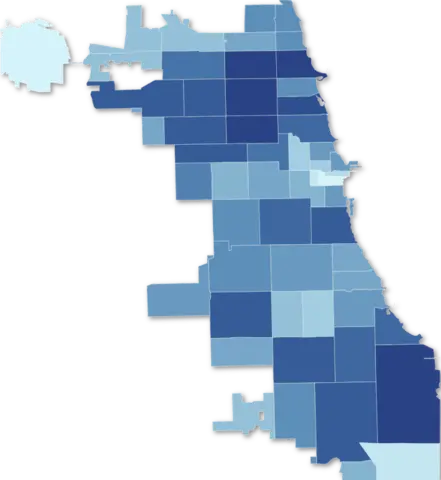

Data Chicago officials recently released showed that the first wave of COVID-19 vaccines administered in the city during December and January mostly went to people living in majority white ZIP codes downtown and on the Near North Side.

But a WBEZ analysis of census data finds that people who likely qualified in the first priority group for vaccines – often called Group 1a – actually live all over the city.

According to data pulled from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, the highest numbers of workers classified as health care and social assistance workers live in several ZIP codes on the North Side, but not near downtown.

The four top ZIP codes for such workers were 60618, 60625, 60640 and 60647. Those areas include much of the Albany Park, Avondale, Irving Park, Lincoln Square, Logan Square, North Center and Uptown communities and smaller portions of other communities. The 60617 ZIP code, which includes all or portions of Avalon Park, Calumet Heights, East Side, Hegewisch, South Chicago and South Deering on the Southeast Side, ranks fifth in such workers.

The analysis suggests that even within the small pool of people eligible to get vaccinated first, those who live in Black and Latino communities were still more hesitant to get shots, despite the fact that their communities have been hit the hardest by the pandemic.

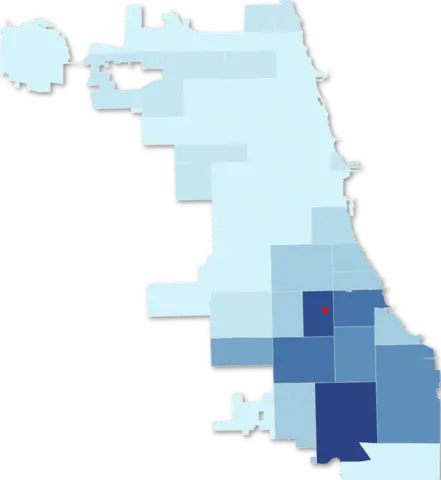

In Chicago, there’s a disparity between where health care workers live and who was initially vaccinated.

*Health care workers, as defined on the U.S. Census Bureau's American Community Survey, include workers in hospitals, ambulatory care services, nursing and residential care facilities, and social assistance services.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau. By: Mary Hall/WBEZ.

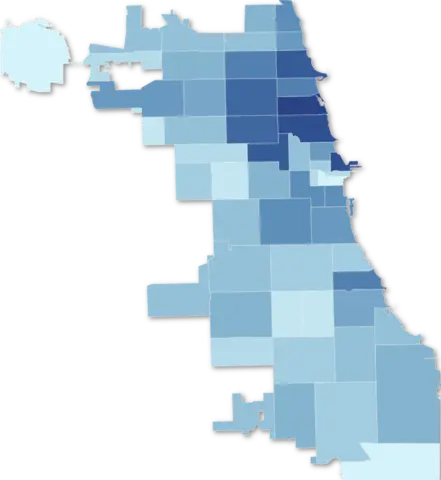

The first signs of such inequities were evident in early January as the city provided data about where people who got vaccinated live.

That data — crystalized in maps the city published online — showed that the bulk of those individuals lived in ZIP codes near downtown or on the North Side.

City health officials say they aimed those first shots toward everyone in the health care community.

“We did not just mean the doctors and the nurses,” Chicago’s Commissioner of Public Health Dr. Allison Arwady said during a Facebook Live in mid-January. “We really felt strongly about including anybody working in these health care settings and hospitals and clinics.”

But when the city released a racial breakdown of the people vaccinated during the first phase on Jan. 25, it showed more than 50% went to white people. National data from the Kaiser Family Foundation indicates about 60% of health care workers are white. On a conference call with reporters that day, Arwady said doctors and nurses “tend to be the highest paid and less likely to be Black and Latinx.”

“Those folks are more likely to live in central Chicago and sort of more in the North Side,” Arwady added. But it was not possible to analyze census data by ZIP code for each job category within the health care and social assistance industry, as that data isn’t readily available.

**People eligible to be vaccinated Dec.-Jan. included health care workers, as well as staff and residents of long-term care facilities, like nursing homes.

Source: City of Chicago Data Portal, 12/15/20 to 1/24/21. By: Mary Hall/WBEZ.

Stark disparities from the start, when major hospitals were primary vaccinators

Overall, the geographic and racial disparities in Chicago were stark, particularly during the first two weeks of vaccinations when they were provided primarily for hospital staff.

During that period — from Dec. 15-27 — 60% of the vaccinations were received by residents of majority-white ZIP codes, while just 12% went to residents of majority-Black ZIP codes and 7% were received by those in majority-Latino ZIP codes, according to the WBEZ analysis.

That was the case at Humboldt Park Health, formerly Norwegian American Hospital, according to Chief Medical Officer Dr. Abha Agrawal.

“In the beginning, 60% of the vaccine doses in the first couple of weeks were all physicians, because other people didn’t want it,” Agrawal said. “Of our physician staff who got the vaccine in the very beginning, hardly anybody lives here in the ZIP code. They do live in the suburbs or in downtown or in the more advantaged ZIP codes.”

Those gaps did narrow as the pool of eligibility opened to include home health workers, nursing home workers and residents, and others. But residents of majority-white ZIP codes near downtown and on the North Side still remain far more likely to have received the vaccine than their counterparts in communities of color in other parts of town.

It’s difficult to pinpoint exactly why this disparity exists. Chicago has not released data showing how much vaccine each facility across the city receives and distributes, nor its underlying data tracking the race of people who receive the vaccine. City officials have also acknowledged those tracking efforts have been hampered, partially by technical glitches and lack of data input from distribution points.

But there is some data that suggest that using hospitals as the primary vehicle to deliver the vaccines may have contributed to the disparities seen in the first few weeks.

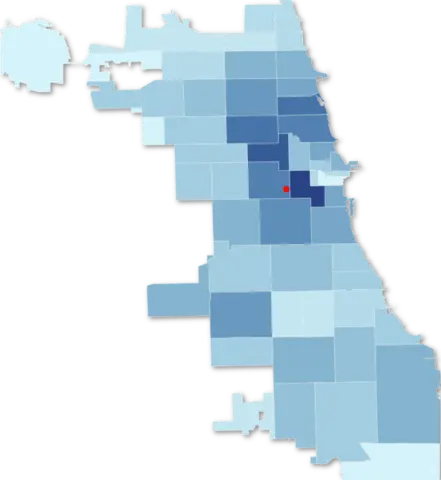

While health care workers live all over the city, those who work in the city’s larger medical institutions — each with thousands of employees — are more likely to live in the neighborhoods that received the most vaccinations during the first two weeks of vaccinations.

WBEZ’s analysis also zoomed in on the specific blocks where hospitals are located to try to understand where people who work on that block live. It is possible that the analysis picked up workers who are not employed at the hospital, but it’s not likely a large number. This block-by-block analysis provides insight into why the hospital-based distribution of early vaccines tipped toward residents of white ZIP codes.

For instance, about 48% of people who work in the census block that includes Northwestern Memorial Hospital lived in majority-white ZIP codes, according to WBEZ’s analysis of 2018 data prepared by the U.S. Census Bureau. The leading home ZIP code for those workers was 60611, located just north of downtown.

And for those working in the census block occupied by Rush University Medical Center, about 43% lived in majority-white ZIP codes. The leading home ZIP code for workers from that location was 60607, located just west of downtown.

From Dec. 15-27, 60607 and 60611 were among the six leading ZIP codes for vaccinations. In each of those ZIP codes — all majority-white and located in or near downtown, Lakeview or Lincoln Park — more than 1,000 residents were vaccinated.

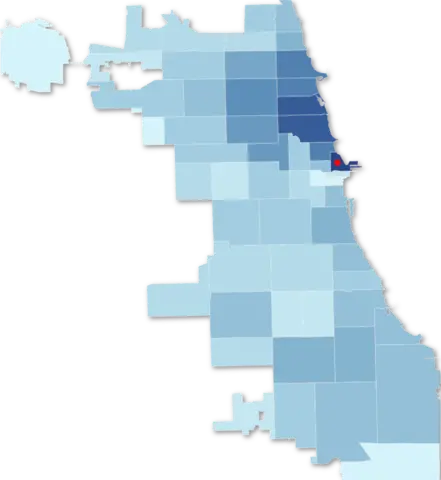

Where health care workers* from four Chicago hospitals live

*Note: Maps reflect the residential ZIP codes of people who work in the census blocks of the main addresses for Rush University Medical Center, Northwestern Memorial Hospital, St. Bernard Hospital and South Shore Hospital. Rush and Northwestern hospitals are larger and employ more people than South Shore and St. Bernard hospitals.

Sources: City of Chicago, U.S. Census Bureau; analyzed by WBEZ. Maps by: Mary Hall/WBEZ.

It was a much different picture for smaller hospitals on the city’s South Side.

Among workers in the census block where South Shore Hospital is located, 80% lived in majority-Black ZIP codes, the analysis showed. The same was true for 72% of workers in the census block occupied by St. Bernard Hospital in the Englewood neighborhood. For workers in each of those South Side locations, fewer than 10% lived in majority-white ZIP codes.

According to WBEZ’s analysis, the leading home ZIP codes for workers of the blocks occupied by South Shore Hospital and St. Bernard Hospital were 60617 and 60628, respectively, where far fewer residents have been vaccinated compared with the home ZIP codes of workers from the blocks for Rush or Northwestern. During the first two weeks of vaccinations, just 202 residents in 60617 received the vaccine, according to the city’s data. In 60628 — which includes all or portions of the Pullman, Riverdale, Roseland, Washington Heights and West Pullman communities — just 111 residents got vaccinated.

Alfred Bolden, chief nurse executive at South Shore Hospital, said initially, a staff survey showed less than 20% of staff were willing to take the vaccine and early inoculation numbers bore that out. But as of last week, nearly 50% of the staff had received at least one dose, according to Bolden.

“Of our physician staff who got the vaccine in the very beginning, hardly anybody lives here in the ZIP code. They do live in the suburbs or in downtown or in the more advantaged ZIP codes.”

— Dr. Abha Agrawal, Chief Medical Officer, Humboldt Park Health

“Seeing friends and colleagues get it and not having bad side effects” helped change minds, Bolden said.

Agrawal at Humboldt Park Health, formerly Norwegian American Hospital, said about 65% of their 1,000 employees have now received at least one dose of the vaccine.

Most staffers at Humboldt Park Health are people of color, Agrawal said, and generally, there was more hesitancy among nurses, respiratory therapists, technicians and secretaries.

But she added, there was one exception: housekeeping staff.

“They came running to get the vaccine,” Agrawal said. “I can’t explain it, but they did.”

A survey of Humboldt Park Health staff who declined the shot found only about a quarter don’t want to get a coronavirus vaccine at all. The remaining three-quarters are planning to or undecided.

Agrawal said she expects Humboldt Park Health will vaccinate between 70% and 80% of employees, which is roughly what the general population will need to reach in order to develop herd immunity.

Equity efforts going forward, but limited supply

City officials hope to reverse the disparities across race and ZIP codes as another 750,000 Chicagoans become eligible. As of now, the vaccine is available to anyone 65 and older, as well as certain frontline essential workers, like grocery store clerks, teachers and public transit workers.

But the limited supply is driving a Hunger Games-like quest for vaccine appointments. Those with more resources and time are more likely to secure the precious few appointments available. And state and local officials have faced criticism that the rollout in Illinois has been too slow, especially when compared to other states.

Alderman Roberto Maldonado, 26th Ward, said it’s not that Latino people in his community don’t want to get vaccinated – it’s that they can’t get access.

“I believe that the majority of us do really want to get vaccinated,” Maldonado said, adding that he knows of just two places in his ward that have been shipped vaccines.

Maldonado said he understands there are limited vaccines available, but the city needs to distribute the doses that are available more equitably, based on need.

Mayor Lori Lightfoot and Chicago’s Commissioner of Public Health, Dr. Allison Arwady, recently announced a plan to target vaccines to 15 communities hit the hardest by the pandemic, including Humboldt Park.

Arwady said outreach is still in the planning stages, but the goal is to not only encourage people to get vaccinated, but provide a direct supply of doses to certain neighborhoods.

COVID-19 Update: The connection between local and global issues–the Pulitzer Center's long standing mantra–has, sadly, never been more evident. We are uniquely positioned to serve the journalists, news media organizations, schools, and universities we partner with by continuing to advance our core mission: enabling great journalism and education about underreported and systemic issues that resonate now–and continue to have relevance in times ahead. We believe that this is a moment for decisive action. Learn more about the steps we are taking.