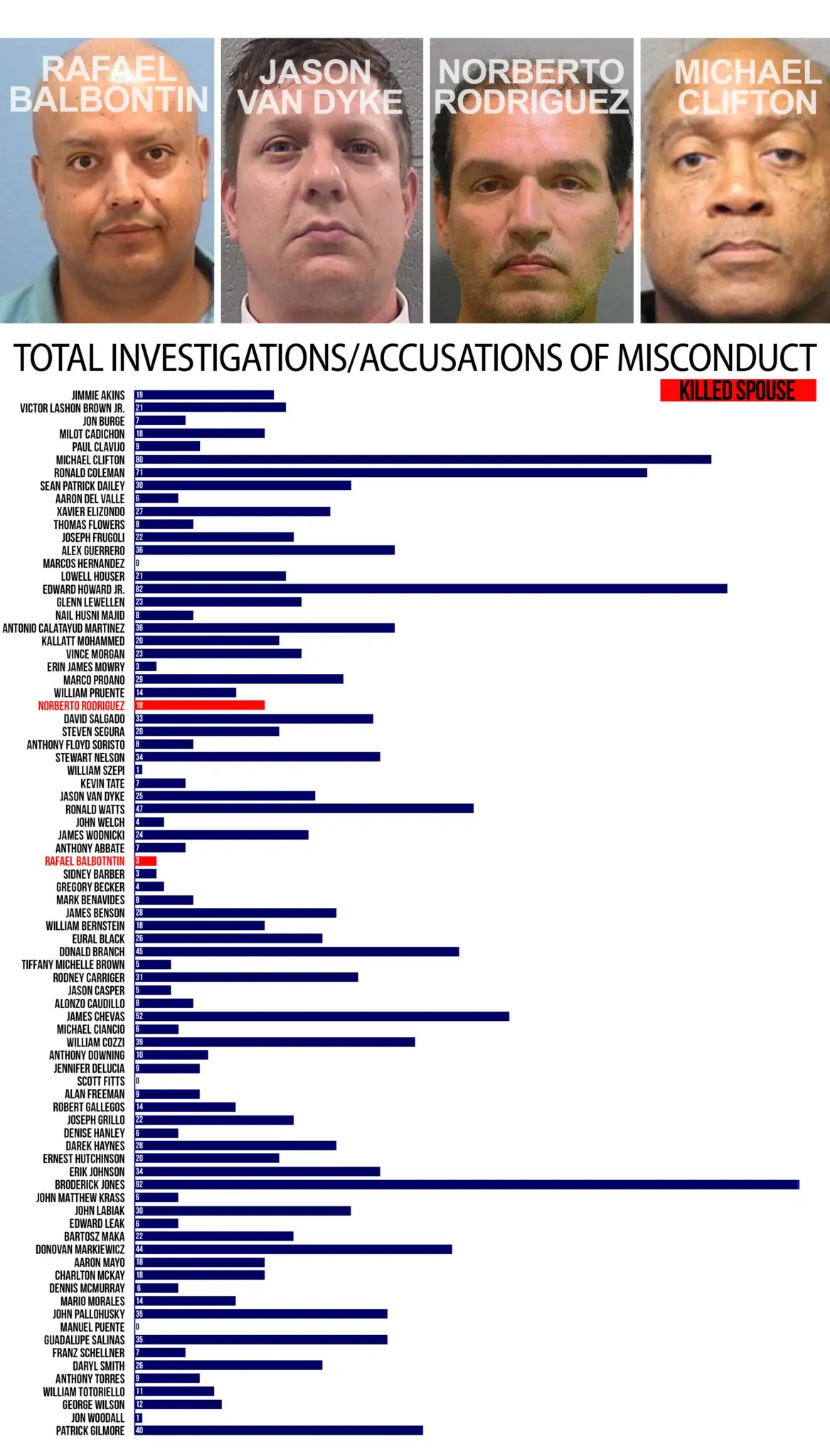

Eighty-one Chicago police officers lost their badges over the past 20 years, but only after being investigated for 1,706 previous offenses – an average of 21 accusations per officer.

One third (28) of these Chicago officers were investigated for domestic altercations or sexual misconduct. Two murdered their wives.

That statistical picture emerges from records obtained by the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting under the Illinois Freedom of Information Act.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund more than 170 reporting projects every year on critical global and local issues. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

The records show that before passage of a new criminal justice reform law earlier this year, Illinois largely failed to hold police accountable for their misconduct over the previous two decades. And even though that new reform law strengthens accountability, a major loophole – buried at the end of the law – closes statewide records of police misconduct. Major media outlets haven’t reported the loophole.

From 2000 to 2020 law enforcement officers in Illinois kept their badges even if they engaged in domestic abuse, sexual harassment, racism, perjury, most misdemeanors and other offenses unbecoming of a police officer.

Over the entire year of 2020, Illinois decertified two officers – one for theft and the other for an offense labeled “other,” an ambiguous category occasionally used in the state’s decertification records.

From Jan. 1, 2000, to Jan. 1, 2021, Illinois decertified 347 officers, an average of fewer than 17 a year.

All told, police accountability measures in Illinois have been no match for a Chicago police force that developed a reputation for brutality from the 1968 Democratic National Convention, to the 1969 killing of Black Panther leader Fred Hampton in a fusicillade of 90 bullets, to the torture of up to 200 suspects by Commander Jon Burge’s homicide squad, to Jason Van Dyke’s murder of Laquan McDonald in 2014. Nor have the laws been a match for Chicago’s powerful police union that has had great success in blocking accountability.

A recent report by the City of Chicago’s Office of the Inspector General confirmed that picture. It found that even when complaints of police misconduct are sustained by the police department, officers are usually able to avoid serious punishment through union arbitration. Settlements often result in violations being expunged from the officers’ records.

Between 2014-17 fewer than a quarter of the 370 officers who contested their discipline in sustained cases of misconduct ended up serving their full suspensions. The rest of the officers who engaged in misconduct – 289 – had their suspensions reduced; more than 100 of them had them reduced by 91-100 percent.

In all 21 cases where an officer made a false report, the sustained charge was removed from the officer’s record after the union negotiated arbitration.

In addition, arbitration is opaque, the IG reported. Arbitration awards are not published. Investigative findings are not disclosed. How discipline changed during arbitration is not disclosed, nor is the arbitrator’s rationale.

On July 21, the City Council took a step toward accountability by passing a new ordinance creating a seven-person commission to increase civilian oversight of the Chicago Police Department by recommending policy changes. Advocates of police accountability say the new process will give activists a prominent platform. But they point out the commission has no authority over discipline decisions on police misconduct.

Below are some of the Chicago abuse cases based on news accounts, court documents, Chicago police disciplinary histories and official records of the Illinois Law Enforcement Training and Standards Board (ILETSB), the state body charged with maintaining high standards of conduct for law enforcement officers. The Chicago Police Department refused to respond to repeated requests for comment.

Jason Van Dyke: Investigated for 25 complaints after 2000. The complaints included searches without warrants, illegal arrests, unnecessary physical contact on duty and excessive use of force. One case led to a $350,000 jury verdict when he used excessive force during a traffic stop involving a Black man who said he was handcuffed so violently that he needed surgery. In addition, a 2013 complaint was categorized as “racial/ethnic.”

Van Dyke still had his badge on October 20, 2014, when he shot and killed McDonald, a Black 17-year-old, firing at him 16 times, hitting him with nine rounds.

Police initially ruled the killing justifiable because Van Dyke said McDonald was facing him with a knife. But a video released under court order a year later showed McDonald walking away. Van Dyke was later charged with first-degree murder and convicted on second-degree murder and sentenced to 6.5 years in prison. His decertification report says he was decertified for a “felony” Nov. 30, 2015.

James Chevas: Investigated for 52 offenses, including 12 “domestic altercations,” and suspended from the department twice.

In 2004, Chevas was investigated for rape/sex offenses, but the final category of these offenses was changed to “miscellaneous” and they were not sustained, according to Chicago Police Department records.

In 2005, just a year after Chevas was first investigated for sex offenses, university lecturer Robin Petrovic accused Chevas of beating her when he was called to assist her after a bouncer hit her on the head with a flashlight at the Funky Buddha Lounge – a nightclub in Chicago where she and her girlfriends gathered to drink lemon drops, court records say.

When officers arrived to help Petrovic, they asked her to sign a blank complaint against her assailant and she refused, according to the Chicago Reporter. When the officers refused to let her provide the narrative portion of her complaint, she asked for their badge numbers and names.

Some officers refused and others gave her the information. She was attempting to leave herself a phone message with the officers’ information, when they attacked her. Here’s the Chicago Reader’s account:

“The officers struck her on the head, threw her against a car and on the ground, hit her and choked her. She was handcuffed and put in a police vehicle, where Officer Chevas threw her onto the ground of the vehicle face first. He began kicking and hitting Petrovic in the head and between her legs, calling her a ‘c---.’ The officers took Petrovic to a police station, refusing Petrovic’s request to go to a hospital for 10 hours. Petrovic was charged with battery, but the charge was later dismissed. As a result of the incident, Petrovic’s eyes were swollen and black, and her body was covered in bruises.”

Petrovic sued and won $261,000 in damages.

Chevas kept his badge after beating Petrovic but resigned from the department after being caught on tape using credit cards stolen from a suspect in police custody. He was sentenced to 30 months probation, according to CNN. The state decertified him for a felony/theft in 2007.

Michael Clifton: Investigated for misconduct 80 times.

In 2006 he was investigated for sexual harassment, and in 2016 groping and forcibly kissing a woman while on duty. He pleaded guilty to a reduced misdemeanor on the 2016 assault charge, according to the Chicago Tribune.

The woman he assaulted had come to the police station seeking a warrant for the arrest of a person who beat her. Clifton, who was working as the warrant officer, asked her to enter his office alone, shut the door and said she “turned him on.” Then he sexually assaulted her, according to the Tribune.

Clifton’s attorney, Timothy Grace, claimed he had an exemplary record. He entered a plea agreement reducing the felony charges to a misdemeanor. He gave up his certification and he spent two years on conditional discharge.

Authorities allowed Clifton to keep his firearms, including his service weapons. The woman he sexually assaulted sued Clifton and the city in federal court and claimed the department ignored patterns of abuse by its officers, according to the Tribune. The city settled just five weeks later and paid the woman $100,000.

The state decertified Clifton in March 2018 for what state records list as “other.”

Norberto Rodriguez: Investigated for misconduct 18 times.

Rodriguez held on to his police license for almost a decade after he went to prison on a 52-month sentence for transporting four kilos of heroin. The state decertification board said Chicago officials failed to notify them of the conviction.

Chicago police investigated Rodriguez for domestic abuse three times during the 1990s and he was suspended or asked to take an unpaid leave for a total of 48 days. In 1992, the department investigated him for assault/battery, an allegation the department sustained.

In 1997 prosecutors charged him with the attempted murder of his wife, Irma, for shooting her in an argument. These charges were dropped, but the department fired him.

In 2001 Irma filed a protective order against him, and also sought protection for her daughter and their son, according to NBC Chicago.

In 2002, a federal judge sentenced Rodriguez to 52 months in prison after he pleaded guilty to possession of heroin when he was charged with transporting four kilos of the drug to Los Angeles, according to NBC. But he kept his police license.

Rodriguez killed his wife, Irma, in 2009, and a jury found him guilty of first-degree murder in 2017.

The Chicago police department fired Rodriguez for domestic abuse/attempted murder and the federal drug conviction, but he kept his law enforcement certification in Illinois until 2011, two years after he murdered his wife, according to state records.

John Keigher, chief legal counsel for the state board, said in an interview it is the duty of the agency and officer to notify the board of a decertifiable offense upon arrest and this is how decertifiable misconduct is usually caught. But he said given how complicated things are in Cook County, it doesn’t surprise him that the city of Chicago or someone else forgot to tell the board about the 2002 drug offense.

“Something like that if it had happened downstate, somewhere where the agency did have a lot more interaction with the board it is more likely that that would have been caught right away,” Keigher said. “We do subscribe to services that inform us whenever there is a news article or something along the line of a […] officer who’s been arrested or prosecuted for something serious. Again in Chicago, I don’t know if that kind of drug felony would even make the papers. It doesn’t excuse it but it just shows our system wasn’t perfect.”

Rafael Balbontin: Investigated for misconduct three times.

Balbontin was decertified in 2007 for a “felony.” Before this, Chicago police investigated him for “murder/manslaughter” in 2005, which the department later changed in its final complaint category to a “domestic altercation,” for which it fired him.

The “domestic altercation” was in 2005 when Balbontin stabbed his wife, Arcelia, to death in her home. He was later convicted of murder and sentenced to 25 years in prison.

This wasn’t the first time Balbontin killed. In 2002 while off duty, he shot 14-year-old Juan Salazar when he broke into Balbontin’s parents’ house with a 26-year-old to steal cologne sold by Balbontin’s father at the local flea market, according to the Chicagoist.

Following Salazar’s death, the Chicago City Council awarded a $2.5 million wrongful death settlement to his family.

Broderick Jones: AKA “Dink” and “Thirsty” was investigated for misconduct 92 times before the state decertified him in 2008 when the FBI discovered he was part of a ring of corrupt cops who were robbing drug dealers. He was investigated the most times out of all the 81 cops in this investigation, but most of these accusations were considered “unsubstantiated” or “not sustained.”

Along with officers Darek Haynes (investigated 28 times) and Eural Black (investigated 26 times), Jones would rob drug dealers they arrested or pulled over on the South Side and extort them for money, weapons and narcotics, according to the FBI and subsequent investigations.

The majority of the offenses were for searches without warrants, unnecessary use of force, displays of their weapons and illegal arrests.

A major reform

The state’s new criminal justice reform law – passed after an all-night legislative session during the January 2021 lame-duck session of the General Assembly – creates a more accountable decertification process, experts agree.

Under the new law, a court conviction is not required for decertification and a broader array of misconduct is decertifiable, including moral turpitude and more misdemeanors. Officers can also be suspended in lieu of decertification or pending an investigation.

Roger Goldman, a Saint Louis University law professor who has studied police decertification for 44 years, said in an interview that the most important part of the new law is the expanded grounds for decertification.

“Most states that decertify don’t require conviction of a felony. They just require commission of an act,” Goldman said.

The fact that an officer can be decertified for committing an act, even if there is no court conviction, and the broad language associated with “moral turpitude” put Illinois in line with most other states, Goldman said.

Background checks required

The new law also implements background checks for officers. Before the new law, the state board assumed no legal responsibility for these background checks and departments often failed to confirm the certification status of the officers they hired.

In response to a FOIA request, the board acknowledged it had no record of a local department requesting the certification status of an officer from 2000 to 2019.

Lya Ramos, FOIA officer for the board, said more recently law enforcement agencies have had the ability to request misconduct information from the Professional Misconduct Database created in Nov. 2019. This database was used 48 times in its first year of operation but never by the Chicago Police Department as of December 2020, according to a FOIA request.

The 2021 law strengthens the board’s Professional Conduct Database. Before it passed, departments were required to notify the board when an officer was fired or resigned under investigation for “willful violation of department policy.” The new law requires additional reporting. It requires departments to also report extended suspensions and actions that would lead to an official investigation for violating a government policy.

In other words, this database contains alleged misconduct that did not lead to decertification, so it is much more comprehensive than a list of officers decertified.

Before the 2021 law passed there was no requirement for a department to check the database. Now there is.

“We have this misconduct database [under the old law], but there [was] no requirement that departments have to use it when they look to even hire someone as part of that background check,” Sen. Elgie Sims (D-Chicago), a sponsor of the new law, said in an interview. “Now you have to look to that database to check if there’s misconduct, or an individual resigned while there was an investigation going on. So those types of things, those updates are necessary, they are long overdue.”

A loophole

But even though the 2021 law expanded the information in the misconduct database and required local departments to check it, a last-minute amendment closed the database to the public and courts.

That loophole is on pg. 669 of the text. It reads: “The database, documents, materials or other information in the possession or control of the Board that are obtained by or disclosed to the Board pursuant to this subsection shall be confidential by law and privileged, shall not be subject to discovery or admissible in evidence in any private civil action.”

Sam Stecklow, a journalist with the Invisible Institute, said this provision in the bill creates a lack of transparency despite court decisions the Invisible Institute won in Illinois saying the public should have access to these records.

A spokeswoman for the attorney general said the reason the statewide database was not open was that the information was available from each police department. But she acknowledged that anyone seeking statewide misconduct data would have to contact the almost 900 departments in the state instead of getting it in one place.

Closing this database on a statewide basis is a blow because it includes the broadest amount of police misconduct information, Stecklow said. He and other reformers are working with the attorney general to eliminate the loophole.

Anti-police?

Attorney General Kwame Raoul rejects the strong law enforcement criticism that the new law is anti-police. He said in an interview that he worked with law enforcement, civil rights and civil liberties groups, to lift law enforcement up and to improve their reputations.

“The vast majority of law enforcement officers certainly try to do their job honorably, they put their lives on the line and their reputation sometimes gets stained not by their acts but acts of some of their fellow officers,” Raoul said. “So we look at this as something that lifts up law enforcement. Lifts up the reputation of law enforcement and takes a step towards restoring some public trust in law enforcement [on] the heels of some of these events that have been seen nationally and internationally for that matter.”

Goldman noted that the law provides a layer of protection for officers by providing hearings.

“In the past there was never a hearing once you were convicted of a felony or one of those misdemeanors that was listed,” Goldman said. “The decertification was automatic. So in this way there is an opportunity for a hearing if the officer wants it and that’s how most other states do it. So that’s a positive too. It gives some due process to the officer that wants to have a hearing.”