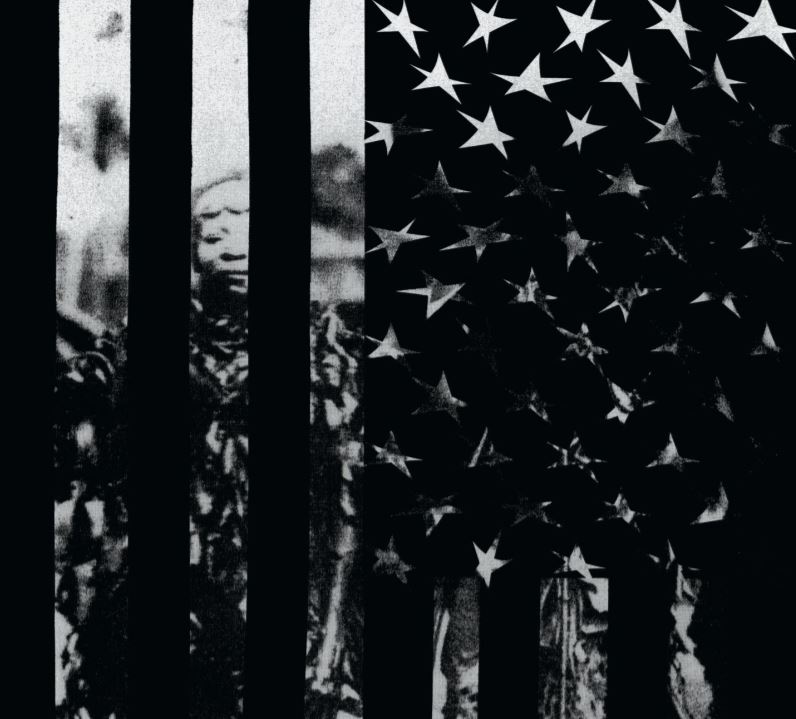

On Tuesday, August 13, a sold-out crowd packed the TimesCenter in New York City for a program marking the launch of The New York Times Magazine’s ‘1619 Project,’ which explores the continuing legacy of slavery in America. The issue, which was the brainchild of New York Times Magazine staff writer Nikole Hannah-Jones, is timed to coincide with the 400th anniversary of the arrival of 20 to 30 enslaved Africans in colonial Virginia. Many of the contributors to the issue presented and discussed their work in a two-hour program emceed by editor Jake Silverstein and Hannah-Jones. Many hundreds of viewers from around the world also livestreamed the event online.

Poets Yusef Komunyakaa, Eve Ewing and Tyehimba Jess read from their work

“Pretend I was there with you, Phillis, when you asked in a letter to no one:/How many iambs to be a real human girl?/Which turn of phrase evidences a righteous heart?” read writer and sociologist Eve Ewing. Ewing’s poem, about Phillis Wheatley, a 20-year old enslaved woman in Boston in 1773 who became the first African-American to publish a book of poetry, is one of the literary works featured in the issue.

In the opening performances, poets Tyehimba Jess and Yusef Komunyakaa also read from their poems featured in the issue. “They remembered themselves/with their own words/bleeding into English,/bonding into Spanish,/singing in Creek and Creole,” Jess read from his poem about the American troops’ attack on Negro Fort, a stockade in Spanish Florida left to the Black Seminoles. “How often had he walked, gazing/ down at gray timbers of the wharf,/as if to find a lost copper coin?” Komunyakaa read, imagining the life of Crispus Attucks, a fugitive from slavery who worked as a dockworker and became the first American to die for the cause of independence after being shot in a clash with British troops.

Nikole Hannah-Jones on the conception of ‘The 1619 Project’

Hannah-Jones had pitched the idea for an entire issue dedicated to exploring the legacy of slavery in contemporary America to her editors at The New York Times Magazine. When doing so, she explained, she highlighted several modern phenomena—from capitalism to violence in the criminal justice system—and argued that they trace their roots back to slavery. “The legacy is part of everything in our society; it doesn’t only impact black Americans but all of us who are Americans,” Hannah-Jones said.

“What if I told you that the year 1619 is as important to the American story as the year 1776? What if I told you that America is a country born both of an idea and a lie?” she asked. She remembered how she was taught about slavery in school: “Slavery was always taught as something marginal to the American story; it was mentioned in history books because we had to talk about the Civil War,” she said.

She knew that the anniversary of the arrival of the first enslaved Africans to Virginia in 1619 would pass in many households in America without notice. But, she said, “this anniversary is the reason we even exist as a country...we would not be the United States were it not for slavery.”

“The dizzying profits from enslaved labor paid off war debts, helped finance some of our most prestigious universities...Wall Street in New York is named after the wall upon which enslaved people were bought and sold,” she continued. “When Thomas Jefferson wrote that all men are created equal, and endowed by the creator with unalienable rights...he owned 130 human beings who would enjoy none of those rights,” she said.

Collaboration with the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture

In addition to the issue of the magazine, a special broadsheet section of the August 18 New York Times made in collaboration with the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture will examine the genesis of the transatlantic slave trade. Onstage, Hannah-Jones spoke with Mary Elliott, who co-curated the slavery and freedom exhibit at the museum and helped with picking the objects included in the insert.

Elliott explored the meaning and significance of three objects found in the exhibit and included in the special section. “We use objects to tell a story,” said Elliott, showing an image of a sugar cane cutter on the projector. “The transatlantic slave trade driver was sugar...it was a deadly commodity that altered women’s reproductive systems,” she said.

Poets Komunyakaa, Ewing, and Jess on their inspirations

“We wanted to use imagination to find our way into the past. As part of this project, we asked creative writers to imagine their way into key moments on the historical timeline of the past 400 years,” New York Times Magazine editor Jake Silverstein said, describing the several creative works from poets, playwrights, and fiction writers in the magazine.

Silverstein joined Tyehimba Jess, Eve Ewing and Yusef Komunyakaa to talk more about the poems they each read earlier. Each of the poets picked the moment they wanted to write about from an expansive timeline. Komunyakaa wrote about Crispus Attucks, a fugitive slave who died after being shot in a clash with British troops. “What was interesting to me about this individual is that he seemed so ordinary, but yet he was an escaped slave. He had a certain kind of spirit and tenacity that he could push against things...he knew what freedom was.”

Ewing chose to write about Phillis Wheatley because she “felt a sense of obligation” to Wheatley as a black female poet. Ewing explained that we hear the disparaging voices of Hume, Kant, and Jefferson throughout the poem, and the idea that they reiterated that black women, and black people, were not intellectually capable of making art. “Nobody believed a black woman could write poetry,” Ewing said.

Jess focused his poem on the American troops’ attack on Negro Fort, a stockade in Spanish Florida left to the Black Seminoles, because, he said, he was upset he didn’t learn about it when he was taught about slavery in school. “It’s a fascinating story that runs all the way up to American history until today,” he said.

Panel with Wesley Morris, Linda Villarosa, and Jamelle Bouie

Hannah-Jones spoke with New York Times critic Wesley Morris, journalist Linda Villarosa, and New York Times columnist Jamelle Bouie, who all contributed essays to ‘The 1619 Project’ issue.

Bouie, who wrote an essay about power in America, specifically histories of obstruction, said he spent a large amount of time researching the legacy of John C. Calhoun, one of the most vociferous defenders of slavery in the runup to the Civil War. The anti-majoritarian ideology we see in America today, Bouie said, can be traced back to Calhoun’s influence on American politics.

Villarosa wrote about the discrimination against black people in our current healthcare system, tracing it back to slavery. Villarosa read the story of John Brown, an enslaved man on a plantation in Georgia in the 1820s-40s who was loaned to a medical enslaver. She examined the ideology of Samuel Cartwright, a physician who presented the narrative that black people are different from white people, and have diminished lung capacity.

Morris explored the legacy of black music in America. He spoke about the influence of Detroit's Motown. “If you think about 100 years of [living as a] sub-human, unworthy of the vote, impervious to pain…[listening to this music] was the one thing you [could] do to combat that.”

Moving it forward

In the Q&A portion of the evening, the contributors who spoke earlier in the program returned to the stage.

Villarosa reflected on the process of writing her essay. She remembered that she was frying fish for dinner after she finished the piece and got a second-degree burn. “It hurt so much, [then] I thought, this was nothing compared to what John Brown had to endure...I realized, I had to put this in the essay, the pain and anger, I had to write it in.”

Ewing noted that ‘The 1619 Project’ also reminds us that all institutions must hold themselves accountable. "We need to ask, how are we replicating these dehumanizing narratives everyday? We’re at risk of undermining great work if it sits in parallel [to narratives] that continue to dehumanize black people."

“We knew how important this was,” said editor Jake Silverstein about the extensive work that the entire staff poured into the magazine.

At the end of the program, he thanked the Pulitzer Center and addressed teachers around the country. “We want you to join us in this work, especially those of you who work with education,” he said. He mentioned the sheet in the magazine highlighting the Pulitzer Center’s education materials. “If you’re an educator, a parent, [these are] great education materials, and we’re very much looking forward to seeing what young people do with this project and how they can be the ones to move it forward.”