“Offering”

Smoke billows from a carved out conch shell filled with charcoal and shards of copal (tree resin). This is an offering to the ancestors at Tibes Indigenous Ceremonial Park, the oldest known Indigenous ceremonial site in the Caribbean. It is also considered the largest Indigenous cemetery, as 186 human skeletons have been uncovered there during excavations.

“Ritmo (Rhythm)”

Taíno educator, artisan, and traditional medicine practitioner Po Araní often visits Tibes to connect with his ancestors through song. He plays a steady beat on the mayohuacan with a maraca in hand and an ocarina around his neck—all his own handcrafted Taíno instruments.

All across Puerto Rico, the story of the Indigenous people of the island formerly known as Boriken is marketed to tourists as a centerpiece of its past. For Po Araní, Tibes and other Indigneous sites like it are a deeply spiritual space for gratitude, solace, and reflection in the present.

“Galería de Los Cemis (Gallery of the Cemis)”

Central to this spirituality are the cemis, or deities. North of Tibes lies Caguana Indigenous Ceremonial Park, in the mountainous region of Utuado. Portraits of the cemis on thick stone slabs frame the ancient ceremonial ball game fields, or bateyes.

“Caguana”

This well-preserved piece of Puerto Rico’s pre-Colombian cultural heritage has been the site of important archaeological findings. The Taínos constructed and used the park’s 10 stone-lined plazas for hundreds of years before the Spanish arrived on the island the natives called Boriken in the early 15th century.

“El Agua (Water)”

This petroglyph of a spiral, symbolizing water, stands in front of a Ceiba tree in Caguana Indigenous Ceremonial Park. The Ceiba tree is considered a portal—a connector between the earthly and the spiritual. The Taínos used its thick extensive trunk and roots to construct canoas (canoes): a Taíno word among others like huracán, barbacoa, and tabaco that persist in the modern Spanish lexicon.

In the absence of tribal recognition from the Puerto Rican government, its Institute of Culture charges $3 admission to enter Caguana, where the Taínos and their culture seem a relic of the distant past.

In April 2022, a resolution was proposed in the Puerto Rican Senate in favor of the privatization of the sacred place—seeking to transfer ownership of the lands from the Institute of Culture to the municipality of Utuado. The resolution would have allowed the locality to take necessary action for the site to “reach its maximum potential use to benefit the economic development of the region.” (RCS45)

Indigenous activists and supporters rose in strong opposition to the resolution before it was withdrawn without receiving a vote.

“Direct connection”

Similar ancient petroglyph markings can be found carved in stone all over the island, standing the test of time much like the cultural heritage of their artists. Petroglyphs are not only artifacts but serve as a channel of communication with Taíno deities, as noted in this sign outside La Piedra Escrita, a popular attraction east of Caguana.

“La Piedra Escrita”

The rocks, rivers, and trees are monuments; sanctuaries, temples. From the shoreline to the mountaintops, Boriken is sacred to its people, and they feel a responsibility to protect and preserve it.

But as climate change threatens the islands’ longevity, drastic changes to the environment and its patterns are more alarming than ever. Rising sea levels, strong tropical storms and hurricanes, and high-magnitude earthquakes serve as warnings to Taíno elders who tap into traditional knowledge to interpret nature’s messages.

“Thinking about the way the ancestors would look at things…that often comes to my mind,” said Taíno elder and Indigenous human rights activist Roberto Múkaro Borrero. “What would they think? Just looking around and seeing this place, seeing what it's become?”

“Touring Tibes”

A group of local high-school students funnel into Tibes Indigenous Ceremonial Park, touring the ancient ball fields. Across the grass, Po Araní plays the music of their shared Taíno roots. The Smithsonian cited “island-wide” mitochondrial DNA research revealing that 61 percent of Puerto Ricans carry traceable Taíno ancestry. Po Araní and others in the modern-day Taíno Indigenous community challenge the long held myth that the Taíno Peoples went extinct after the Spanish colonized their homeland in the 1400s.

“If they can make you think that the people who were here originally are no longer here, they could just do whatever they want. And they have been,” said Roberto Múkaro Borrero. “It's in the best interest of the colonial machine that seeks to really remove us from our connection with the Earth.

The colonization of Puerto Rico all those hundreds of years ago upset the gentle balance the Taínos held with nature—one that Borrero and other elders feel hasn’t been restored since.

“Todo Que Necesitamos (Everything We Need)”

Po Araní examines a native tree, wielding an encyclopedic knowledge of the traditional plants at Tibes Indigenous Ceremonial Park. He owns and operates Tintura Madre, an online storefront that sells tincture blends that harness the medicinal properties of the flora and the fauna of his homeland.

“Indigenous peoples are great observers of the world around them,” said Borrero. “It's been getting hotter and science affirms this or confirms this. Although we don't need modern science to do that, we can see the changes.”

“Third Time’s the Charm”

Daniel Silva, a Taíno resident of Vieques, lives between two national reserves and just a stone’s throw from the small island’s coastline. When Hurricane Maria destroyed his home in 2017, he laid down cement.

“Originally I built wood, because I don’t like cement houses. But Hurricane Maria made me understand I needed a cement house.”

An earthquake later shattered that foundation, too, forcing him to reconstruct his home again.

“The earth is shaking as it has never shaken before. I think this is something irreversible.”

“El Punto de Vista Ancestral (Ancestral Perspective)”

Silva is a traditional Taíno artisan and archeologist. He grows native fruits, vegetables, and other plants on his plot and sells his handmade Taíno art.

“Raíces (Roots)”

Living off the land, Silva says, helps him connect to his cultural heritage and colors his views on the changes happening on the island, especially the rapid rate of deforestation and industrialization.

“[The ancestors] made their homes of wood and straw, but there were forests, real forests, where the trees were thousands of years old. Wherein everyone worked together to make their bohio (huts) strong, and if a storm took it down, they had the forest. But what’s left today?”

“Daka Taíno (I Am Taíno)”

In an original song based on what his ancestors might have sung when they saw the Spanish approaching the coastline of Boriken, Daniel Silva conveys his pride for his Taíno roots through a grim warning:

Mayani Macana! Guayba! Anli Arihuna! Daka Taíno, Daka Taíno, Jajom.

(No me mates, vete! Enemigo Extranjero! Yo soy bueno, yo soy noble. Gracias.)

(Don’t kill me, go away! Foreign enemy! I am good, I am noble. Thank you.)

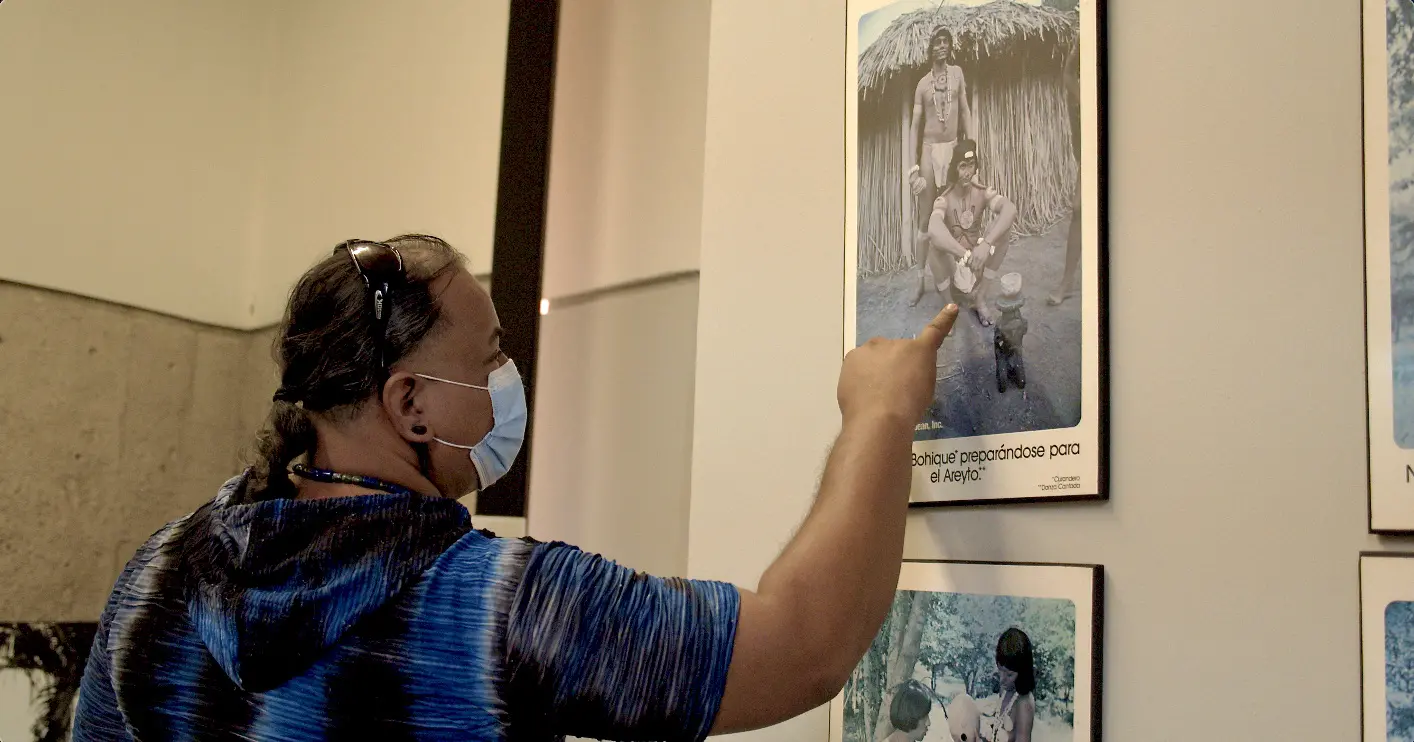

“Living History”

At the entrance to Tibes is a history museum home to a collection of historical artifacts and reenactments of Taíno life in pictures. In the photo, the casique (chief) and bohique (shaman) prepare to lead a Taíno ceremony, or areyto. Not pictured, behind Po Araní, is a skeleton in the fetal position that was uncovered at Tibes, under fluorescent light in a glass enclosure with a sign marked “Human Remains”. Po Araní said he considers this display disrespectful and would prefer his ancestors rest on the grounds of the park where they were initially buried.

Especially in the context of the myth that the Taíno Peoples went extinct, this grotesque display pokes at the wounds left by hundreds of years of colonial intent to undermine and erase Indigenous perspectives.

Herein lies another crucial conflict between Indigenous practices and the advancement of modern science and archeology. The two worldviews may seem entirely oppositional given the island’s history and present reality.

“New Horizons”

Isabel Rivera-Collazo, a Puerto Rican native and professor of biological, ecological, and human adaptation to climate change, challenges the idea that science and Indigenous spirituality must be squarely at odds. She works with Taíno elders on the island to incorporate traditional ancestral knowledge into her climate and anthropology research, including her own heritage and personal connection to la patria (the homeland).

Though she works diligently to address her community’s needs and questions and contributes to the National Climate Assessment, she emphasizes that the preservation of the Taíno culture is essential to the island’s longevity.

“The holders of the traditional knowledge are the ones that are carrying the burden of climate impacts, said Rivera-Collazo. “We are losing this richness and this depth of knowledge with elders dying or people migrating.”