On a tranquil afternoon, a light breeze sends little waves lapping along the shores of the island of Vieques. A dog bounces in the shallows. On the sand, a man sleeps in a hammock slung between two uvas de playa trees. Nearby, a few more men lounge in low-slung chairs, drinking beers and playing a slow game of horseshoes.

“You see this?” asks Vieques resident Ismael Guadalupe Ortiz, pointing to a red guesthouse behind the men. It’s illegally constructed, too close to the water, he says. Its recent construction was just one episode in what Guadalupe Ortiz describes as “a vicious fight for access to the island.”

Seven miles off the coast of the main island of Puerto Rico, this guesthouse and beach are in a neighborhood of Vieques known as Bravos de Boston.

In 1941 the Navy arrived on Vieques and over six years took possession of two-thirds of the island’s 55 square miles of land. Thousands of residents were forcibly removed from their land and consolidated in the center of the island, among them Guadalupe Ortiz’s parents.

The Navy phased out of Vieques at the turn of the millennium, pushed by decades of intense local activism and international outcry after David Sanes Rodríguez, a Puerto Rican security guard, was killed in a bombing run — one of thousands conducted by the military over more than 60 years. During that period, the Navy staged training exercises on the beaches of Vieques and dropped thousands of bombs on the land and its surrounding waters — not to mention depleted uranium shells, napalm and Agent Orange.

Almost 20 years after their departure, island leaders are still demanding the Navy clean up buried munitions and toxic pollution, and craft a sustainable development plan meant to bolster the local economy and revitalize long-fallow land.

Many Viequenses fear the island is still not their own. Instead of military occupation, they now face “an invasion of ‘foreign’ capital,” as Guadalupe Ortiz describes it — people from the US mainland buying up property for vacation homes and Airbnbs at prices exponentially higher than what most locals can afford.

As longtime Vieques activist Myrna Veda Pagan Gómez testified June 24 before the United Nations Special Committee on Decolonization, Vieques is experiencing a “tsunami of gentrification.”

The island wasn’t always a vacation destination.

The Navy obliterated the local agricultural economy, leaving Viequenses with few jobs that did not serve the needs of the military. For years, Viequenses struggled to take back some of their land, with rescates, or “rescues,” by occupying unused Navy-owned land and refusing to move, forming settlements like Bravos de Boston in the 1960s and 70s.

It garnered its unusual moniker thanks to the 1948 victory of the underdog Boston Braves in the National League pennant. When locals eventually pushed the Navy out of this small area, seeing a kinship between the scrappy baseball team and their own cause, the Viequenses named the neighborhood in its honor.

Guadalupe Ortiz, a former fisherman and teacher, now 74, was a leader in the long fight to oust the Navy. He now lives on the property given by the US Navy to his parents after his family’s land was expropriated.

And nowadays, Bravos de Boston is an upscale enclave of well-appointed cottages and luxury homes. Streets and houses bear names in English rather than Spanish: North Shore Road, Paradise Cove Suites, Coconut Cay.

An empty beachfront lot might go for as much as $300,000.

A real estate and property management group called the Bravos Boyz caters to outside investors, touting its services as able “help you achieve your revenue goals.” Recent real estate listings show five properties in Bravos de Boston by Bravos Boyz on sale for half a million dollars or more. Bravos Boyz did not respond to requests for an interview.

Like all of Puerto Rico, Vieques has seen an exodus in recent years, both before and after the devastating impact of Hurricane Maria in 2017, which left the island without reliable electricity for 18 months. Since 2010, almost 1,000 Viequenses have left, mostly young people or those with economic means. The current population is estimated at 8,364. Those who remain are disproportionately older and poorer; 36.8% of the population lives below the poverty line, and the median household income is $16,261, compared to $19,343 in Puerto Rico.

Many Viequenses leave because, despite the abundant natural beauty, maintaining a decent quality of life is a challenge. There are few good jobs, little health care and no opportunity for higher education. After the municipal government, the second-biggest employer before Maria was the W Vieques Retreat and Spa. But the storm destroyed the W and it may never reopen. The best-paying jobs remain in munitions cleanup — decommissioning the bombs dropped by the Navy.

But with that work comes risk.

Much of Vieques is still a Superfund site, with unexploded ordnance scattered across thousands of acres on both land and the seafloor and public health consequences that continue to spark debate. Multiple studies conducted between 1999 and 2001 found high levels of radiation and toxic concentrations of heavy metals such as cobalt, cadmium, lead, nickel and manganese in both the “Live Impact Area” of the military-occupied land and on neighboring farms. Today, Vieques’s cancer rate is 27% higher than in the rest of Puerto Rico; rates of cardiovascular disease, diabetes and kidney failure — with which Ismael Guadalupe Ortiz was diagnosed in 2015 — are also high.

Guadalupe Ortiz was lucky; he got a transplant. But other Viequenses with chronic health problems must leave the island for dialysis, chemotherapy and other lifesaving medical treatments — including childbirth. Even before Maria, people traveling to the main island got up at 3 or 4 in the morning to wait for the ferry.

Now, almost two years after the storm, there is still no hospital on Vieques and ferry service has been increasingly erratic and dysfunctional, and the ferry’s main terminal has been moved from the town of Fajardo to a new, more isolated site in Ceiba — on the former Navy base of Roosevelt Roads.

Robert Rabin runs a historical archive and the nonprofit Radio Vieques out of a nineteenth-century fort — a remnant of the Spanish colonial era — in Vieques’ main town, Isabel Segunda. A native of Boston, he moved to Vieques in the 1980s and, with Guadalupe Ortiz, was one of the early leaders of the movement to push out the Navy.

“We have all the negative impacts of colonialism, all the negative impacts of disaster capitalism in the wake of Maria, but there is an ongoing 50-year disaster of militarism in Vieques that creates a different situation,” Rabin says. “It makes [Vieques] supra vulnerable to the forces of speculation, gentrification, displacement and population substitution.”

Thanks to the decades-long occupation, few economic opportunities are available to Viequenses. As a result, outside actors with money — wherever they are from — are able to set their own terms.

“I have a friend [who] says gentrification ... the gringos are taking us out,” says Guadalupe Ortiz, “and I say no, it’s an economic power. ... It’s about rich people, whether they be Puerto Rican or someone else, who are taking us out. It’s not a national problem, it’s a problem of social justice and economics.”

Shortly after the Navy left Vieques, community leaders and planners came together to draft a plan for sustainable development. Updated in 2011, the plan emphasizes preservation of natural resources, ecotourism and small-scale economic development. Tourism infrastructure, it urges, should be centered on locally owned small hotels and guesthouses. This plan remains, hypothetically, the law governing development on Vieques — but for all practical purposes, it seems to be ignored.

“Vieques is the largest holder of public land in Puerto Rico; there is the chance here to do something visionary,” says Kathy Gannett, who came to Vieques in the ‘90s to join the protests against the Navy and has made her home here ever since. But she’s not optimistic.

“After the hurricane, investors are having a field day in Vieques, and in Puerto Rico in general,” she says. “We have unleashed capital on this community.”

Gannett lives in Esperanza, on the south side of the island. This town is smaller than Isabel Segunda, and more tourist-friendly, with a beachfront strip — the Malecón — full of bars, gift shops and higher-end restaurants.

The east end of the Malecón is anchored by a four-story structure of poured concrete: El Blok, a 31-room, adults-only hotel with a rooftop bar. Rooms there start at $140 a night. Driving down the strip, Gannett points out the few businesses that are owned by locals. Some tourist spots look like they’re thriving but one beachside bar, frequented mainly by Viequenses, was essentially destroyed by Maria and hasn’t been rebuilt.

Just west of the Malecón, on a coastal site currently zoned for conservation and agriculture, construction of the $50 million Hotel Zafira St. Clair is slated to start this summer.

Gannett and other activists have been pushing back on the new hotel, pointing out that its scale — 118 planned units, spa, nightclub — are at odds with the Plan for Sustainable Development.

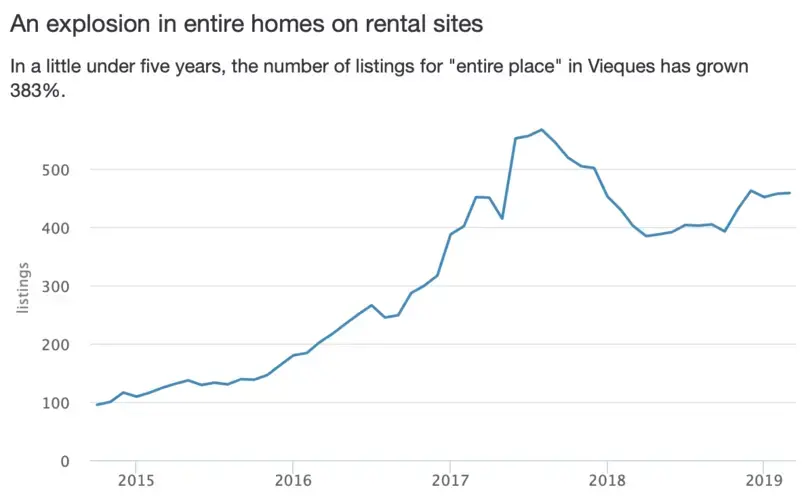

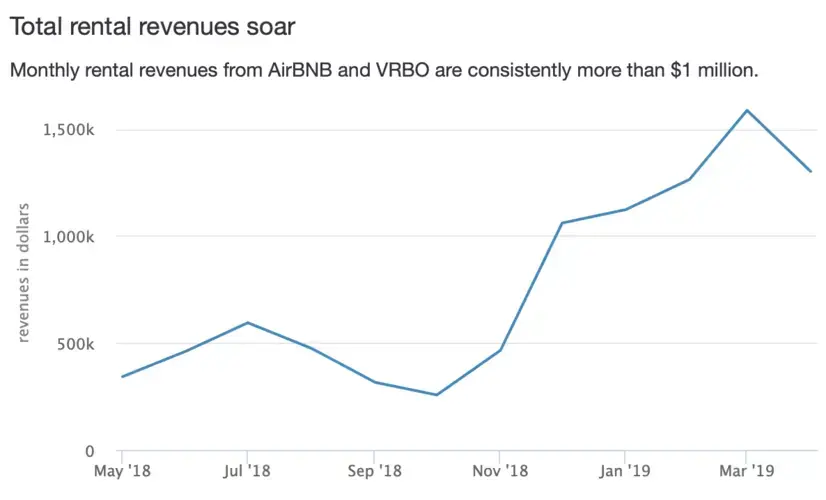

In addition to the mega-hotel boom, close to 500 homes on Vieques are now listed as Airbnbs — the number of Airbnbs renting the “entire place” skyrocketed from 95 in October 2014 to 459 in March 2019, according to data provided by the analytics firm Air DNA. Airbnb locations that had at least one booking for the entire place climbed steadily during that time, from 20 in October 2014 to 389 in March 2019. And the price per night increased from $128 to $266 during that time. In April 2019, total homes rented on Airbnb brought in $1.3 million. The Airbnbs are mainly clustered around Isabel Segunda and Esperanza.

On the main island, some residents rent out their homes or rooms on Airbnb — a lifeline given Puerto Rico’s struggling economy. But on Vieques, many Airbnbs are owned by nonresidents. Locals say that most Viequenses, unable to make a living on the small island, feel pressured to sell their homes to outsiders who then rent them to tourists via vacation-rental websites. Americans from the mainland typically pay prices for property that few Viequenses can afford.

“Displacement here is generally a byproduct of Americans coming and buying up property and Viequenses leaving because they have their older folks in a family and need medical attention or parents concerned about kids not having a good quality of education or quality of life,” says Robert Rabin. “So, in that sense, they’re sort of pushed out.”

“The problem that we have is that many foreigners and people from Puerto Rico come to buy land,” says Zaida Torres Rodríguez, a lifelong Vieques resident and a retired nurse. “Many of the Viequenses sell it to them. Their immediate economic needs are met but they are left without that land.”

This cycle especially affects young people who sell and emigrate to the continental US in order to find work. “But if over there things don’t go well and they come back to Vieques,” says Torres Rodríguez, “they won’t have a place to live because they sold their home.”

And they can’t purchase a new one because the price is now out of their reach.

Victor Emric has served as mayor of Vieques since 2013. Many blame him for the small island’s troubles and say he should do more to make sure tourism benefits locals. But he says there is little he can do to demand more from tourists or Airbnb owners and policies set on the main island dictate most facets of the local economy.

Like many residents, he feels like Vieques is a “colony of a colony” long oppressed by larger forces.

“I was a high school teacher for 32 years, and we were used to hearing bombs go off all the time,” Emric says. “To see how the officers would act at night, drunk, picking fights with Viequenses. I grew up with a rebellion towards the presence of the Navy and what I considered abuse.”

Born and raised in Vieques, and now in his second term, he says the current situation is out of his control. (In 2016 ABRE Puerto Rico gave him a ranking of “D,” and rated Vieques 50th of all the 78 municipios in terms of fiscal health.)

“Many times, development plans don’t reflect reality,” he says. “The reality is that right now, all of PR has a giant economic crisis. People come to Vieques to see its beaches and natural beauty and soak in a paradise island [and] that brings some development in the tourism area but that isn’t enough,” Emric says.

“Vieques generates more than $2 million in room tax but Vieques doesn’t get any of it. It goes to the central government,” he continues. “But the municipality is who picks up the garbage and keeps the area green.”

Owners of Airbnbs were forced to start paying room taxes to Puerto Rico in 2017 — one month before Maria hit. But they are a highly incentivized investment for foreigners. Under Act 22, which offers exemptions on passive income and capital gains for new residents of Puerto Rico, foreign owners of Airbnbs pay no tax. “Home rentals online are the perfect passive investment,” notes a website for foreign investors called Escape Artist. “In the mainland US, people are paying up to 30% of this passive income from Airbnb in taxes. In Puerto Rico, you would pay 0% taxes on passive income.”

Emric does see some benefit in the growing boom of real estate sales and tourism development. “I believe in a balance but we also can’t get to the extreme where we can’t do anything at all,” Emric says. “Who is going to invest, if the North Americans are the ones with money? In Vieques, nobody has capital.”

Emric himself sold the home he and his siblings grew up in. “The Puerto Rican who offered me the most money was $65,000,” he says. “We wound up selling it to a North American from Baltimore at $180,000. I’m sorry, just because somebody is Puerto Rican or Viequense, I’m not going to sell the house for $60,000 when a North American will buy it for $180,000.”

Sylvia de Marco is a Puerto Rican from the main island who now owns a boutique vegetarian ecolodge in the hills of Vieques called Finca Victoria. Before she took over the inn she had been coming to Vieques for years. “I’ve always felt, even as an outsider at the beginning, that it was very strange how the whole island was basically run by Americans,” she says. “It’s a little bit alarming that it’s such a beautiful island but there’s not more of a balance between Puerto Ricans and Americans.”

But, she says, there is little to encourage Puerto Rican and Viequense entrepreneurs to start businesses on the island. “There’s really no incentive, and even when there is, for a small business, you have to fill out all this paperwork and do all this protocol, and it’s so discouraging. Meanwhile, people from the States are coming here and they’re basically giving them everything for free.”

When she was trying to buy a house of her own, she adds, two owners pulled properties from her at the last minute. While she was waiting to get a bank loan approved, she says, “there were Americans behind me with cash in hand. All of these people coming from the outside with more money and more leverage are just really creating a very unbalanced terrain for us.”

Ana Elisa Pérez Quintero helps run Finca Conciencia, a nine-acre agroecological farm and apiary on land recovered from the Navy in an area known as Monte Carmelo.

In the 1990s, she says, her uncle, also a beekeeper, gave bees to the protesters in Monte Carmelo “to use as weapons against the Navy.” Now Monte Carmelo is rapidly gentrifying, and she and her partners have formed a collective dubbed La Colmena Cimarrona — the Maroon Beehive — to found a community land trust, to protect not just the farm but to save surrounding land that might be used to grow food, raise bees and more.

But she worries it may be too late. “We don’t have enough time,” she says. “People are coming in and buying land like crazy. … A lot of residents are getting visits from people with blank checks.” Times are tough, she notes, and if people really need money, “they are likely to sell.”

Most of her Monte Carmelo neighbors are Americans from the mainland now, she says, and for the most part, seem removed from the history and culture of Vieques. They don’t speak Spanish and, she says with a laugh, “They don’t like roosters — so why do you live here?!”

“Vieques was rescued for the Viequenses, so that the people of Vieques could keep living and populate here, not so that outsiders could come,” Torres Rodríguez says. “There are people who live here that don’t know the system of life we’ve lived here. Other residents who weren’t here and have not fought for this land. The idea is to rescue it for our grandchildren, great-grandchildren and great-great-grandchildren so that they have an inheritance. Not so that we could disappear from history.

“In the future, our grandchildren and great-grandchildren will ask us, ''Where am I going to build a house when I grow up?’” Guadalupe Ortiz says. “What are we going to answer to future generations? There are no plans. Vieques needs to be repopulated with Viequenses who have left.”