In the mountains of southern Ecuador, the future of a Chinese-owned gold mine hangs in the balance. Via the courts, local groups have managed to stop extraction at the Rio Blanco mine. President Lenín Moreno’s government has appealed the ruling.

The story of Rio Blanco reveals the complex problems facing mining in Ecuador: inadequate public consultations; fraught questions of indigenous identities and rights; local versus state power; the protection of scarce natural resources.

Shortly after driving through the beautiful mountains, lakes, and grasslands of Ecuador’s Cajas National Park, Elizabeth Durazno and I reached the first road to the Rio Blanco gold mine. Elizabeth, who hails from the village closest to the mine, frowned at the piece of wood propped up in our path.

She lowered her voice to complain: “We built that road ourselves. Now the mining company is blocking it. We don’t even have the right to use our own road…” She and I stopped by the roadblock and a man emerged from a nearby hut. I’m not sure if he was a mining company employee, but perhaps he recognised her. Without speaking he removed the pole and allowed our car to enter.

She spoke proudly as we travelled up the steep mountain road: “We made our own checkpoint before they did.” The first one was built in May 2018, by the villagers of San Pedro de Yumate on the other road to the gold mine. “Mining company vehicles are not allowed to pass,” the village head had declared.

As you travel higher in the Andes, the climate changes. Rio Blanco, up in the mountains, enjoys cloudless days. San Pedro de Yumate, lower down, has the humidity and precipitation of a rainforest.

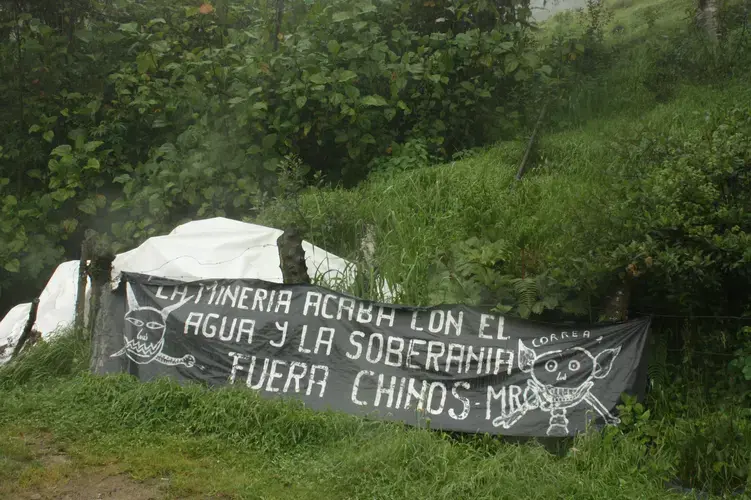

It rained constantly that day in San Pedro de Yumate, with the water gathering in muddy puddles. The original roadblock was still in place, with a guard hut not yet finished beside it. A slogan on a nearby wall could easily have been missed: “Against the terrorist state accomplices of the mining transnationals!”

Another slogan at the entrance to the mountains was more visible, and decorated with a skull: “Mining pollutes water and infringes sovereignty – China out!”

A history of broken promises

As Ecuador is unindustrialised it relies heavily on oil exports and has suffered as prices have fallen in recent years. The country has a 750 kilometre stretch of mostly undeveloped deposits of copper, silver, gold and zinc. Its government hopes mining will improve economic growth. In 2015 mining accounted for 0.42% of its GDP. The government wants that to be 4% by 2021.

Chinese investment has taken a lead role in fulfilling that goal. Three of Ecuador’s five most important mines are funded and operated by Chinese firms. Both the Mirador and San Carlos-Panantza copper mines, in the Amazonian south-east corner of Ecuador, are owned by a joint venture between Tongling Nonferrous Metals Group and the China Railway Construction Corporation. The third is the Rio Blanco gold mine, owned by Hong Kong’s Junefield Mineral Resources and the Hunan Gold Corporation.

Way back in 1993 the British company Rio Tinto-Zinc started prospecting here, before the Canadian firm International Minerals took over. In 2013 Junefield Ecuagoldmining S.A.–the Ecuadorian arm of Junefield Mineral Resources–bought the site and in 2015 it received a license to mine.

According to Junefield’s website, the Rio Blanco project includes four mining concessions covering 5,708 hectares and with an expected lifetime output of 15.7 tonnes of gold and 100 tonnes of silver. Nothing impressive when compared with a major gold mining nation such as Peru, but big enough to be of strategic importance for Ecuador.

In April 2018, 25 years after Rio Blanco locals heard the mountain they lived on contained gold, news broke that Junefield had officially started mining the metal.

Andres Durazno, Elizabeth Durazno’s uncle, is in his fifties and farms trout in a mountain lake. He looked grave as he spoke: “At first, that [British] company told us that life would be easy once there was a mine. But the reality? It’s been over 20 years, has anyone’s life got easier? If you ask me, we’re poorer.”

The road in the village of Rio Blanco is empty. Elizabeth explained that 200 people once lived here, but many had moved to the historic city of Cuenca, 30 kilometres away, where there is work and a high school. Some sold their land to the mining firm before leaving. Elizabeth and her four children now live in Cuenca.

About 20 locals emerge when word gets round a reporter has arrived. Most of them have worked at the mine, as cleaners, cooks, drivers, or labourers. There is little other work here apart from raising fish or farming, and so any opportunity is valuable.

Big mining firms need good community relations to ensure their own operations can run smoothly. The locals say that when the British and Canadian firms were prospecting they sent “sociologists” to speak with them. They received various promises: gifts of sewing machines and cooking equipment, new clinics and roads, investment in agriculture. But “soon after they’d change our contact person and negotiations had to start from scratch.”

The talks stopped altogether when the Chinese arrived, and the number of jobs available fell. Junefield reduced the number of workers and cut hours; currently employees work an average of five days a month, meaning incomes have fallen sharply.

Although drilling for oil started in Ecuador in the 1920s, mining projects run by transnational firms are much more recent. So when teams of foreigners started turning up in Rio Blanco promising to make everyone rich by digging up gold, the villagers weren’t sure what to think.

As Andres said: “We’d never even seen a mine. We thought it would be a good thing.”

They soon realised the foreigners and their machines would bring huge changes but no real benefits.

Andres lists the “crimes” of Junefield: the quiet filling in of a mountain lake; the appropriation of a mountain road in use for generations, with a roadblock preventing locals using it; the storing of mining explosives near a water source.

“We’ve woken up now,” Andres said.

A young villager added: “We haven’t wanted anything to do with the mine since 2017.”

San Pedro de Yumate is a little further away and not directly affected by the mine but opposition has been rising there too. And its location has allowed it to cut off access to the mine.

Village head Chillpi said: “At first we were like lambs obediently following the [Canadian] mining company.” Locals were encouraged to attend a pro-mine demonstration in the capital city of Quito, with travel and accommodation paid for. Everyone was happy to do so but then when they wanted something the company was nowhere to be found.

The villagers also blocked the road, with burning tyres, during the Canadian firm’s tenure. The company’s president arrived from the Ecuadorean capital, Quito, and promised to build an irrigation system, a community centre, and to provide more jobs.

But since Junefield took over, the two villages haven’t had the chance to start negotiations. They’ve never even seen a Chinese person: “They don’t care about what we have to say.”

The two faces of President Rafael Correa

In November 2017, Andres joined a demonstration against the mine in Quito where he met Yaku Sacha Pérez, a Cuenca-based lawyer specialising in water and indigenous peoples. He asked Andres if the government or company had carried out prior consultation with local communities before developing the mine.

“What’s prior consultation? We’d never heard of it before,” Elizabeth recalled.

Prior consultation is a civil right, more fully expressed as the right to free, prior and informed consent (FPIC), included in the 2006 UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

The vast majority of the world’s 400 million indigenous people live in poverty, accounting for 5% of the global population but 15% of the poor. Because of where they live they are often affected by global demand for energy and resources. This led to the idea of FPIC as a prerequisite for any activity that affects their ancestral lands, territories, and natural resources.

But often there is little drive to protect the interests of vulnerable groups, and implementation of FPIC has been difficult in the majority of countries with indigenous populations. This was not the case in Ecuador, thanks to Rafael Correa, president of the country between 2007 and 2017.

While campaigning and in office, Correa advocated for Indigenous people’s rights and sustainable development, and the end of “exploitative capitalism” by mainly American and European investors. Correa declared the country’s US$3.2 billion of foreign debt illegal and refused to pay it back. When U.S. and European firms moved out, Chinese investors moved in. The China Development Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China lent Ecuador US$18.4 billion between 2005 and 2018.

In 2008 Correa called a constitutional convention, at which FPIC and the rights of nature–the belief that all forms of life have the right to exist–were added to the country’s constitution. However, the definition of FPIC in the convention was changed: the requirement for Indigenous people to be informed of plans in good time was retained, but their consent was no longer needed.

Ecuador still doesn’t have the policies to ensure Indigenous people enjoy the right to FPIC. And while Correa benefited politically from promises to protect Amazonian ecosystems and Indigenous rights, he also indicated a wish to exploit natural resources by saying things that run contrary to the spirit of the constitution such as “We cannot be a beggar sitting atop a sack of gold”.

But FPIC has proved powerful in court, especially international courts. In July 2012 the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (set up by the Organisation of American States to rule on whether states have violated an individual’s human rights) found that foreign oil firms had taken over territories belonging to the Indigenous communities in the Sarayaku region of Ecuador without prior consultation.

This was a landmark decision, which gave locals in places like Rio Blanco a precedent to refer to. A key part of that precedent was protecting the FPIC rights of Indigenous people. But in Rio Blanco, the locals had never heard of FPIC rights, and did not actually think of themselves as Indigenous.

Resistance through protest and legal action

Today Rio Blanco is recognised as an Indigenous community by the Federation of Indigenous and Peasant Organisations (FOA) in Azuay province, an organisation for Indigenous people and farmers and part of Ecuador’s Confederation of Peoples of Kichwa Nationality (ECUARUNARI).

There are almost 2.6 million Kichwa in Ecuador, the country’s largest Indigenous ethnic group, spread across the Andes and the Amazon rainforest.

ECUARUNARI works with similar bodies representing Indigenous peoples based in the Amazon and on the coast, via the Confederation of Indigenous People of Ecuador (CONAIE). These bodies bring together Ecuador’s four million indigenous people—25% of the country’s population.

Lauro Sigcha is chair of the FOA. In early 2018, after Rio Blanco locals learned they had the right to be consulted by the mining company, they contacted his organisation.

“The mine’s actually been there for years. The villagers originally had high hopes for it.” Sigcha comes from another village which has protested against mining and is familiar with these struggles. “These villages are forgotten by the government. They get no teachers, no hospitals, no roads. So when foreign mining firms turn up, the villagers hope they will meet these basic needs and provide jobs.”

When jobs didn’t materialise, the villagers started to protest. Sigcha explained: “The villagers found that combining protests with broader social and environmental issues was more effective. So they looked for people with protest experience, and found ourselves and the lawyer, Yaku Sacha.”

Then the villagers’ identity as indigenous people became a factor in the protests.

“My father’s generation would get punished by their parents if they picked up any Kichwa [language]. In Ecuador, being indigenous is nothing to be proud of,” explained Sigcha. The majority of Kichwa people simply describe themselves as farmers.

Indigenous people’s groups have three criteria for designating a community as indigenous: self-identification as indigenous, the indigenous heritage of the locality and communal management of local land.

Several of the common surnames in Rio Blanco are Kichwa, allowing the villagers to self-identify as indigenous. And records in a nearby church proved that Kichwa people had lived here in the past. This allowed the villagers to found their own indigenous group, to make use of FPIC rights and take Junefield to court. On July 23, 2018, Rio Blanco joined the FOA.

That year opposition to the mine by local communities also gained support from anti-mining and environmental activists from other cities. The Rio Blanco mine lies close to the environmentally vulnerable Cajas National Park and important water sources for Cuenca and other nearby cities. Environmental groups have always objected to the mine’s plans to use almost 1,000 litres of water per hour.

The conflict came to a head in May 2018. Protestors invaded the mine, damaging roads and burning camps. The government dispatched hundreds of police and soldiers in response. Meanwhile, Yaku Sacha lodged a case in the provincial court bought by the villagers of Rio Blanco and other nearby villages against the mining and environmental authorities. On June 5, judge Paul Serrano found that there had been no prior consultation with locals, as required under the constitution and the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, and ordered a temporary halt on all mine activity. On August 3, the court rejected a company appeal attempting to restart operations.

This was the first time a court in Ecuador had found in favour of indigenous communities because of foreign mining firms failing to carry out prior consultation, and the precedent encouraged others. A similar lawsuit against the Chinese-funded Mirador copper mine is underway, with the plaintiffs referring to the Rio Blanco decision in their case.

An unlikely candidate

Yaku Sacha used to be known as Carlos Ranulfo. He changed his name in 2017. His new moniker is Kichwa for “the water which flows from the mountain”.

In March 2019 posters and stickers of him appeared all over Cuenca. Elizabeth Durazno had one on the window of her car, and there was one by the roadblock in San Pedro de Yumate. Local elections were to be held on March 24 and as candidate for the local indigenous party, Pachakutik, he sought to become governor of Azuay, the province in which Cuenca is situated, under the title “The protector of water.”

It is rare for indigenous people to stand for election in Ecuador, and even rarer for them to win. When we met Yaku Sacha there were still two weeks to the elections. He had tied his long hair back and was wearing a traditional Kichwa necklace, standing by a busy road handing out flyers to passing drivers. Many recognised him and were happy to take a flyer, while others waved him off.

At dusk he headed back to his campaign headquarters – his law office. He showed no signs of fatigue when we asked about the Rio Blanco case. “Legal action, social action and political action are complementary,” he said.

Having just turned 50, Yaku Sacha sees his role as “opposing capitalists and politicians”. Rio Blanco is just one of the lawsuits in which he has represented indigenous communities.

He is sure Junefield and the other companies carried out no prior consultation: “It’s their normal way of operating. They confuse prior consultation with normal social interaction.”

“Ideally, those companies would hold talks with nearby communities before development starts, whether those communities are indigenous or not,” he says. “But because there’s an international treaty specifically for indigenous people in place, those lawsuits are more effective.” He and the villagers also add environmental concerns to their opposition, describing themselves as protecting water resources, rather than opposing the mine.

As far as the government is concerned, they’re all just troublemakers.

In September 2018, Fernando Benalcazar became vice-minister for mining at the Ministry of Energy and Non-renewable Resources. He was blunt in his dismissal of the villagers’ “opposition”, calling them “a small group with ulterior motives stirring up the situation.”

“Ten or so people want to decide for everyone in Ecuador, it makes no sense.” Benalcazar has been a senior mining official for decades and is clearly unhappy with the government’s defeat in court.

He thinks community leaders in Rio Blanco are backed by illegal miners, or their own political ambitions. He thinks the rights of indigenous people are being misused by opportunists who want to bring lawsuits and says “the leaders aren’t the indigenous people … the site belongs to the nation. There’s simply no need for prior consultation.”

He also told us that the checkpoint which Elizabeth Durazno was angry about had been permitted by the national police.

The other checkpoint, built by the villagers of San Pedro de Yumate, has also been a flashpoint. The villagers have used it stop both Junefield vehicles and people from Cochapamba – most of whom support the mine.

Manuel Mueveclea is from Cochapamba, and described the methods of San Pedro de Yumate villagers as “violent and extreme, infringing on our basic rights.” He says people passing the checkpoint are asked if they oppose the mine. If they answer no, they are told not to use that road. He complains his mother was once held there from 6pm until 2am.

Villagers of Rio Blanco and San Pedro de Yumate react fiercely when you mention Cochapamba. Yaku Sacha has received numerous death threats, and he and three others have been kidnapped and beaten near the mine. He recalls being told during the eight hours he was held to “return our job opportunities, return our company money.” And while there’s no proof, locals are sure mine-supporting villagers from Cochapamba are responsible.

Families torn apart

It has now been over a year since the historic court victory. In the opinion of Andres Durazno, the Rio Blanco fish farmer: “We still don’t know what the decision really means.” Winning in court hasn’t solved the daily problems of the villagers and the community is continuing to fragment. When we visited the village we spoke to about 20 villagers, the majority of whom opposed the mine. Yet many of their relations may support it. Families have been torn apart by arguments over the mine.

Elizabeth Durazno enjoys her new indigenous identity and often asks Yaku Sacha to teach her a few lines of Kichwa. She liked sitting down in court as equals with the mining company even more, and laughs as she remembers the scene: “The company thought they’d get rid of us easily.” The victory has turned Rio Blanco into a model for other communities, with visitors often coming to ask for advice, or villagers travelling to “tell our story.”

The villagers’ case focused on water resources, turning the essential liquid into the most important topic in local politics.

Yaku Sacha was victorious in the March local elections and was elected as provincial governor. As Azuay is a major mining province, the arrival of a governor elected on his support for indigenous rights and the environment is bound to mean tensions continue.

Junefield's office in Cuenca declined our requests for an interview.

This article follows on from another also written by Ning Hui, an Initium Media journalist, and Andrés Bermúdez Liévano of Diálogo Chino.

The original Chinese version is available here.

- View this story on The Initium