In 1981, Martha Brown moved to Charlotte from rural Rutherford County to escape an abusive relationship.

In the nearly 40 years since then, Brown has had more than her share of personal and health misfortunes but always managed to keep herself afloat with a series of low-paying jobs, including as a certified nursing assistant, hotel cleaner and restaurant worker.

Then the coronavirus pandemic came.

It took its toll on the 63-year-old one catastrophe at a time. Over the span of a few months, the virus attacked her health, took away her employment and destabilized her housing. Weeks after recovering, Brown wonders if her life will ever return to its pre-pandemic state.

In early May, Brown was supplementing her disability by working part-time at a small soul food restaurant on the city’s east side. She got sick almost out of nowhere.

“One afternoon, I left work and rode the bus to Walmart. I think I was drooling at the mouth,” she says. “When I got there, I threw up in the bathroom. I went to the emergency room twice and stayed for four to six hours each time. Both times they just sent me back home.”

The details of the next few weeks are a blur. Brown starts to cry as she recounts what she can recall.

“I lost eight pounds because I didn’t eat for 10 days. I stayed in this room for 20 days with my daughter taking care of me. I had a fever of 104 and I could hear them saying they need to break my fever,” she said.

“It was so bad I told God, ‘Just take me home. I’m ready to go home!’ I wanted to die but I said ‘Lord, I can’t leave my only daughter!’”

After a few weeks, Brown’s physical health turned around but by then her job was gone and there was an eviction notice on her apartment door.

Brown’s experiences parallel those of many Black people across the country, state and city whose lives have been upended by the pandemic.

As of November 11, Mecklenburg County has recorded 37,162 cases of coronavirus and 410 deaths. But those numbers only tell part of the story.

A WAVE OF EVICTIONS

Catrice Otengo was one of thousands that had evictions filed against them this summer because of job losses and furloughs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Otengo was interviewed July 31, 2020, in the room she is renting at a local motel. Video by Casey Toth.

State and local governments have offered a patchwork of confusing and insufficient measures to help people like Brown stay in their homes. On March 27, the federal CARES Act imposed a 120-day moratorium on evictions, but it only applied to renters whose landlords had federally backed mortgages.

On May 30, Gov. Roy Cooper issued a statewide executive order that kept residents in their homes by pausing all eviction hearings until June 21. These moratoriums only delayed the inevitable. When they expired, the back rent came due and eviction court proceedings resumed.

In the first week after the state’s eviction moratorium ended, 602 summary ejections or eviction hearings were scheduled in Mecklenburg County and 133 for the week after. Magistrates are working their way through the backlog. Once those orders are issued, says Jesse Hamilton McCoy, a housing lawyer and supervising attorney for the Duke Law Civil Justice Clinic, the time to vacate the residence will come quickly.

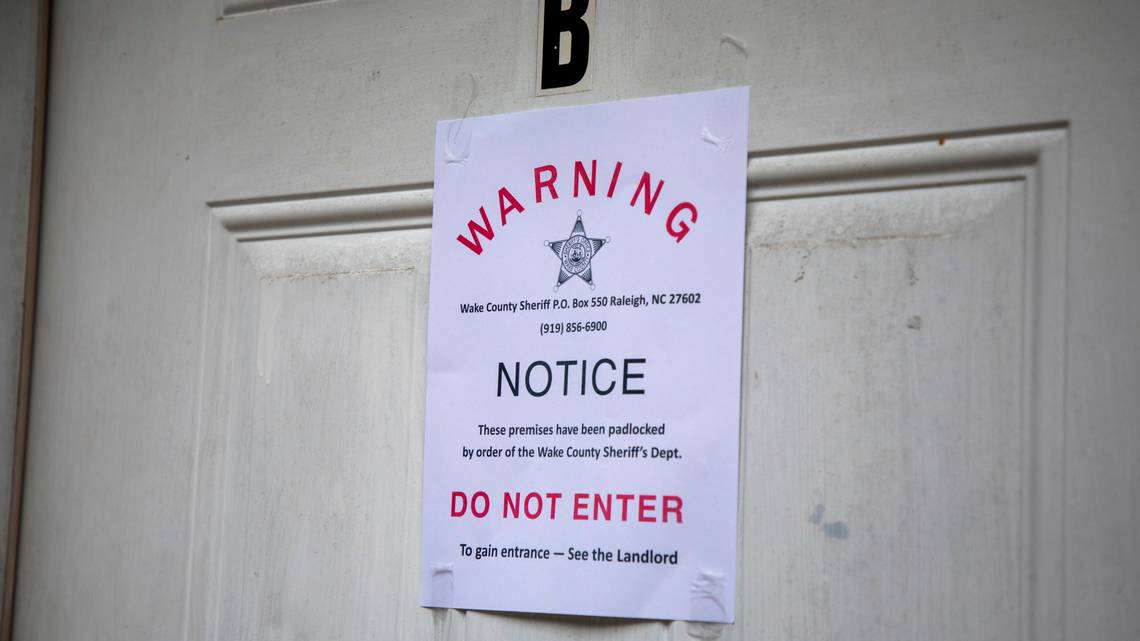

“North Carolina is the second-fastest eviction state in the nation,” says McCoy. “The entire process can be done in as little as 23 days. When the complaint is filed, you get a court date somewhere between seven and 10 days later. If you lose (in court), you have 10 days to appeal and post a rent bond. On the 11th day, the landlord can swear out a writ from the sheriff, the writ gets executed and they can padlock your doors.”

This is the scenario that troubled Brown on a Saturday evening in August as she listened intently to the news. During a press conference, President Trump touted a new executive order that he claimed would prohibit landlords or housing authorities from filing eviction actions, charging nonpayment fees or penalties, or giving notice to vacate.

For a moment, Brown thought that might be the help she’d been praying for.

She soon grew despondent when she realized that the president’s executive order merely directed some regulators to study whether an eviction moratorium was necessary and directed other agencies to investigate whether they could appropriate money for rental assistance.

“What’s this? Is he just saying something for the election?” she asks.

BASIC NEED

Jerome Williams Jr. leads Novant Health’s overall strategy for social responsibility programs, community engagement partnerships, and community impact and wellness programs to address health disparities. He likes to remind you that the pandemic didn’t cause many of these challenges; it merely exposed them.

“Housing insecurity or lack of housing, food insecurity, transportation, lack of access to health care access capital and social capital, lack of upward mobility opportunity to name a few all existed before COVID,” says Williams. “Some of the activities that have occurred prior to COVID are now being exacerbated and I don’t think we’ve seen the worst yet.”

Defined by the World Health Organization as basic necessities that influence how healthy a person or community can become, social determinants of health such as housing, transportation and economic security loom large in the most vulnerable communities.

Social determinants account for roughly 80 percent of someone’s health and chronic medical problems. Housing is one of the most researched and understood of these issues. A number of studies have shown that the chronically homeless and those who are housing insecure are at substantially higher risk of poor health because it can result in disruptions to employment, social networks, education and the receipt of social service benefits.

Even the threat of eviction can negatively impact both mental and physical health. Children raised in unstable housing are more prone to hospitalization, homelessness is linked to delayed childhood development, and mothers in families that lose homes to eviction show higher rates of depression and other health challenges. A 2014 study published in The Lancet found that homeless people have higher rates of premature mortality than the rest of the population.

Williams sees a direct connection between Charlotte’s affordable housing crisis and the disparate impact of the pandemic on people of color.

“We have frontline and essential workers who may not have appropriate or adequate housing or the ability to completely isolate,” says Williams. “A number of them are no longer employed because certain businesses have closed. When paychecks are not coming in, rent can’t be paid. The stimulus isn’t forthcoming so individuals who are already on the margins and already challenged may now be faced with the prospect of eviction, which only exacerbates the problem.”

“YOU CAN’T SHELTER …”

Samuel Gunter, executive director of the North Carolina Housing Coalition, says housing insecurity poses an even greater risk for personal and community health during a pandemic. Government stay-at-home orders presume that residents have a home in which to isolate to avoid spreading or getting infected and to recover.

“You can’t shelter at home if you don’t have a home,” says Gunter.

Brown shares the apartment with her 39-year-old daughter and 20-year-old grandson. Intergenerational living arrangements like this are more common among Asian, Hispanic and Black families, according to an analysis by the Pew Research Center. It also leads to increased patterns of virus transmission because younger people are more apt to go in and out of the house for work or recreation and bring that exposure home to more susceptible family members.

Dense living environments also make effective isolation nearly impossible.

Charlotte and Mecklenburg County have set aside millions of dollars in local and federal funds to provide rental assistance for struggling renters. In addition, agencies like the United Way and Foundation for the Carolinas are raising their own funds to help.

Brown sought help from Crisis Assistance Ministry, a nonprofit that has been providing financial assistance for people in crisis since 1975. It took several weeks for the agency to work through its backlog of requests, but Brown eventually received $1,000 toward her $1,200 rent. But soon, she was back to fretting over where she would find money for the next month.

A COMING TSUNAMI?

On August 7, a group of national housing and eviction experts, including Emily Benfer at Wake Forest University School of Law, released a report, “The COVID-19 Eviction Crisis: An Estimated 30-40 Million People in America are At Risk.” The researchers found that many property owners will also struggle to avoid calamity and face increased risk of foreclosure and bankruptcy.

That stark warning may have pushed the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to issue its September 4 nationwide eviction moratorium for the remainder of the year, a tacit acknowledgment that stable housing and health can’t be decoupled, particularly during a pandemic.

In late October, Gov. Roy Cooper issued an executive order that complements the CDC’s moratorium, increasing some protections for North Carolina renters. His move requires that landlords inform tenants of the CDC moratorium and prohibits them from placing extra hurdles to renters taking advantage of the CDC’s protection.

North Carolina also made available $117 million for the HOPE program, an assistance fund for residents struggling to pay utility bills and rent. But that money has been moving quickly and as of the end of October, more than 22,800 applications had been made for funds.

When there were no state or federal moratoriums in place from June 24 to Sept. 3, Mecklenburg County landlords filed 2,301 eviction cases, according to data analysis by the North Carolina News Collaborative.

A report prepared for the National Council of State Housing Agencies in September estimated that 300,000 to 410,000 households across North Carolina are currently unable to pay rent, leading to the possibility of nearly 240,000 eviction filings in January.

The CDC’s federal eviction moratorium expires Dec. 31. But without additional financial assistance, housing advocates predict another deluge of evictions at the worst time imaginable -- the dead of winter. Cooper’s order expires on the same day.

“You’re just essentially postponing those evictions from now until January,” McCoy said.

For people like Brown, it could be a rough start to the new year.

Melba Newsome is an independent Charlotte journalist who frequently writes about health, education and politics. This story was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center. It is co-published by The Observer, the Charlotte Post and N.C. Health News.

COVID-19 Update: The connection between local and global issues–the Pulitzer Center's long standing mantra–has, sadly, never been more evident. We are uniquely positioned to serve the journalists, news media organizations, schools, and universities we partner with by continuing to advance our core mission: enabling great journalism and education about underreported and systemic issues that resonate now–and continue to have relevance in times ahead. We believe that this is a moment for decisive action. Learn more about the steps we are taking.