Valerie Nichols lived where she worked, among the residents of Preservation Square whose challenges she knew firsthand through six decades of experience.

Whether it was arranging for the repair of a heater that had stopped working or preparing food bags for those in need, Nichols served the community and asked for little in return.

She could walk to the office until arthritis made life difficult and forced her into retirement in her early 60s. She was the type of worker you didn’t know you needed until she wasn’t there.

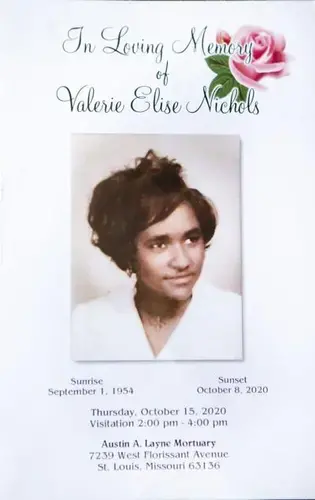

Few people living in the housing development in the Carr Square neighborhood didn’t benefit from her work of 16 years in the maintenance and management office. She remained in her apartment on the property until a sudden illness took her life in October.

“As soon as she gave me an order, I took care of it,” said Charles Roberts, a maintenance worker. “I cared for the tenants as much as she did. She cared about how people lived. If her lights and A.C. and heat were on, she wanted to make sure theirs was on. Just because it was low-income apartments in the hood, it didn’t matter to her. She lived down there all her life.”

Preservation Square is in the city’s 63106 ZIP code, which ranks last in the region in social determinants of health. A landmark regional study showed that life expectancy in 63106 was 67 years for a child born in 2010. Nichols was 66 when she died on Oct. 8.

She lived in the neighborhood where she was raised and gave back until she was physically unable. Her work helped keep residents living in 675 apartments safe.

Nichols’ story was documented in July as she was navigating the challenges of the COVID-19 landscape while doing what she could to monitor her mother, Willie Mae Nichols, who is living at a nursing home in the city.

“She lost her nephew and then her mom became ill, and I think that took a toll on her,” said Nichols’ cousin Debra Wakefield. “It took a toll physically and mentally.”

Longtime friend Marlene Hodges kept an eye on Nichols throughout the pandemic. She helped her with laundry, made welfare calls and brought her a pepperoni pizza and Pepsi on Sept. 1 for her 66th birthday.

“I do know she was tired,” Hodges said. “She had been taking care of her mom, her mom’s house, her bills, her mom’s bills. I would often tell her to take some time off for herself. She was fighting to maintain her mother’s lifestyle and her lifestyle. It took a toll on her.”

Valerie Nichols was her mother’s caregiver for a time. The move to Grand Manor Nursing and Rehabilitation Center came just before residents of nursing homes were sequestered due to the pandemic, making visits few and far between.

Others, such as Roberts, were like members of her family. They met when he started the job in 2010 and quickly developed a close relationship like siblings, he said. Nichols was able to convince Roberts to move into an apartment on the property.

Mica Mosley, who worked with Nichols, saw her develop similar connections with people over the years.

“She knew everybody and was able to relate to the residents because she was one herself,” Mosley said. “They really respected her, and she was sweet to everybody. She knew a lot that was going on because she lived in that community.”

Roberts works with several others handling work orders that Nichols used to distribute. When residents complained that something hadn’t been done, Nichols called Roberts to do the job, even if it wasn’t his originally.

Roberts said Nichols followed up on work herself. She would sometimes visit residents to make sure things were working. She paid special attention to people’s security alarms to make sure they knew their codes and how they worked.

After Roberts was living in the complex, he became susceptible to calls from Nichols at all hours. He once took a call approaching midnight because a woman with three children had lost power on a winter night. They worked with the electric company to get the problem fixed.

Besides arthritis, Nichols had a hip injury from a car accident that made it difficult to get around. She reluctantly retired in 2016. She used a walker and relied on people, including Roberts, to get her places.

She visited her mother this year on a few occasions, and they would talk for about 30 minutes each time, separated by a glass door. In September Nichols called Hodges to say she was having trouble swallowing. Her legs were badly swollen.

“I called an ambulance and got her to the hospital,” Hodges said. “That night they called and said her heart had stopped.”

Nichols was kept alive and placed in a medically induced coma briefly and after that was in and out of consciousness. Hodges visited and talked to her lifelong friend, read to her, sang a few songs and played music. Wakefield, who was baptized with her cousin when they were 4 and 6 years old, also visited.

Hodges, with assistance from Wakefield, made funeral arrangements and cleaned out the apartment. She found nothing out of the ordinary — a lot of photos of family that she gave to Wakefield and a gun and bullets for protection that were turned over to the police.

Nichols’ mother was able to attend the service but believed she was saying goodbye to her younger daughter, who died 20 years ago. “At least I have one daughter left,” someone heard her say, referring to Valerie.

The small service was attended by Nichols’ closest friends, her cousin and Charles Roberts, along with other members of the maintenance and office staff at Preservation Square.

Before Ferguson Beyond Ferguson, a nonprofit racial equity storytelling project, is telling the stories of families in ZIP code 63106 over the course of the pandemic. Sign up to get email notifications and view an archive of other stories at BeforeFergusonBeyondFerguson.com

COVID-19 Update: The connection between local and global issues–the Pulitzer Center's long standing mantra–has, sadly, never been more evident. We are uniquely positioned to serve the journalists, news media organizations, schools, and universities we partner with by continuing to advance our core mission: enabling great journalism and education about underreported and systemic issues that resonate now–and continue to have relevance in times ahead. We believe that this is a moment for decisive action. Learn more about the steps we are taking.