LOÍZA, P.R. — A dozen dancers wearing bright, colorful ankle-length skirts gathered around five wooden drums. Their shoulders and hips pulsed with the percussion, an upbeat, African-inspired rhythm.

Loíza, a township founded by formerly enslaved Africans, is one of the many places in Puerto Rico where African-inspired traditions like the bomba dance workshop at the Corporación Piñones se Integra community center thrive.

But that doesn’t mean all of the people who live there would necessarily call themselves black.

More than three-quarters of Puerto Ricans identified as white on the last census, even though much of the population on the island has roots in Africa. That number is down from 80 percent 20 years ago, but activists and demographers say it is still inaccurate and they are working to get more Puerto Ricans of African descent to identify as black on the next census in an effort to draw attention to the island’s racial disparities.

All residents of Puerto Rico can select “Yes, Puerto Rican” on the census to indicate their Hispanic origin. But when it comes to race, residents must choose among “white,” “black,” “American Indian,” multiple options for Asian heritage, or they can write something in. Most Puerto Ricans choose “white.”

But the Trump administration’s slow response after Hurricane Maria and other natural disasters has made many Puerto Ricans reconsider their decision to identify as white Americans, said Kimberly Figueroa Calderón, a member of Colectivo Ilé, a coalition of Puerto Rican educators and organizers who are campaigning for more Puerto Ricans to identify as black on the 2020 census. “We are not the ‘citizens’ that we think we are,” she said.

After Hurricane Maria, Maricruz Rivera-Clemente, the founder of Corporación Piñones se Integra, said it took longer for electricity to be restored in Loíza than in the capital, San Juan, and other parts of the island. “We have the same electrical connection, the same electrical source as Isla Verde,” Ms. Rivera-Clemente said, referring to a popular tourist area in San Juan. “We had no electricity until two months later.”

Bárbara I. Abadía-Rexach, a sociology professor at the University of Puerto Rico and a member of Colectivo Ilé, was shocked when she learned how many Puerto Ricans identified as white on the last census. “How do I fit into a country where I am a minority?” said Dr. Abadía-Rexach, who was born on the island and identifies as a black woman.

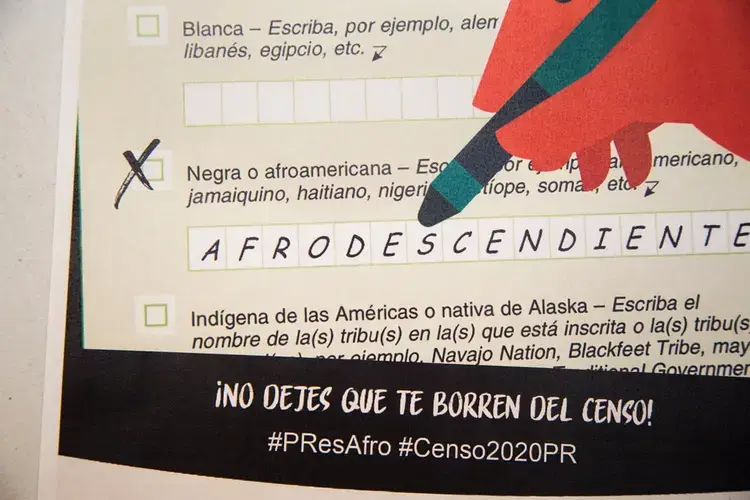

Colectivo Ilé has held educational workshops across the island, teaching residents about the impact of the census and the achievements of Afro-Puerto Ricans, such as the historian Arturo Alfonso Schomburg and the singer Ruth Fernández. They also teach about the contributions of African civilizations, hoping to inspire people to check “black” or write-in “afrodescendiente,” or of African descent, on the census.

“There are people that don’t want to use the word black because they think it’s an insult, and there is still that idea that we need to ‘better the race,’” Dr. Abadía-Rexach said, referring to mejorar la raza, a popular saying in Latin American countries that suggests light skin is more desirable than dark skin.

Many Puerto Ricans say they also feel that choosing black erases their unique cultural identity — including language, food and customs — and aligns their experience too closely with that of African-Americans on the mainland.

“We are clear on the fact that we want to minimize the number of people identifying as white and increase the number of people that identify as black,” added Gloriann Sacha Antonetty-Lebrón, another member of Colectivo Ilé.

Ms. Antonetty-Lebrón said that any shame in identifying as black in Puerto Rico stemmed from a lack of positive or affirming images of blackness. “The education system, which has never talked about all the contributions of black people, has always shown us as slaves and not people who were enslaved,” she said.

But even José Luis Elicier-Pizarro, a native of Loíza and a bomba music teacher at the Corporación Piñones se Integra community center, has reservations about identifying as black. “I don’t say that I’m Afro-Puerto Rican because my father is not African nor is my mother African,” said Mr. Elicier-Pizarro, who has dark brown skin and once wore his hair in dreadlocks.

“For visual reasons, yes, I consider myself black,” he said. “For reasons of identity, I consider myself Puerto Rican.”

Centuries ago, a policy known as gracias al sacar allowed black Puerto Ricans with mixed racial heritage to petition Spain to be reclassified as white for a fee. The practice of reclassifying people’s race continued after the United States seized Puerto Rico in 1898.

Before the 1960s, census takers in the United States and Puerto Rico decided people’s race for them, and applied whiteness liberally on the island, sometimes reclassifying people from black to white. “The Puerto Rican elite was very much working together with the United States and privileging whiteness among the population,” said Mara Loveman, a sociology professor at the University of California, Berkeley. “The unspoken rules of who counts as white were increasingly more generous as part of a broader societal project to appear whiter to the United States.”

According to the Census Information Center at the University of Puerto Rico, census data is used to help determine funding for federal programs based on population. In the wake of political unrest and natural disasters on the island, the data has also helped the government track population declines and the number of residents moving to the mainland. But activists say better census data about race is necessary to understand what some say is a taboo subject in Puerto Rico: racism.

“People say, ‘Well, how can we be racist? We’re Puerto Rican,’” said William Ramírez, the executive director of the A.C.L.U. of Puerto Rico. “It’s been a task to get people to recognize that, yes, there is racism here.” Mr. Ramírez’s office is a 35-minute drive from Loíza, and he said he regularly sees men and women who tell him they have experienced discrimination based on their skin color.

“In Puerto Rico, the language hasn’t been ‘I’m black,’” said Marta Moreno Vega, the founder of the Caribbean Cultural Center African Diaspora Institute in New York City. “The colony never used that narrative. And that’s another part of colonialism: You are labeling people with names that they don’t know.”

Terms like “negra,” “mulatto,” “morena” and “trigueña” represent more common articulations of a person’s skin color, hair texture and facial features that may be used to categorize African descendants in Puerto Rico, Dr. Moreno Vega said, adding that labels can be deceptive. Popular terms like “Afro-Latino” and “Latinx” are useful, she said, but they have limits when it comes to dismantling the legacy of colonialism.

“We have to understand that nothing is siloed,” Dr. Moreno Vega said.

The founders of Colectivo Ilé want their 2020 census efforts to drive social policy for all African descendants, including Dominicans, Haitians and other ethnic groups living in Puerto Rico. Their movement to check “black” is happening alongside other movements to recognize Afro-descendant populations in Latin American countries such as Mexico and Chile.

“The way we measure and identify as black or white will affect how much inequality we see in society along racial lines,” said Dr. Loveman, the Berkeley professor.

“I think it’s a really important symbolic politics to embrace blackness on the census, which is a highly political and politicized space,” she said. “We will get a clearer picture of the state of racial disparities in life outcomes in Puerto Rico.”

For Mr. Elicier-Pizarro, a box on the census is just too limiting to reflect the Puerto Rico he sees as a glorious racial melting pot. In his reality, he is Latino. But more than anything else, he is Puerto Rican.

“That’s who I am. I am a dark-skinned Latino born in Puerto Rico,” he said. “I am Puerto Rican.”