In one of the most corrosive presidential campaigns in recent American history, Utah’s top candidates for governor made a television commercial together.

It wasn’t your typical political ad.

On one side of the screen was Chris Peterson, the Democratic candidate, an affable man looking earnestly into the camera. On the other was Spencer Cox, his Republican opponent, with a similar expression.

They cheerfully acknowledged that they disagree on many things, but then added something unusual for America in 2020.

“Win or lose, in Utah we work together,” said Peterson, who would be crushed in the November elections.

“Let’s show the country there’s a better way,” said Cox, who, soon after his victory, criticized Republicans for attacks on the elections’ legitimacy.

When it comes to politics, Utah has long claimed things are different here.

Political viciousness is for other places, politicians will tell you. Legislators are more polite, more willing to compromise.

It might make you wonder: With U.S. politics so divided, could this idiosyncratic state in the heart of the Rockies show America a better way?

Ehhhhhhh. Sort of.

***

Salt Lake City turned out to be the end of the AP’s road trip. Three of us have been trying to make sense of a year wracked by coronavirus, economic devastation, sometimes-violent protests and an election campaign that ended with President Donald Trump, the clear loser, insisting he had won.

The year had offered so little good news.

So we came to Utah, hoping.

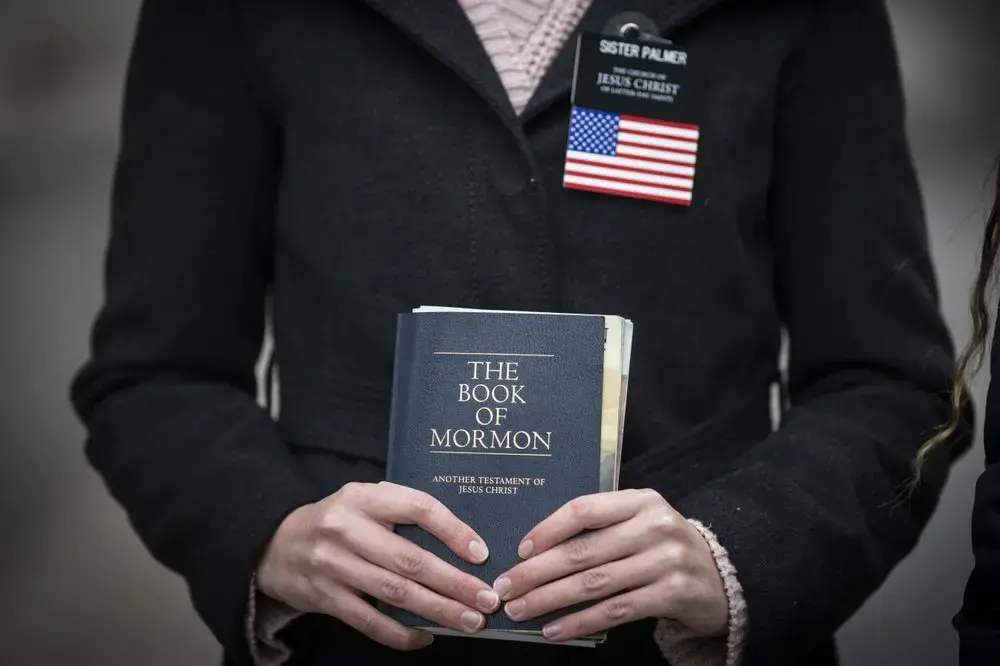

It didn’t take much poking around to realize that the state’s reputation — overwhelmingly white, overwhelmingly Republican, dominated by a cultural conservatism inherited from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints — was only part of the story.

The other part is a surprising political complexity and slowly changing demographics. Utah, it turns out, is a place where right-wing Republicans have fought for undocumented immigrants and deeply religious legislators have enacted strong protections for gays and lesbians.

It is one of America’s most conservative states, but has one of its most liberal cities: Salt Lake City, with its throngs of Democrats and array of hipsters.

What is going on?

“I really do think it’s different in Utah,” said state Rep. Robert Spendlove, a Republican economist. “In Utah we really do have a sense of wanting to work together.”

“There are levels of civility, of decorum, that are unique to the culture of the state,” said state Sen. Luz Escamilla, a Democrat.

But Utah culture also includes a powerful streak of conformist perfectionism, and generations here have faced the pressure of living up to a mythological ideal: the happy family with a string of polite, hard-working children.

So some of that outward political civility is what people around here call Utah Nice, where viciousness can be hidden behind a fake smile and a batch of fresh-baked chocolate chip cookies.

Jim Dabakis, a former Democratic state senator, said he never faced a harsh word from a Republican during his years in office — but he said they still worked to quash pretty much every progressive bill he backed.

“This is a society of very passively aggressive people,” he said.

He argues that Republicans’ crushing majorities in the state House and Senate and longtime control of the governor’s office have warped Utah’s politics.

“It is simply one party that is in total, complete, absolute control and then saying, ‘We all get along so well,’” Dabakis said.

But it’s also complicated.

“The Utah Nice thing, it can be superficial, but there can also be substance to it: It’s a method of getting from A to Z,” said Brian King, the Democratic House minority leader.

In many ways, the overwhelmingly white, male and Mormon legislature doesn’t reflect the changing state. Utah is no longer a cliché of homogeneity. It has an increasingly large Latino population and growing numbers of other racial minorities, as well as ever more non-church members.

It’s no melting pot — the state is still roughly 81% white and 62% Mormon — but that’s down considerably from a couple decades ago.

Utah has become harder to pigeonhole, culturally and politically.

While it’s more conservative than much of the U.S., it has very strong LGBTQ worker and housing protections. Polls show Utah has some of America’s highest public support for LGBTQ-protection laws — including among Mormons.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, which did much to mold the state’s ethos, also has become harder to pigeonhole.

While the church has traditionally been overwhelmingly conservative and Republican, today there are increasing numbers of liberal members. The church has also begun to directly address its history of racism, including a ban on Black priests it lifted decades ago.

The church’s history — believers arrived here in the 1800s fleeing religious persecution — also helps explain why many conservative Utahns are staunch defenders of immigrants and refugee rights.

This year, as the political atmosphere grew ever more virulent, the church urged followers to avoid partisan rancor.

***

Rancor was what we expected to see when we set across America, and there was no lack of it. We found racial tensions in an Illinois “sundown town” where Black people were once welcome only by daylight, and in rural Mississippi, where they still face obstacles to voting; we found distrust and discontent in Appalachian Ohio.

We also found Americans who struggled valiantly — two women building a family amid poverty; a Black man willing his wife from her COVID-induced coma.

In Utah, we found something else: A place that seems to work — but perhaps only because it is Utah.

Founded by believers in what was then a small, fringe religion, Utah was then lost in mountain desolation, and widely viewed with suspicion.

The insularity that resulted has faded, but it’s still a place marked by its own distinctiveness.

Sometimes that means politicians more willing to get along. And sometimes it means the platitudes of Utah Nice.

So King can celebrate legislators finding common ground even as he grumbles about political superficiality.

That’s Utah, he said: “It’s not black and white.”