For three months, Chicago flooded more than a dozen neighborhoods hit hardest by COVID-19 with vaccines, a key program called Protect Chicago Plus that was intended to immunize those vulnerable communities as quickly as possible.

A WBEZ analysis of public vaccination data and additional data obtained through the Freedom of Information Act shows Protect Chicago Plus succeeded in boosting vaccination rates in some of these areas ravaged by the pandemic. But the impact was uneven and hasn’t lasted. Across Chicago, vaccination rates still are not equitable across racial groups.

As the initiative winds down by the end of May, many health providers and community organizations that were involved are wondering, what’s next to keep this momentum going?

“The system inherently reaggravates the historic problems we’ve always had and creates unequal distributions,” said Dr. Ali Khan, executive medical director at Oak Street Health, a large group of clinics. “For a city like ours, Protect Chicago Plus was so bold because we were acknowledging the normal patterns, the normal channels, don’t work.

“Now, how do we apply that same logic for, not a sprint, but a marathon?” Khan asked.

“They were going as fast as they could”

Less than a month into the pandemic in Chicago last year, the city’s long-standing health inequities became shockingly clear. About 70% of the people who were known to have died of COVID-19 in Chicago were Black. Lives lost and cases of the deadly virus in certain city ZIP codes skyrocketed, disproportionately higher than elsewhere in Chicago.

When two vaccines were finally authorized before Christmas, Chicago leaders talked about getting shots to the communities hit hardest by COVID-19. But a WBEZ analysis of vaccine distribution data found most doses were sent to large hospitals, and the potentially life-saving injections were going into white arms at a disproportionate rate.

It wasn’t until February that the city started shipping doses to a wide array of providers.

“We did lots of shouting in the first month,” said Amy Valukas, chief operating officer at Erie Family Health Centers. The organization got 400 doses in the first two weeks of vaccine shipments, followed by 600 in mid-January. Their largest shipment of 1,800 vaccines came in mid-February.

By comparison, large hospitals and health systems including Rush University Medical Center, Northwestern Memorial Hospital, UI Health and University of Chicago Medical Center each received nearly 2,000 doses each week the first two weeks. By January, their weekly allocations nearly tripled.

This was by design, said Dr. Allison Arwady, commissioner of the Chicago Department of Public Health. Chicago, and the rest of the country, vaccinated health care workers and nursing home residents and staff first.

“In hindsight, they were going as fast as they could,” Valukas said.

In some cases, small clinics that are traditionally the lifeline for the most vulnerable people didn’t have the money, staffing or capacity to ramp up vaccinations quickly, like big hospitals did. Consider the ultra cold freezers required to store the Pfizer vaccine and the space needed for people to wait six feet apart for 15 to 30 minutes after getting a shot. There are also health care deserts on the South Side, meaning fewer providers to ship vaccines to.

In February, the vaccines were no longer restricted to only health care workers and nursing homes. Chicago began blitzing 15 communities prioritized in Protect Chicago Plus with extra doses and special pop-up vaccination events. Unlike vaccination sites in the rest of the city, which restricted who could get vaccinated, anyone 18 and older in these neighborhoods could get shots.

Public health officials say that was crucial to curbing the virus as it spread through homes with generations of families living under the same roof and working jobs that put them at risk, like driving a bus or putting goods together at manufacturing facilities.

“I’m going to be honest. People around the country thought we were nuts, that this would not be something feasible,” Arwady told WBEZ in late March. “We know that those have been the communities that have been hit the hardest, and I really see it in a lot of ways as a test of ‘put your money where your mouth is’ and ‘let’s see if we can do this.’ ”

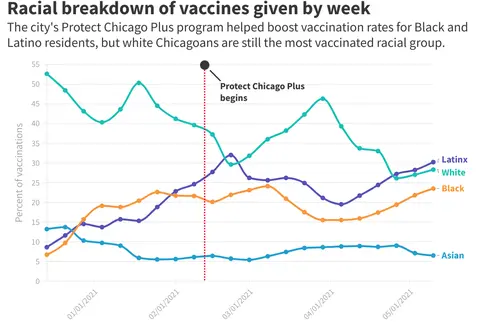

Once those sites opened, the racial breakdown of who was being inoculated almost immediately started to shift.

Over Valentine’s Day weekend, Oak Street Health and the Northwest Side Housing Center launched the first Protect Chicago Plus vaccination site at Steinmetz High School in Belmont Cragin. More than 800 residents of Belmont Cragin got first doses the Saturday the temporary clinic opened. Previous single-day records for vaccine administration at the time hovered around 500.

The following week, vaccination data shows Latinos surpassed whites as the group getting the most first-dose shots of a COVID-19 vaccine, according to a WBEZ analysis of weekly vaccination data. The analysis also showed the proportion of first doses going to Black and Latino residents narrowed significantly throughout the month of February, with each racial group making up at least 20% of all first doses.

WBEZ obtained additional data through FOIA to determine if residents of Protect Chicago Plus ZIP codes were the ones being vaccinated at the pop-up vaccination events. Data showed just 2% of people vaccinated at these events through March 8 came from outside the communities they were meant to serve.

In other words, the program was working as intended.

“I remember one guy, specifically saying, ‘Wow, we’re being put first this time?’ ” said Pastor James Brooks of Lawndale Christian Health Center. “That meant a lot. It meant that areas such as North Lawndale that suffer with high health disparities … the city was looking out for their best interest and wanting to make sure that they were cared for first.”

In an interview with WBEZ in late March, Tamara Mahal, who is an integral part of the city’s vaccination effort, said Protect Chicago Plus was on time.

“Although from the sidelines, it might appear like it was us being a little bit late to the game, I actually think there was a lot of intention,” Mahal said.

It takes time to build trust, she added.

“Even if we had wanted to just land and go and give out all this vaccine on the same day, we had to build the trust, we had to get the testimonials,” Mahal said. “We had to lay the foundation and the groundwork to ensure things like Protect Chicago Plus were successful.”

White Chicagoans are still the most vaccinated in the city

Though improvements to vaccine distribution narrowed racial inequity, it didn’t fully close the gaps.

Despite the rapid increase in vaccination rates among Latino and Black Chicagoans during the months of February and March when Protect Chicago Plus was in full swing, by April, the percentage of first doses administered to Latino and Black residents started to slip again. White Chicagoans continue to be the most vaccinated racial group in the city.

As of May 12, of Chicagoans who have gotten at least a first dose, 19% are Black, 23% are Latino, 38% are white, and nearly 8% are Asian. The race of another 8% is unknown. The city’s population is about one-third Black, one-third Latino, one-third white.

This has many health providers and community organizations concerned that the gains in equity brought on by Protect Chicago Plus could fade.

“It is hard to communicate to folks and communicate consistently and build awareness when you are only somewhere in a short amount of time,” Valukas said.

Erie has deconstructed its temporary vaccination site in West Humboldt Park and shifted to offering walk-ins at permanent clinic locations in East Humboldt Park.

James Rudyk Jr., executive director of the Northwest Side Housing Center, wrestles with the official end of Protect Chicago Plus.

“It feels like the one time where we actually got it right,” Rudyk said. “There’s so much going on around us. I think about the violence and the police shootings. … But then I look at what happened at our vaccination clinic, and it makes me hopeful.”

The temporary clinic at Steinmetz vaccinated more than 9,500 people in the heavily Latino neighborhood during the eight weeks it was open, according to Oak Street Health, which ran the operation. When it closed, there were some 3,000 people on a waitlist for a shot, Rudyk said. That waitlist has since cleared by sending people to get shots elsewhere.

To keep the momentum going, Rudyk said the housing center is partnering with Lurie Children’s Hospital to open a vaccination clinic inside Iglesia Evangelica Emanuel Church in the area. The idea is to vaccinate families now that anyone 12 and older can get a Pfizer vaccine.

“In these Protect Chicago Plus communities, there’s still room for people who are excited about getting their first shot, or are finally ready to commit to getting their first shot, but haven’t been able to commit because of timing or access,” said Khan, of Oak Street Health.

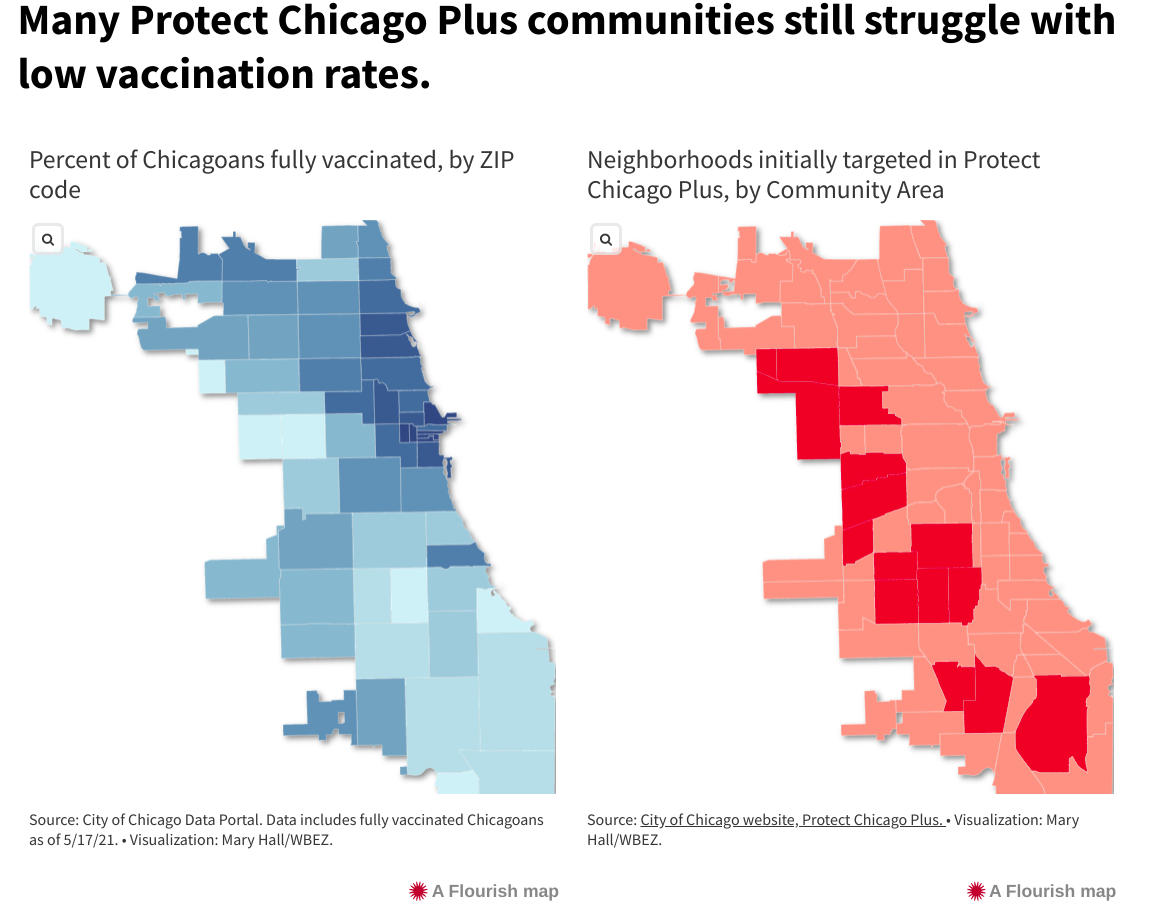

There are still many communities in Chicago with low vaccine uptake. Of the 10 ZIP codes with the lowest vaccination rates in the city, six were part of Protect Chicago Plus. In Englewood and West Englewood, which are majority-Black neighborhoods, 18% and 22% of residents are fully vaccinated, whereas, citywide, more than 35% of residents are fully vaccinated.

By contrast, 50% or more of the residents in the top 10 ZIP codes are fully vaccinated. None were part of Protect Chicago Plus.

What Chicago’s planning next

In a recent interview with WBEZ, Arwady said her department is now shifting its focus to the 13 ZIP codes with the lowest vaccination rates. In recent weeks, as the pop-up clinics have come to an end, the Department of Public Health is driving a vaccination bus around town, stopping at schools and parks in these neighborhoods on the weekends when it’s easy to get people to come out.

The vaccination bus schedule posted online will target four majority Black neighborhoods — South Shore, Englewood, Roseland and Austin — through May. These neighborhoods have some of the city’s lowest vaccination rates. Anyone 12 and older is eligible, and appointments are not required.

The health department has also issued two $10 million requests for proposals to continue some of the work Protect Chicago Plus started. The first, released in March, was seeking “Regional Vaccinators” for five equity zones on the South and West Sides to operate mobile vaccination sites and administer shots in specific settings, like factories.

“We’re not thinking in terms of if a site can [vaccinate] thousands a day. We’re like, ‘Can a site do hundreds a day? And where can we put additional sites?’ ” Arwady said.

The second request for proposals, released in early May, is for organizations interested in partnering with the city to tackle health and racial inequities across Chicago. Dubbed the “Health Chicago Equity Zone” program, the effort would last for the next four and half years and would aim to tackle many of the goals outlined in the city’s Healthy Chicago 2025 plan, which was in development before the pandemic hit.

Rodney Johnson of One Health Englewood, a community organization focused on improving health outcomes, said a lot of people are not necessarily against getting vaccinated, but want to see others go first and make sure there aren’t major negative side effects.

Now, he and many other community organizations say the big lift will be providing people with information, an easy way to get vaccinated and helping them overcome any concerns.

Dan Fulwiler illustrates the hard work ahead. He runs Esperanza Health Centers on the Southwest Side, a group of community clinics that mainly serves low-income people of color where COVID-19 has seethed. Esperanza has administered just over 81,000 total doses and was part of Protect Chicago Plus.

Inside a cavernous former fitness center in West Englewood, Esperanza set up a vaccination clinic where these days up to 150 people a day trickle in for a shot. It used to be 500 a day.

“I’ve said in the past that I wasn’t worried about vaccine hesitancy,” Fulwiler said recently amid a massive room of mostly empty chairs set up for the vaccination process. “That was about three, two months ago, when we still had plenty of people of color from these neighborhoods really banging down the door to get the vaccine. But that’s stopped. And you know, it’s across all demographic groups. … Now I think that our job really is to figure out, why are they hesitant? And how many of them can be convinced?”