The soul of America is its promise of ever-expanding freedom, equality, and opportunity. The paradox of America is that over four centuries our Founders and our leaders reneged on this promise by embracing a devil’s bargain with slavery, segregation, racial superiority, and racism.

It’s like opposite sides of the same coin – good and evil, shiny and tarnished. They are opposite ends of the long arc of the moral universe that the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and President Barack Obama said: “bends toward justice.”

Anyone who doubts the centrality of slavery, segregation, and racism to the American story – from 1619 through today and for generations to come – isn’t paying attention.

Four hundred years after Jamestown colonists brought the first enslaved people to America, our original sin and efforts to redress it play out every day in post-Ferguson reforms and sadly in the heavy death toll Covid-19 claims among blacks.

Over the past two centuries, perhaps no other region of the country has been so entwined as St. Louis, Missouri, and Illinois with America’s struggle to extract the poison of 1619 from its soul. Race is at the heart of the biggest stories in St. Louis this century.

Since Ferguson, reform-minded prosecutors won elections in St. Louis, St. Louis County and around the country. Municipal court reform, bail reform, police and prosecutorial misconduct, racist police postings on social media – all dominate the news. St. Louis’s first black prosecutor filed a lawsuit this year under the Ku Klux Klan Act alleging a conspiracy against her by the white police union and legal establishment to block her reforms. Yes, race is central to it all.

Meanwhile, the first 12 people who died of Covid-19 in St. Louis were black. Seventy percent of those who died in Chicago through the second week of April were black. The inequality in life expectancy between rich and poor zip codes, white and black zip codes, never has been so stark.

Nikole Hannah-Jones’ 1619 essay in the New York Times magazine last year on the centrality of race to the American experience is a profound statement of a truth that has long been in plain sight: Slavery, segregation and racism are central to what America means. They are central to the histories of St. Louis, Missouri and Illinois.

It is a continuum running from Jamestown, to the Declaration of Independence, to the Constitution, to the Missouri Compromise, to Dred Scott, to the Lincoln-Douglas debates, to the 1917 East St. Louis race riot, to J. Edgar Hoover’s dirty tricks against Rev. King, to the FBI’s planting of anti-King editorials in the Globe-Democrat, to the COINTELPRO plots against Black Liberators in Cairo, Il., to the Jefferson Bank protests, to the landmark housing discrimination victories won against racial covenants and exclusionary zoning, to the unveiling of the Veiled Prophet, to the nation’s biggest school desegregation program, to the legal fights of two Missouri attorneys general to end desegregation, to the Kirkwood City Hall massacre, to the death of Michael Brown on a Ferguson street.

Many of these episodes represent both the good and bad – the evil of racism and the fights to overcome it. The Declaration declared all men equal, but did it include blacks? The Constitution protected slavery but never mentioned it directly. Sen. Stephen A. Douglas said the Founders wanted slavery “forever;” but Abraham Lincoln called it an evil that had to be expunged because a House Divided could not stand. It didn’t.

The nation’s biggest legal fights against housing discrimination were in St. Louis, and African Americans won them. The nation’s most expensive court-ordered school desegregation program was here, and it eventually attracted the political and public support to raise graduation rates and college-attendance rates for four decades. Michael Brown died near St. Louis, but the criminal justice reforms and rekindled racial enlightenment that followed have been transformational.

Consider the long ago history of race before we were born – the Missouri Compromise, the lynching of Francis McIntosh, the murder of abolitionist newspaper editor Elijah Lovejoy, hundreds of freedom suits like Dred and Harriet Scotts’, Missouri’s ban on teaching black children and refusal to admit free blacks, Illinois’ refusal to recognize blacks as citizens, the 1916 housing segregation law passed in St. Louis, the 1917 East St. Louis race riot where about 100 blacks were murdered, the disappearance of Lloyd Gaines who sought a legal education at Mizzou, the Kraemers’ refusal to sell a house on Labadie to J.D. Shelley because of racially restrictive covenants, the Fairground swimming pool riot.

And consider the racial history we have witnessed in our lifetimes:

- 2018 – Clayton police racially profile a group of black Washington University students walking home from IHOP and falsely accuse them of not having paid their bills.

- 2017 – St. Louis police illegally “kettle” protesters and spray them with chemical agents as they protest the acquittal of an officer who killed a fleeing suspect.

- 2015 – students at the University of Missouri force President Tim Wolfe to resign after he refuses to talk to them during a Homecoming parade protest against Mizzou’s long history of segregation.

- 2014 – Michael Brown is killed by a police officer on a Ferguson street prompting a federal investigation that unearths unconstitutional police tactics, revealing the abuse of municipal courts and opening people’s eyes to the long road ahead to racial understanding.

- 2008 – Charles “Cookie” Thornton, once a symbol of integration in a wealthy, white suburb, murders two police officers and three city officials at the Kirkwood City Hall. The city – black and white – searches for racial understanding and reconciliation.

- 2007 – Mayor Francis Slay forces out the first African American Fire Chief, Sherman George, when George refuses to make promotions based on a test he thinks discriminated against blacks.

- 1999 – Sen. John Ashcroft blocks the appointment of Ronnie White to the federal bench in St. Louis, misrepresenting White’s decisions on capital punishment as soft on crime. He later admits he was wrong and apologizes to White.

- 1980s and 1990s – Two attorneys general – one Republican and one Democrat – try to kill the St. Louis school desegregation program. Each, Ashcroft and Jay Nixon, uses opposition to desegregation to leverage political advantage.

- 1995 – Nixon persuades the U.S. Supreme Court to bring down the curtain on the era of court-ordered school desegregation in Kansas City, Mo. even though segregation remains. The decisive fifth vote comes from Clarence Thomas, the former assistant Missouri attorney general.

- 1981 – Ashcroft visits the Justice Department, persuading the new Reagan appointees to oppose St. Louis’ inter-district desegregation program.

- 1972 – Percy Green, the civil rights activist who climbed the unfinished Arch in the 1960s to dramatize job demands, organizes a protest of the Veiled Prophet ball that unmasks Monsanto VP Tom K. Smith. The local papers keep Smith’s identity secret.

- 1970 – Black Jack incorporates as a town to keep out blacks. A few years earlier Alfred H. Mayer refuses to sell a house in Paddock Hills to bail bondsman Joseph Lee Jones and his white wife. The federal judges in St. Louis – all hostile to civil rights – back Black Jack and Mayer, only to be overruled by appellate courts and eventually the Supreme Court.

- 1963 – William L. Clay Sr., Norman Seay and others in the Congress of Racial Equality are jailed for blocking the entrance to the Jefferson Bank, which refuses to hire black tellers. The newspapers and local ACLU oppose the protest, but it leads to more than a thousand new jobs.

- 1956 – Dr. Howard Phillip Venable, a noted African American eye doctor, is building a home in Creve Coeur when the city denies him a plumbing license. The city decides suddenly that it needs a new park and takes his land. U.S. District Judge Roy Harper, notoriously opposed to civil rights, tosses out Venable’s suit. The park stands where the late doctor was building. At least it was recently renamed Venable park.

This modern history of race is based on first-hand observation as a journalist with a front-row seat on civil rights, here and in Washington D.C.

I saw Ashcroft arrive at the Justice Department building on Pennsylvania Avenue to ask Reagan appointee William Bradford Reynolds to withdraw support for St. Louis school desegregation – which he did. I saw a feeble Thurgood Marshall retire from the Supreme Court as Clarence Thomas waited in the wings. I saw Thomas confirmed and watched him bringing down Justice Marshall’s legacy of school desegregation. I editorialized against Nixon’s attempts to kill the St. Louis school desegregation program.

I saw Kirkwood reel from the City Hall killings where a friend was shot and reported on months of reconciliation meetings across the city. I remember feeling sick sitting in the St. Louis Public Radio newsroom reading the Justice Department’s findings on the Ferguson police’s victimization of its black citizens. I sat in a St. Louis Public Radio studio commenting on the decision not to prosecute Officer Darren Wilson, while the TV screens in the corner of the studio lit up with footage of fires in Ferguson.

And I’ve seen how events in St. Louis tied into national retreats on civil rights when our presidents catered to racial stereotypes to win elections. Richard Nixon crafted a Southern Strategy to create a solid GOP South. Ronald Reagan opposed the 1964 Civil Rights Act, campaigned against “welfare queens,” tried to give segregationist schools like Bob Jones University tax breaks and systematically dismantled civil rights enforcement. GOP leaders across the country passed voting restrictions that disenfranchised voters like the literacy tests and poll taxes of the segregated South.

What has changed for me as a result of Ferguson and the 1619 project is that what once seemed like a triumphal, unstoppable march toward full equality now is revealed as a centuries-long, bare-knuckle fight where the celebrated champions of freedom and equality – Jefferson and Lincoln – are exposed for their hypocrisies. That long arc bending toward justice has bent so very slowly and so many hundreds of thousands of people have died along the way – from Civil War battlefields, to a century of lynchings, to the basement of the 16th St. Baptist church, to the streets of Ferguson. America has had to be dragged kicking by abolitionists and civil rights advocates to fulfill its promises.

All Men – We the People

America’s two most powerful proclamations of national purpose are the Declaration of Independence’s “all men are created equal” and the Constitution’s preamble, “We the People.” These short, dramatic statements of the equality, power and freedom of the common man are the reason America is a beacon to the world.

Yet the meaning of those words was uncertain at the time they were written, at the time of the Lincoln-Douglas debates on the eve of the Civil War and remains so today in this era of Black and Blue Lives Matter.

Jefferson, who wrote that all men are created equal, owned more than 180 slaves and had six children by his slave Sally Hemings. In addition, all 13 of the original colonies protected slavery at the time of the Declaration.

Jefferson’s first draft of the Declaration explicitly criticized the king for slavery. It read:

“He has waged cruel war against human nature itself, violating its most sacred rights of life and liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him …Determined to keep open a market where men should be bought and sold, he has prostituted his negative for suppressing every legislative attempt to prohibit or restrain this execrable commerce.”

But the passage was cut out, the biggest deletion made from the draft document. Jefferson wrote that the passage was struck in “complacence to South Carolina and Georgia who had never attempted to restrain the importation of slaves. Our northern brethren also I believe felt a little tender, because…they had been very considerable carriers of them.”

The simple preamble to the Constitution – We the People – made clear the document was for the common man, not handed down by the divine right of a king. But was everyone included in We?

Based on the values of the times, several groups were clearly not part of “all men” or “We.” Women for example. Also, children, Indians and what people of the time called “imbeciles.” In addition, eight of the original 13 states were slave states.

One mistake Hannah-Jones made in her New York Times essay on the history of this time was to claim that “Conveniently left out of our Founding mythology is the fact that one of the primary reasons the colonists decided to declare their independence from Britain was because they wanted to protect the institution of slavery.”

An African-American historian the Times engaged to fact-check the essay had warned against this overstatement, but was ignored. Leslie M. Harris, history professor at Northwestern, explained, “Although slavery was certainly an issue in the American Revolution, the protection of slavery was not one of the main reasons the 13 Colonies went to war.”

Hannah-Jones now acknowledges her overstatement and The Times added an Editor’s Note in March stating: “a desire to protect slavery was among the motivations of some of the colonists who fought the Revolutionary War, not among the motivations of all of them.”

What can be said for certain is that the Founding Fathers were entirely aware that they were hedging their great promises of freedom and equality as part of a hellish bargain with slaveholders.

The most important historical moment of the racial history of St. Louis, Missouri and Illinois – the Dred Scott decision and the Lincoln-Douglas debates that followed – establish beyond a doubt that the Founding Fathers failed to include blacks in their experiment in freedom and equality.

Seventy years after the Constitution, the Supreme Court ruled in the Dred Scott decision that blacks were definitely not included in We the People – whether they were free or enslaved. They are “so far inferior,” wrote Chief Justice Roger Taney, “that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.”

The Dred Scott decision was one of the most hotly debated issues in the summer of 1858 as Lincoln and Douglas ranged from Ottawa in the north to Jonesboro in Little Egypt, and from Charleston in the east to the final debate in Alton.

Douglas argued that the Founding Fathers never meant to include blacks when they wrote the Declaration of Independence or the Constitution. They believed that the United States could endure “forever” half slave and half free, he said.

But Lincoln disagreed. Lincoln pointed out in the last debate at Alton that the Constitution never used the word slavery but instead referred to it in “covert” language so as not to blemish the document they wanted to stand for the ages. This showed, Lincoln said, that the Founding Fathers thought slavery would gradually vanish.

A shocking thing about reading the Lincoln-Douglas debates in 2020 is they often weren’t the high-minded political debates that history texts advertise.

The debates are stained from Ottawa to Alton by appeals to the racism of whites.

Douglas painted the a picture of hundreds of thousands of freed Negro slaves from Missouri turning the beautiful Illinois plain into a Negro “colony.” In Jonesboro he ridiculed abolitionist friends of Lincoln’s, “Why, they brought Fred Douglass to Freeport,” he said, “when I was addressing a meeting there, in a carriage driven by the white owner, the negro sitting inside with the white lady and her daughter.”

“Shame” murmured the crowd.

As for the Great Emancipator, he was no emancipator. His preference was to send freed slaves back to Africa. But certainly he would not support equality between blacks and whites.

At Charleston he said: “…I am not, nor ever have been, in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races, [applause]-…I am not nor ever have been in favor of making voters or jurors of negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office, nor to intermarry with white people; and I will say in addition to this that there is a physical difference between the white and black races which I believe will forever forbid the two races living together on terms of social and political equality. And inasmuch as they cannot so live, while they do remain together there must be the position of superior and inferior, and I as much as any other man am in favor of having the superior position assigned to the white race.”

No one should have been surprised when Lincoln failed at first as president to free the slaves, then freed only slaves in Confederate states where he was powerless and – as Hannah-Jones recounted – invited African American leaders to the White House to pursue his plan of sending freed slaves back to Africa.

Forgetting Is Our National Pastime

No one questions any longer whether men in the Declaration and We in the Constitution include blacks. But the events of Ferguson demonstrate African Americans are not treated equally by the law on the streets by America’s towns and cities in the year 2020.

The unfolding events in Brunswick, Ga. reinforce that truth. It took Georgia authorities four months to charge a former law enforcement officer and his son with murder for shooting Ahmaud Arbery, a 25 year old African American killed while jogging near his home.

Nothing that has happened in St. Louis during the 21st Century has been as important as the events of the Ferguson protest and its aftermath.

The Justice Department found the Hands Up, Don’t Shoot claim of the activists at the protests was a myth when deciding not to charge Officer Darren Wilson for killing Brown. But the Justice Department also found a scandalous pattern of unconstitutional police practices where the mostly white police department abused the rights of black citizens.

The most important impact from Ferguson was what followed Brown’s death – the sweeping legal reforms, the election of reform prosecutors across the country and a reawakening of Americans to the persistence of racial inequality.

Gardner, elected by Ferguson activists as St. Louis’ first black prosecutor, faces some justified criticism for the way she has administered the circuit attorney’s office, but race plays an important role.

The action that got Gardner in the most trouble was filing criminal charges against former Gov. Eric Greitens. She filed criminal invasion of privacy charges against Greitens for allegedly taking a photo of his partially nude mistress tied up in his basement.

At first, there seemed to be no racial angle. But Greitens hired powerful establishment lawyers, including Democrat Edward Dowd, to represent him. A complaint by Dowd led to the appointment of a special prosecutor to investigate Gardner’s office for alleged perjury by a Gardner investigator. The special prosecutor appointed in that ongoing investigation was Gerard Carmody. Gardner says Carmody and Dowd are part of an old, white boy’s club. Both have been friends since they graduated in the class of 1967 at Chaminade.

Gardner contends in a lawsuit, based on Section 1985 of the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871, that elements of the white police union and white legal establishment have set up the “trappings of a legitimate criminal investigation” to punish her for the Greitens prosecution.

The suit says the white legal establishment “leveraged their control of the Special Prosecutor’s office to set up many of the trappings of a legitimate criminal investigation, complete with subpoenas and a grand jury. But the true purpose… is to thwart and impede her efforts to establish equal treatment under law for all St. Louis citizens…; to remove her from the position to which she was duly elected—by any means necessary—and perhaps to show her successor what happens to Circuit Attorneys who dare to stand up for the equal rights of racial minorities in St. Louis… The United States Congress passed the Ku Klux Klan Act during the aftermath of the Civil War to address precisely this scenario: a racially-motivated conspiracy to deny the civil rights of racial minorities by obstructing a government official’s efforts to ensure equal justice under law for all.”

Gardner probably won’t win her Ku Klux Klan Act lawsuit. She has made mistakes as a prosecutor. Proving a conspiracy among Gardner critics may be impossible and the Supreme Court has been reluctant to approve of expansive use of the KKK law.

But Gardner and the progressive prosecutors around the country who support her believe white police union officials and powerful white judges and lawyers have abused their power to undermine the efforts of St. Louis’ first black prosecutor to bring greater equality to law enforcement on the city streets.

The contrasting reactions of the majority white police union and majority black police association illustrate the persistence of race – in fact the mere existence of separate white and black police groups in 2020 is a powerful statement about race.

The majority white St. Louis Police Officers Association said: “‘This is a prosecutor who has declared war on crime victims and the police officers sworn to protect them. ‘She’s turned murderers and other violent criminals loose to prey on St. Louis’ most vulnerable citizens and has time and time again falsely accused police of wrongdoing. The streets of this city have become the Killing Fields as the direct result of Gardner’s actions and inaction.’”

The majority black Ethical Society of Police disagreed: “We have repeatedly highlighted the disparities along racial lines with discipline, promotions, and job placement; therefore, the Circuit Attorney stating she has experienced racial bias at the hands of some SLMPD officers is far from ‘meritless.’”

So, yes, race plays a central role in the life of this city, this state and this nation, just as it has during our entire lives and the entire life of the nation.

Race is also playing a role in the deaths of our citizens. Few events have so clearly shown the deadly consequences of the inequalities that persist as has Covid-19s high toll among blacks.

The heavy toll Covid-19 has taken on the African American community tells the story of the poorer health, lower life expectancy, inferior health care and vulnerable positions that African Americans occupy in our society. Sixteen of the first 19 deaths of St. Louisans were black. Just under 50 percent of the St. Louis County deaths were African American.

Jason Q. Purnell of Washington University’s Brown School found in his 2014 “For the Sake of All” report that the affluent, mostly white population that lived in the 63105 zip code running through Clayton and Washington University lived almost two decades longer than mostly black population living one digit up in 63106 on St. Louis’ near north side.

That was because of race, segregation, poverty, which makes blacks more vulnerable even to the undifferentiated enemy of a pandemic.

Purnell once said this in an interview:

“The most difficult challenge that we uncovered in this work and has slapped me in the face over and over again is segregation….if you asked me one thing we need to tackle it would be segregation. I’ve begun saying that St. Louis is an innovator in segregation.

“…As an African-American man it makes my blood boil. So much of the current conversation is why don’t people just try harder, but people have been trying hard for a century and at every turn they are blocked… by personal prejudices, structurally blocked by law and politics.

“They say baseball is the national pastime. Forgetting is the national pastime in the United States. There is nothing more quintessentially American like forgetting. We have no sense of the sweep of history and how current day outcomes are shaped by these baked in disadvantages…that you can’t bootstrap your way out of.”

William H. Freivogel is the publisher of Gateway Journalism Review. This story published on the cover of the Spring 2020 print edition of Gateway Journalism Review.

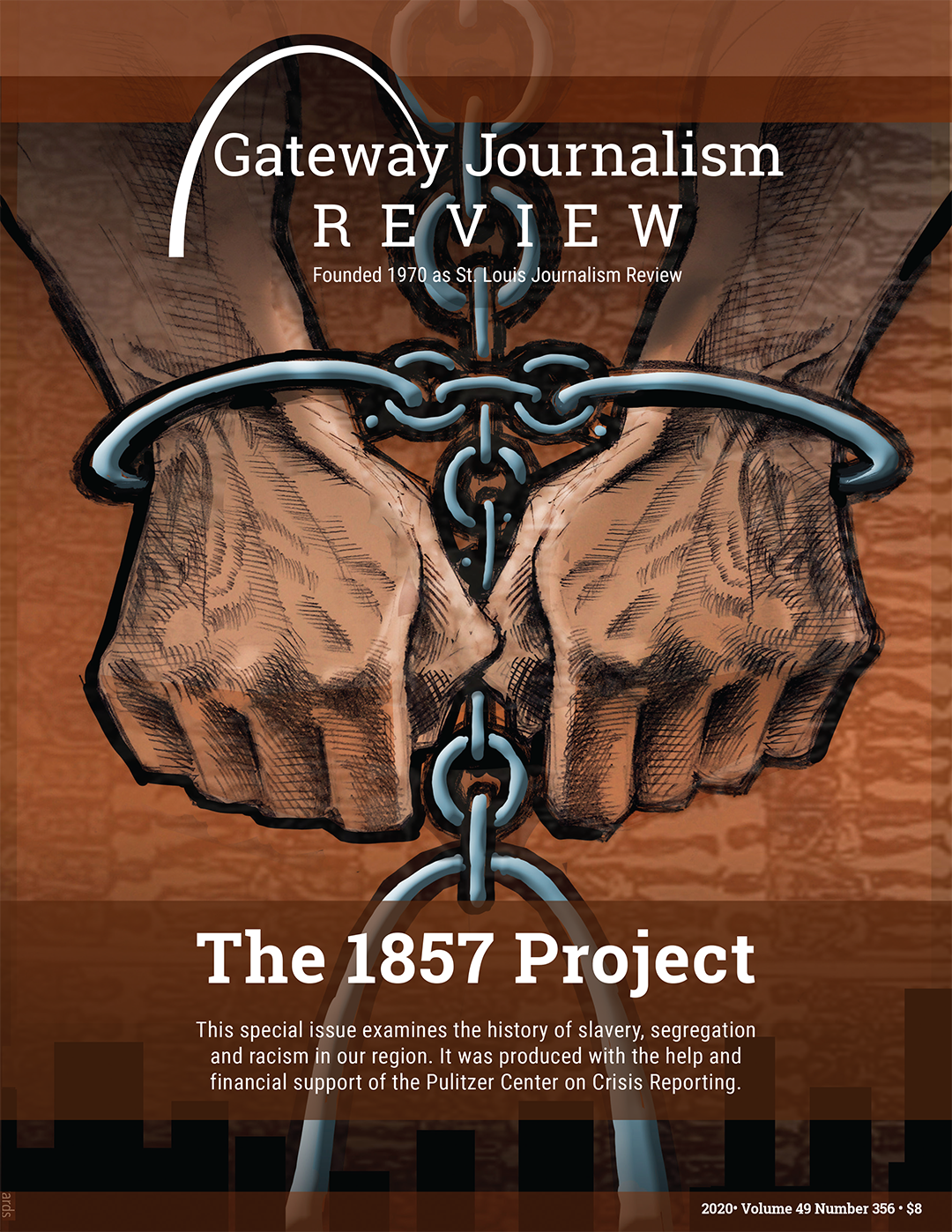

The spring 2020 print issue on the history of slavery, segregation, and racism in our region was produced with the help and financial support of the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.