After Hurricane Katrina, Louisiana officials sought advice from the Dutch.

It makes sense. In the Netherlands, people have been managing water for a thousand years. Coastal communities across the world are now facing new climate threats — rising seas, more intense storms and heavier rain.

The Dutch government goes further than most. Its constitution promises to protect its citizens and the land from threats.

On a November evening in Bellamybuurt, a neighborhood in the north of Amsterdam, people whizz home from work and school on their bikes and mopeds. This is one of the lowest-lying neighborhoods in a city that is on average only about three feet above sea level in a country that’s about 25 percent below sea level. It’s a lot like New Orleans’ Mid City.

Our team took an informal survey — asking passersby whether they worried about flooding in the neighborhood. One young woman out of 10 people answered yes.

You probably wouldn’t hear the same answers from a bunch of New Orleanians. But the Dutch have fewer reasons to worry. Their constitution guarantees “habitability and protection of the environment.” It is a promise the government has made good on with an $8 billion flood protection program.

The Dutch coast hasn’t flooded for decades. That’s largely thanks to infrastructure like the Maeslantkering. Picture two Eiffel towers laid on their sides — the giant white metal arms opening and closing in a big storm, blocking ocean waves and protecting millions of people.

After a major storm killed thousands in 1953, the government built a series of 13 dams, barriers, sluices, locks, dikes and levees called the Delta Works. They were the pride of the nation. Almost every Dutch kid takes a field trip to see the Maeslantkering.

The system has worked well so far. But storms are not the only threat this small coastal nation faces anymore. According to scientists, the North Sea could rise more than three feet by 2100.

Scientists and government officials are modeling for different scenarios. In the best case, sea levels only rise slightly, and continued investment in coastal protection and urban water management keeps the majority of the country safe and secure.

Ferdinand Diermanse is a modeler at Deltares, a water research institute. He says the worst case scenario is that most of the western part of the country is semi-or permanently flooded, and in the future, “there would be protected hubs, probably the cities, where people still live and connect to some roads or maybe transportation over water.”

It could become a nation of islands.

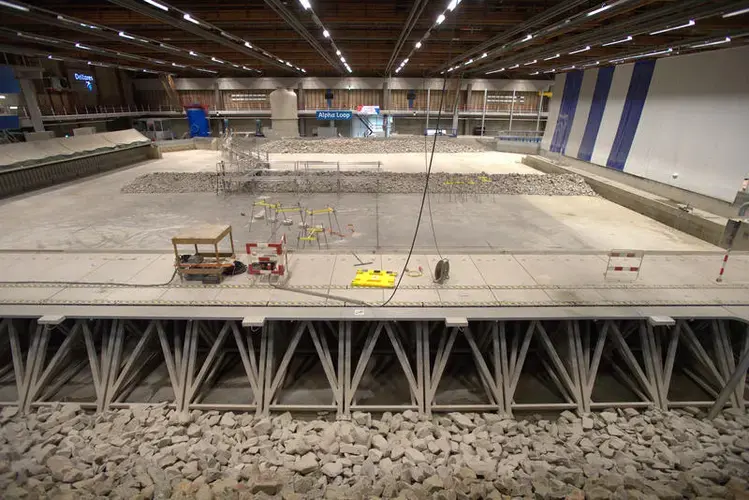

Scientists at Deltares are putting the old infrastructure to the test. They want to find out how it will stand up to these new threats. They have built an enormous “flume” with which they can simulate waves and test out different environments. In one case, they planted a small patch of willow and crashed waves against them and found that the willow roots protected the sandy ground beneath them.

Mark Klein Breteler is a coastal engineer with Deltares. He oversees the flume. On the day we visited he was testing a small rock levee, like those built all over the coast by hand hundreds of years ago. A few still remain, and the local authorities who oversee them have hired Deltares to test how well they will stand up to bigger storms.

Waves smash against the stones, and it starts to fall apart.

“We hoped that the structure would be stronger,” Klein Breteler said. “But the rocks are washing away and tumbling down the structure.” He says local authorities might use this information to reinforce the old rock levees by pouring cement over them to keep the rocks in place, or by removing them and replacing them with something stronger.

Historically, people have felt safe in the Netherlands. But the infrastructure that has worked in the past might not hold up to heavier rain, bigger storms and rising seas to come.

There are a lot of reasons why it is not fair to compare Louisiana and the Netherlands — it’s a small country with high taxes, a more homogenous culture, less rainfall, no tropical storms — but the two places continue to face similar problems of rising seas, subsidence and heavier rains. The Dutch are turning away from walls and levees and exploring new ways to harness the power of nature and live with more water.