On a late Wednesday night in June 2020, Lanie Rose was caught in a nightmare: the recent murder of George Floyd. The news traveled all the way from the United States to her home in Bristol, England, and her anger and grief left her unable to sleep.

At 10:00pm, her phone brightened with a call from two of her friends—one of whom was a theater designer. They were planning to paint a mural in support of Black lives the next morning and asked Rose if she would like to join.

She immediately accepted her friends’ invitation. The friends, both white, pitched their ideas to her: blanket statements such as “Black Lives Matter” and “White Silence is Violence.” While the statements were valid, Rose couldn’t help but feel like they could promote a stronger message. This caused her even more sleepless hours.

“I just lay up not being able to sleep because I was thinking of all the different things that maybe the wall could be used to create,” says Rose. “And I came up with an idea: I wanted it specifically to be about highlighting the racism in England.”

“I explained to [my friends] what I wanted to do, and everyone that was there was completely happy to let the project be mine. I drew up a design, and we spent the next two and a half three days creating this thing that I just kind of came up with the night before in my bed.”

The friends could have painted over a random wall in the cover of night like many of Bristol’s greatest graffitists and street artists. Instead, they reserved space on an outdoor gallery wall owned by The People’s Republic of Stokes Croft (PRSC).

PRSC, founded in 2007, is a community-based arts and social justice organization. It runs youth art and activism workshops and sells politically radical books, prints, and hand-decorated china. The proceeds fund programs benefiting Bristol’s low-income and homeless communities as well as the upkeep of its outdoor gallery wall on Jamaica Street.

According to PRSC’s mission statement, it sees “direct action as a means to move things forward, start discussions, and disconnect it from criminality. [PRSC] campaigns for legal graffiti walls and areas …[and aims] to start a discussion, playfully challenge the status quo, and inspire people to find their voice.”

Social justice-themed public art is not a new phenomenon. But recently, unlikely actors are becoming more directly involved. Community-based art groups, businesses, and even government organizations are commissioning and offering spaces for artists to create social justice art on their walls, streets, and parks. This signals a changing attitude toward perceptions of public street art. Many organizations are now embracing the form, the artists, and their possibilities for influencing positive societal change over villainizing them.

According to James Daichendt, art history professor at Point Loma Nazarene University and author of Stay Up! Los Angeles Street Art, there are three main categories of art in public spaces: graffiti, street art, and public art.

While graffiti is illegal, public art is publicly sanctioned and (in some cases) funded. Depending on whether or not the artist asks permission to create his or her work in a public or privately-owned space, street art can be illegal or sanctioned. Definitions of these categories aren’t the clearest. But, generally, as the categories progress from graffiti to public art, the text-based hand lettering evolves into incorporating more pictorial imagery and more formal principles of design.

For example, take the massive, yellow “Black Lives Matter” piece on Washington, D.C.’s Black Lives Matter Plaza Northwest. The piece is entirely text-based. But since the piece lacks pictorial imagery and D.C.’s mayor, Muriel Bowser, commissioned the piece on the street, it falls into the category of street art.

The organization MuralsDC is responsible for this street art and connecting Bowser with the eight local artists who sketched out the design.

Nancee Lyons, the coordinator of MuralsDC, says the project “was founded in 2007 by a former D.C. city councilmember to combat a surge in graffiti.”

The project is part of D.C.’s Department of Public Works. It works as a liaison between artists, businesses, and the communities around D.C. to replace illegal graffiti and tagging with what it hopes will be beautiful artistic murals.

Businesses donate wall space, and the project chooses a lead street artist to work with the business and bring to life his or her idea for a mural. The installations typically occur between August and September, and the city of D.C. pays for the murals.

“[MuralsDC] really embraces a lot of these amazing graffiti artists,” says Rose Jaffe, one of the program’s many affiliated artists. “They hire them to beautify the streets that they might otherwise be tagging and pay them for it. Public and private funding for the arts is great, and I think it’s wonderful when the city steps up and does that.”

On a rainy October afternoon, Jaffe, 32, was organizing art materials in her Washington, D.C., art studio. She just returned from a Home Depot run. The muffled sounds of shifting supplies, running water, and flipping pages can be heard in the background of our phone call.

Jaffe, a native Washingtonian, moved back to D.C. after receiving her bachelor of fine arts degree at the University of Michigan. As a young artist, she found community with a group of street artists in D.C. who created social justice-inspired wheat pastes. Jaffe’s vibrant prints, paintings, illustrations, and posters address everything from climate change and voter registration to racial profiling and immigration reform.

“Art helps push the needle forward,” says Jaffe. “And I think that art, in the form of social justice, is such a powerful way for people to express themselves about what's going on and respond. It's especially important that artists really show up and speak out about any number of topics that are happening right now.”

Some of Jaffe’s favorite public artworks are those in collaboration with businesses and highlight social justice issues. In 2016, she created a mural depicting homeless individuals on the side of the Community for Creative Non-Violence. She also erected a monumental portrait of the late Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg in 2019. Most recently, she created a mural commissioned by the National Women’s Law Center (NWLC).

The mural, Birth Control Way, is located on 909 U Street Northwest. Vibrant blues, yellows, and oranges make up the faces of the people. Multi-colored birth control pills, patches, and IUDs surround them. Underneath runs a dark blue banner with “My freedom, my voice, my birth control, my choice” scripted in teal text.

Jaffe completed the work with the assistance of queer multimedia artist Sed Nah and trans artist Logan McDowell. The mural aims to spread awareness of birth control access, affordability, and freedom to choose the form that works best for each person.

Mara Gandal-Powers, NWLC’s director of birth control access, says, “It was amazing to witness Rose taking our little nugget of an idea and the concepts we wanted Birth Control Way to embody, and turn them into something literally so big. She translated the core values of our work into something beautiful that draws people in, brings them joy, and inspires them to action.”

“Working with Rose shows that there are always creative ways to reach advocacy goals and expand audiences,” says Awo Eni, campaigns and digital strategies manager for NWLC’s Reproductive Rights and Health team.

“Through Birth Control Way, Rose’s audiences are exposed to the birth control advocacy work of NWLC, and our audiences are exposed to the great projects Rose has done around the city. As a national organization, working with a local artist also helps us build a personal relationship to the city we live and work in every day.”

What organizations and businesses have realized is that public art displays aren’t only a way to beautify an area, but they enhance community engagement, promote inclusivity and belonging, and help educate those who pass by.

Many artists, including Oliver Schäfer, 27, from Essen, Germany, say that art displays in public spaces are difficult to ignore, and invite conversations that may not otherwise be readily discussed.

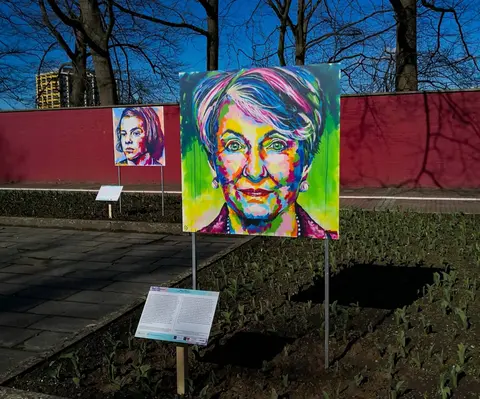

“There was one time when I was just hanging up my portraits and a man came by and asked me, ‘Who did you paint there? Is that your girlfriend?’ I told him, ‘No, this is Anne Frank.’ Remember, I live in Germany. So many people do not know [important] women or their faces.”

Conversations like this fueled his mission to uplift female voices and educate the public through his art.

Schäfer emailed Essen Mayor Thomas Kufen in November 2020. He pitched his idea for displaying his portraits of influential women among the tulip beds of a city-owned park. The city officials loved the idea, he recalls.

Schäfer drew in childhood and started painting when he was a teenager. In 2014, he started a YouTube channel: OlisART. Initially, he uploaded drawing and painting tutorials to inspire other artists. But portraiture really fascinated him. He practiced by sketching models but soon grew bored of their perfect, and often strangely similar, features. Looking for other inspiration, he noticed that many portraitists painted the same, male figures.

He wanted to paint different people. And who were the figures that often inspired him? Women.

“Instead of painting Gandhi or Martin Luther King, Jr. again,” Schäfer says in a WhatsApp message, “I would much rather paint their wives. They were strong women, but we don’t hear or see them enough, and I think it’s not fair.”

Schäfer started his project of painting influential women in 2016. To date, he has completed nearly 20 portraits of female activists, business owners, celebrities, and historical figures. Including research, planning, sketching, and painting, each portrait can take up to two months to complete. He focuses on painting women who advocate for social justice issues, such as environmentalism, sexual assault, racism, and antisemitism.

Beyond the faces depicted in his portraits, there’s more than meets the eye.

“Before I start the painting process, I write down a quote of each person onto the canvas in their mother language. For Greta Thunberg's portrait I wrote it in Swedish, for Anne Frank's portrait in Dutch, and for Marzieh Ebrahimi's portrait in Persian.”

“Once the painting is finished, the viewer is only able to see a few words or letters through the different layers of paint. You cannot read the full quote, and that's exactly the effect I want to create. Because, when I see you in person, I cannot see what's going on behind your forehead. I have to talk to you. I have to get to know you better if I want to know what your thoughts, your dreams, or your fears are.”

Schäfer’s open-air exhibition, Fearless Women, is on display in Essen’s city-owned Grugapark from March 8 to May 9, 2021. The exhibition also features plaques underneath each portrait, written by author and journalist Diana Ringelsiep, with information about the women’s lives and work.

“I hope this way the viewers will look up these women's names, and they will inform themselves about the women I paint,” says Schäfer.

Back in Bristol, Lanie Rose and her friends hoped to spark similar contemplations on Jamaica Street.

The result was a sleek wall of black, white, and yellow featuring powerful quotes and statistics from Black British citizens, news outlets, and government entities about racism in the U.K. During the project, agitated Bristolians reinforced their painted words by shouting racist remarks as they drove past. Nevertheless, Rose was determined to publicly amplify Black voices and experiences through her street art.

Rose posted the completed gallery wall on her personal Instagram and was surprised to receive over 10,000 likes and hundreds of comments and direct messages. As an everyday citizen and event manager recently unemployed at the time due to COVID-19, the attention was overwhelming.

“Just as an individual, and to have all the spotlight at once, no one tells you how to navigate it,” says Rose.

But she found opportunity in what was to be her one-off passion project. Weeks after her first gallery wall, she created her own organization, As A Black Person in the UK, alongside professional artist and childhood friend Ruby Pugh. The organization aims to create street art displays that bring awareness of the Black experience in the U.K. to other British citizens.

Since their first gallery wall on Jamaica Street, As A Black Person in the UK has created two other displays. One was a 60-foot-long rainbow wall along the M32—a motorway between Bristol and South Gloucestershire, England. In another, they painted a black silhouette with a raised fist on a wall in Turbo Park—an undeveloped patch of land at the end of a street corner. As A Black Person in the UK received permission to paint in both of these spaces, thanks, once again, to collaborations between PRSC and the Bristol City Council.

But, as evidenced by a recent report by the Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities, the U.K.’s national government does not seem to agree with As A Black Person in the UK’s platform.

In the foreword of the report, it claims, “Put simply we no longer see a Britain where the system is deliberately rigged against ethnic minorities. The impediments and disparities do exist, they are varied, and ironically very few of them are directly to do with racism … The evidence shows that geography, family influence, socio-economic background, culture and religion have more significant impact on life chances than the existence of racism.”

Rose says the findings of this report are “not only false but gaslighting to all of [her] experiences and work.” It shows there’s much more work to be done and, perhaps, it’s just the inspiration she needs to create her next piece of street art.

“I've definitely had things to say about [systemic racism] before. And no one's ever listened, no one’s ever really cared. Just by creating something bigger scale, and using that creativity, it just instantly is getting people to go, ‘Oh, right,’ and start to educate others and effect change.”