserve.

Robinson said that she was inspired to write a poem in response to a point made in the essay from Nikole Hannah-Jones about the challenges that many black Americans face in tracing their ancestry. ““One of the points that the project was making is that because of the effects of slavery, black families are harder to trace,” she said. “While my white peers could track their families generations and generations, I found that I couldn’t do the same. And even when I could trace it back, it would end suddenly because of a lot of the effects of slavery, and insitituationally racism today that resulted from slavery.”

Below is the closing of Robinson’s poem, which she performed at the Symposium on Reframing History for over 300 DC students and thousands who watched via livestream:

Where is my family?

The last time I saw them was in 1619

My family was stolen, conquered, then on, absent of liberty

But we fought back against it, look all that we’ve achieved

We parted red seas

We used the unmarked graves of our ancestors to plant trees

Imagine my disappointment when all that I can see

Is the desire for equity being laughed at

Any semblance of progression under attack

Everyday struggles to keep the liberty intact

So when you're told to raise your flags

Or stand for the pledge

Listen carefully to the words that are being said

And remember that the perfection of these ideals, for which we have bled

Has yet to be accomplished, no matter how often they have been written or read

Remember that democracy has been caught up, but has yet to get ahead.

For support connecting The 1619 Project to students, or for sharing work created by students in response to the project, contact [email protected].