“American Popular Music” by Wesley Morris (pages 60–67) | Module 1

Module Authors: Melissa Kanoff, Drew Lewis, Rachel May, Sydney Smith, Elias Thompson

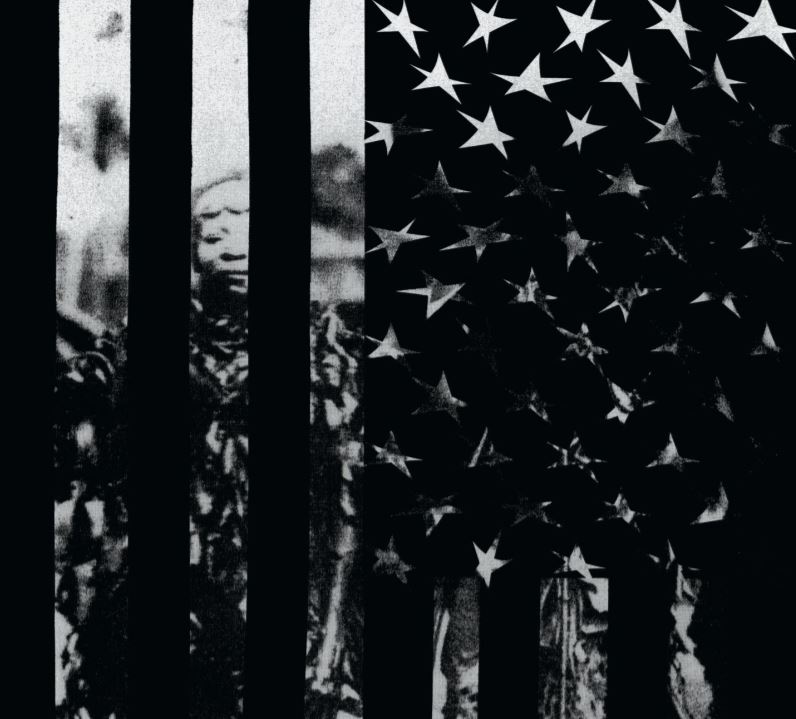

| Excerpt | “It’s proof, too, that American music has been fated to thrive in an elaborate tangle almost from the beginning. Americans have made a political investment in a myth of racial separateness, the idea that art forms can be either ‘white’ or ‘black’ in character when aspects of many are at least both. The purity that separation struggles to maintain? This country’s music is an advertisement for 400 years of the opposite: centuries of ‘amalgamation’ and ‘miscegenation’ as they long ago called it, of all manner of interracial collaboration conducted with dismaying ranges of consent.” “What you’re hearing in black music is a miracle of sound, an experience that can really happen only once — not just melisma, glissandi, the rasp of a sax, breakbeats or sampling but the mood or inspiration from which those moments arise. The attempt to rerecord it seems, if you think about it, like a fool’s errand. You’re not capturing the arrangement of notes, per se. You’re catching the spirit.” |

Key Names, Dates, and Terms |

Black music, cultural appropriation, intellectual property, Thomas Dartmouth “T.D.” Rice, blackface, minstrelsy, Elvis Presley, Lil Nas X |

Guiding Questions |

1. Are Black artists properly acknowledged as being influential, or as original creators of various types of music and media? How has the history of Black artists in American music been silenced or obscured in the past? Is it still silenced or obscured? 2. What impact did blackface and minstrelsy have on music in the early 19th century in the United States? What impact have blackface and minstrelsy of the early 19th century had on the appropriation of Black music in the 21st century? 3. What sort of intellectual property and/or copyright concerns do you think may be brought to light by artists continuously “stealing” Black music? Do you think the legal system is structured to properly compensate Black artists who have had their music “stolen” in this way? If not, how should they be compensated? 4. Are you personally familiar with any examples regarding the appropriation or “theft” of Black music? Which ones? 5. Does the meaning of words change with time? If so, how does that impact American music, for writers and for listeners? |

Additional Resources |

Articles “A Brief Discussion on Intellectual Property for Music Creatives” published by Transcending Sound “A Plagiarism Lawsuit Against Ed Sheeran Depends on One Against Led Zeppelin” by Amy X. Wang “Black Musical Traditions and Copyright Law: Historical Tensions” by Candace G. Hines “Copyright, Culture, & (and) Black Music: A Legacy of Unequal Protection” by K. J. Greene “Intellectual Property at the Intersection of Race and Gender: Lady Sings the Blues” by K.J. Greene “Music and Social Justice” by Tracy Nicholls “Setting the Record Straight on American Music’s Black Roots” by Nastia Voynovskaya “The Roots of Country Music” by Dahleen Glanton Legal Cases: Dixon v. Atlantic Recording Corp., 1985 WL 3049 Williams v. Gaye, 885 F.3d 1150 (2018) Online Resources: “Musical Crossroads: African American Influence on American Music” by Steven Lewis, published by Smithsonian “Musicmap: The Genealogy and History of Popular Music Genres from Origin till Present (1870-2016)” published by Musicmap |

“American Popular Music” by Wesley Morris (pages 60–67 ) | Module 2

Module Authors: Melissa Kanoff, Drew Lewis, Rachel May, Sydney Smith, Elias Thompson

| Excerpt | “It's proof, too, that American music has been fated to thrive in an elaborate tangle almost from the beginning. Americans have made a political investment in a myth of racial separateness, the idea that art forms can be either ‘white’ or ‘black’ in character when aspects of many are at least both.” “The proliferation of black music across the planet — the proliferation, in so many senses, of being black — constitutes a magnificent joke on American racism. It also confirms the attraction that someone like Rice had to that black man grooming the horse. But something about that desire warps and perverts its source, lampoons and cheapens it even in adoration. Loving black culture has never meant loving black people, too. Loving black culture risks loving the life out of it.” |

Key Names, Dates, and Terms |

Segregation, Plessy v. Ferguson, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, country music, Ken Burns, Delvyn Case, jazz, Louis Armstrong, Billie Holiday, The Ink Spots, hip-hop/rap, The Sugarhill Gang, Public Enemy, gentrification, reurbanization, Billboard’s Top 10, Billboard’s “Greatest of All Time Artists,” T.D. Rice, minstrel show, Jim Crow, Dred Scott v. Sandford, The Compromise of 1850, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, the Civil War, Reconstruction, Frederick Douglass, “the slave narrative,” John Brown, Harpers Ferry, cognitive dissonance, Charlie Pride, Emmett Till, the Little Rock Nine, Lil Nas X |

Guiding Questions |

1. What role did minstrel shows play in creating a national ambivalence toward slavery and Black people at a time of racial turmoil from the 1840s to the 1870s? 2. How might the imitation of Black music by non-Black artists demonstrate a distinction between a love of Black culture and a love of Black people? 3. What contradictory attitudes toward Black Americans existed that allowed listening to Nat King Cole on the radio to be popular but caused a television show hosted by the prominent artist to be “too much” for 1950s America? How do these diverging attitudes about race persist in the United States today? 4. Can you identify elements of contemporaneous pop culture that perpetuate ignorance or ambivalence toward the treatment of Black Americans in the United States? 5. How have the politics of racial separateness, i.e. segregation, affected Black Americans’ opportunities to create art? 6. Identify some music types or genres and discuss the elements of their composition. What are the components that make a genre distinct? Are these components severable or an “amalgamation” as discussed in the excerpt? 7. How have the improvisational elements of Black American music shaped American popular music and its historical development? 8. What makes music liberating? Is music’s liberating impact restricted to the dimensions of a song? 9. In what ways is gentrification similar to practices in which non-Black artists profit from Black music? 10. What does this appropriation or desire to “attempt blackness” by non-Black artists do to Black culture and Black music? How does this appropriation influence American popular culture and music? 11. How has the racial segregation and appropriation of music influenced Black culture and the “popular” view of Black music in America? 12. What are some solutions to addressing the problem of harmful imitative exploitation and appropriation of Black music in popular culture? |

Additional Resources |

Articles “Black Musical Traditions and Copyright Law: Historical Tensions” by Candace G. Hines “Setting the Record Straight on American Music’s Black Roots” by Nastia Voynovskaya “The Roots of Country Music” by Dahleen Glanton Online Resources: “Musical Crossroads: African American Influence on American Music” by Steven Lewis, published by Smithsonian Music “Musicmap: The Genealogy and History of Popular Music Genres from Origin till Present (1870-2016)” published by Musicmap |

“Hope” by Djeneba Aduayom (pages 86–93)

Module Author: Ariana Aboulafia

| Medium | Photo Essay |

Guiding Questions |

1. Why is artistic work like this important for law students? 2. Did you find the photographs impactful? Was seeing the photographs of these students more impactful than only reading the text within the essay would have been? 3. Slavery was as much a legal institution as a social and economic one. Do you think law schools should teach the law as a tool that has been historically used for both positive and negative moral outcomes? Does that history and context matter? Why or why not? |

"Law Like Love" by W.H. Auden

Module Author: Ariana Aboulafia

| Medium | Poem |

Guiding Questions |

1. What does W.H. Auden think the law is or should be? 2. In your opinion, what is the law? What should it be? |

You can find this and more educational resources at www.pulitzercenter.org/1619.

The 1619 Project Law School Initiative is a partnership of the Pulitzer Center, Howard University School of Law, and University of Miami School of Law. The initiative is also part of the Racial Justice initiative by the Squire Patton Boggs Foundation and its Deans’ Circle.