Determined to get noncustodial fathers to do more to support their children, Colorado took a bold step: It stopped making these parents repay the government for welfare payments their families received.

And nearly three years into the social experiment, the state’s poorest families have seen a cascade of benefits, Colorado officials say. Child support payments paid by low-income fathers increased considerably — with all of the money going to the children, not a state agency. Relationships between co-parenting exes got better. And kids were given the advantage of more financial and emotional support from both their moms and dads.

“This is about getting money to families and not letting the government keep it," former Colorado state Sen. John Kefalas said. “Over the years, it has exceeded expectations.”

Maryland could take this step and a handful of others to immediately transform its rigid and punitive child support system. In doing so, the state would join efforts across the country to address counterproductive policies and practices.

An investigation by The Baltimore Sun found that Maryland’s child support system is actually hurting some of the state’s neediest families and their communities, especially struggling Baltimore neighborhoods where millions of dollars of child support debt is concentrated. The Sun’s analysis found that parents owe a collective $233 million in 10 city ZIP codes, money that is largely considered uncollectable.

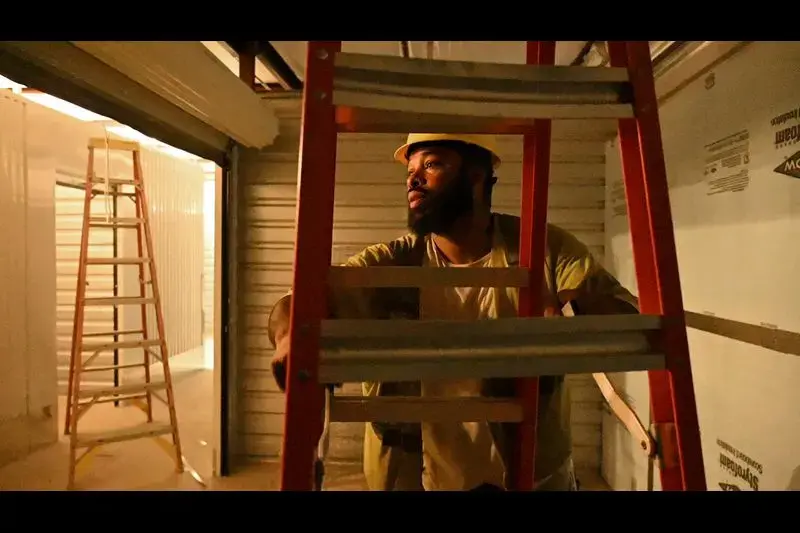

The debt tears families apart and can drive men into the underground — and sometimes illicit — economy. Often, it can be traced to unrealistic orders that are based on “imputed” income: what a parent who is unemployed could earn if he had full-time job. The arrears trigger enforcement actions that can make it harder for a parent to get and keep a job, such as suspending his driver’s license or the professional license required for nursing assistants, barbers, plumbers and other occupations. The problem gets worse if a parent is incarcerated and child support bills continue to run up while he is behind bars.

The government collects child support from noncustodial mothers, too, but most cases involve fathers. In Baltimore, nearly all of them are African American, and many are poor. The burden of their debt is seen as a significant problem afflicting poor Baltimore neighborhoods.

To get better outcomes, advocates say, lawmakers could stop routinely basing child support orders on fictitious imputed income. Maryland could look to other states to do a better job making sure parents who need their driver’s licenses for work don’t lose them over unpaid child support.

And the state could decide to stop sending child support bills to men in prison. Continuing to bill incarcerated parents creates debt that mounts when they are behind bars and have virtually no ability to make payments. The debt that accumulates often does not result in money for kids, but does act as a deterrent for ex-offenders seeking legitimate employment, experts say.

Kathryn Edin, a nationally recognized poverty researcher at Princeton University, said the system is exacting “an incredible cost."

Edin says Maryland has the chance to “do something profound” to address problems in the child support system that have festered largely because the men involved have made mistakes.

“Many of us want to look at an out-group in society," Edin said, "and wag our finger rather than sit up and solve the problem. But these are our kids; they’re worth too much for that.”

Some Maryland lawmakers have pushed for changes with little success. More bills are before the General Assembly again this year, including one that would update the state’s decade-old guidelines for setting orders. That bill, which passed the House, would also encourage judges to base orders on a parent’s actual circumstances, rather than routinely assigning imputed income. Additionally, orders would factor in more money for a poor parent to live on.

Other bills, introduced in both the House and the Senate, would allow more inmates to have their child support orders frozen while they are behind bars. The proposals would allow child support officials to suspend orders after someone is incarcerated for six months, down from Maryland’s current 18-month standard.

The issue has also gotten the attention of Baltimore candidates, including those running for mayor and City Council president. Some see addressing unrealistic orders and the accumulation of child support debt as contributing to the city’s crime — and consequently, in desperate need of attention.

For solutions, Maryland could look to successes in other states.

Colorado no longer treats welfare like a loan to fathers. Unlike most states, the entirety of the child support order now goes to the family even when the mother and children are on welfare.

Using child support to repay welfare has been at the heart of the child support system since its creation 45 years ago. It is based on the idea that if fathers were held responsible for providing financially, their children would be less likely to need public assistance. The practice has meant that mothers have had to sign away their rights to child support in exchange for getting cash assistance from the government.

Colorado began to investigate the change as officials were seeking to collect payments more consistently from low-income noncustodial parents, said Larry Desbien, a state child support administrator. Research suggested that if fathers knew their child support payment was going to their kids, the dads would pay more. And the mothers and children, in turn, would be better off and over time less likely to need public benefits.

Since Colorado stopped taking the money for welfare repayment, fathers on average are paying more, Desbien said.

Kefalas, the former Colorado lawmaker, was the lead sponsor on the bill to make the change. Key to its passage, he said, was educating people about the issue in an effort to get broad support for the proposal. The change took effect in April 2017.

Kefalas said persuading lawmakers to make the switch was “challenging at first" because of budget issues. In the end, he said, it was a bipartisan bill that won the support of some of the legislature’s most conservative members.

“We said, ‘Look, wouldn’t you rather children and families have this for their needs and economic security?’ ” he said.

Besides the increase in payments, Desbien said, surveys show four out of 10 mothers report improved relationships between their children and the children’s fathers after the change. They also felt more encouraged to communicate with the fathers.

Colorado is taking other steps, too. Desbien said that when a parent comes into their office to open up a child support case, workers also look for other resources to benefit both moms and dads. That became easier after the state legislature agreed to set aside money to boost employment services for parents who owe child support.

“I want our program to be one that parents don’t run away from but come to for support,” Desbien said. “For so many years it was hammer, hammer, hammer with enforcement. It drove many parents underground.

“When parents are willing [to pay] but unable, all the enforcement tools in the world are not going to make a difference.”

It became easier for states to allow a parent’s child support to go to his family, not the government to repay welfare, in 2008. The federal law was changed to allow states to send the family up to $100 a month for one child and $200 for two or more children without having to repay Washington for that portion of a family’s welfare benefits. Before that, all of the money the states collected from the noncustodial parents needed to be divided between the federal and state governments to offset their cost in jointly providing welfare.

Maryland finally took advantage of the 2008 law more than a decade later, last July. So families are now getting the first $100 or $200 of a monthly child support payment. The state still holds back for welfare cost recovery the remaining amount of a child support order, money that collectively comes to an estimated $1 million a year, according to Vicki Turetsky, a former federal child support czar who has studied Maryland’s system.

At least 20 states, including Maryland, have some type of policy to address arrears that accumulate during prison sentences, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. Federal rules give states the authority to automatically suspend child support orders when parents are incarcerated for six months or longer. And as of 2016, the federal government requires states to notify parents in prison that they have a right to ask for their payments to be suspended.

Nationally, a quarter of inmates are estimated to have child support orders. In Maryland, a 2005 University of Maryland School of Social Work study found these inmates often leave prison with debt, routinely as much as $20,000. Advocates want Maryland to freeze orders after a parent has spent six months in prison, not after the current 18 months.

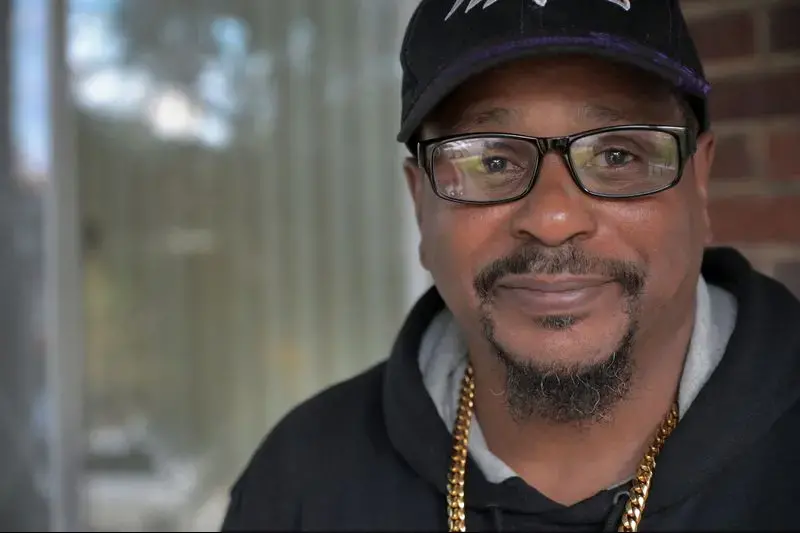

In California, Assemblymember Reginald Byron Jones-Sawyer Sr. is pushing for that state to resume automatically suspending orders when parents are incarcerated for at least 90 days. He said the idea is not to give fathers a pass on taking care of their children, but to ensure that they don’t return to society facing a mountain of new debt.

Supporters believe the change encouraged former prisoners to obtain employment and pay their child support. Although he does not have data on the law’s effectiveness, Jones-Sawyer said he has talked to families who say they’re better off because of it.

“I believe we have reunited a lot of families because the wall of debt is not there,” he said. “When you get out and have $20,000, $30,000, $40,000, $50,000, $60,000 in debt and you can barely get a minimum wage job, that gets very difficult.”

People who study the child support system say another area that needs improvement in Maryland is the practice of suspending driver’s licenses. Because of federal requirements, every state has policies that deal with revoking driving privileges for unpaid child support. But more than a dozen have taken various steps to make it easier for these parents to continue to work and pay their orders, the National Conference of State Legislatures reports.

While Maryland has exemptions on the books for people who need their license to work, advocates say the bureaucracy frequently does not administer the policy well. For instance, men who have been told their license was being reinstated have discovered months later that it never happened. Many advocates also say that withholding licenses from low-income fathers almost always is counterproductive and merely makes it hard to get and keep work.

Maryland leaders could look, as well, to various programs across the country that get better results for families.

One Minnesota county operated an alternative court that helped unmarried parents with child support orders manage their situations.

The ex-couples attended workshops, were referred to social services for various needs and developed co-parenting plans with the help of mediators. The agreements provided custody and visitation for the fathers — something child support orders do not typically do in Maryland. The agreements also captured the support, outside of money, each parent could provide, such as helping their kids with homework.

The court found fathers who participated paid their orders at a much higher percentage and mothers said their ability to co-parent with the men got a lot better. Ultimately, children began spending more time with their dads. Despite its success as a demonstration project, the Minnesota court stopped its program when the grant money ran out.

Bruce Peterson, a retired Minnesota judge, helped create the alternative court. “Don’t make this about child support,” he said. “Make this about successful unmarried parenting.”

Although launching an alternative court with extensive wrap-around services is expensive, Peterson said, the work could be accomplished by coordinating various services already available in a community, including mediation, community college and robust nonprofits that serve poor families.

A similar effort is underway in Baltimore County.

Retired Baltimore County Circuit Court Judge John O. Hennegan leads a nearly 20-year-old program for noncustodial parents who are behind on their child support orders. The program works to get them into good-paying jobs and finds help for any substance abuse problems. Hennegan said the program assists parents in getting their driving privileges restored and suspensions to their professional licenses lifted.

For those with debt that accumulated while they were in prison, he said, the program helps them figure out if any portion can be waived. The program also connects its participants to mediation services.

“If a person has a job — and it is [a] decent-paying job that gives them self-esteem and they have money in their pocket — as a result, they are more involved with their family,” Hennegan said.

Turetsky says taking a serious look at what changes could be made in Baltimore, and across Maryland, would be worthwhile for not only families, but their communities as well.

“There is such capacity for good and harm in the child support system,” Turetsky said. “Nobody is saying that parents shouldn’t support their children. But how do you get there? There are proven ways to get there.”