The following reflection was written by Abigail Henry, who teaches African American History in Philadelphia, PA. Henry shared the book The 1619 Project: A New Origin Story with her classes as part of the Pulitzer Center-Penguin Random House 1619 Pilot Program. Henry is also part of the inaugural cohort of The 1619 Project Education Network.

Fugitive Pedagogy by Jarvis R. Givens is a wonderful book about the history of Carter G. Woodson and Black education theory and teaching practice. In the text, Givens argues that “Black people’s political clarity meant that they understood their teaching and learning to perpetually take place under persecution, even as they created learning experiences of joy and empowerment.” He also describes many specific instances of the targeting of Black teachers that resonate with me as a Black teacher continuing to work in the current politicized education climate.

I expressed this to Ismael Jimenez, director of social studies for the School District of Philadelphia (SDP), after I started reading the book and stated how relevant the book felt to the work we have been doing in updating Philadelphia’s historic African American History curriculum. Jimenez agreed and stated that for Black teachers like me, reading the book can be professionally “liberating.”

SDP is approaching their 20th Anniversary of mandating African American History. For this anniversary, they are working on updating their curriculum with the goals of providing a more African-centered worldview (one focused on historical accounts of Black success removed from the umbrella of white supremacist structures) and increasing opportunities for students to encounter diverse Black perspectives. An additional goal of the course is to celebrate Black humanity, dignity, and greatness without reducing such lived experiences within the mold of oppressive systems.

Jimenez describes Africana studies as “a scholarly tool for understanding the world through the transtemporal African-centered worldview and seeks to define a paradigm not confined by Eurocentric definitions.” I have been delighted to be able to work with Jimenez in utilizing my experience as an African American History teacher in West Philadelphia and as an alumni of Pulitzer Center’s 1619 Project Education Network to help improve this special curriculum.

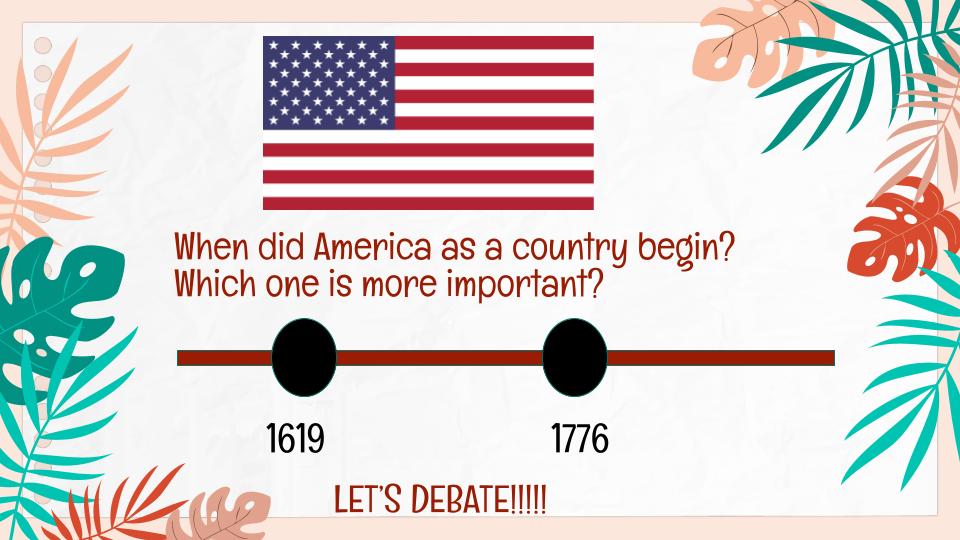

I initially wrote 2 units as a part of my 1619 Education Network fellowship. The first one, titled “Atlantic Slave War: Investing the Origins and History,” reframed the Atlantic slave trade, in alignment with Vincent Brown’s work, as a “war” in which enslaved Africans always resisted. The second unit was titled “Evaluating The 1619 Project’s Claims.” This unit asked students to analyze key claims in Nikole Hannah-Jones’ “Democracy” and compare them to common claims made about the importance of the 4th of July. Incorporating sources and lessons from both units into the SDP curriculum allowed me to focus not just on the legacy of slavery, but also on the resistance to the system of enslavement.

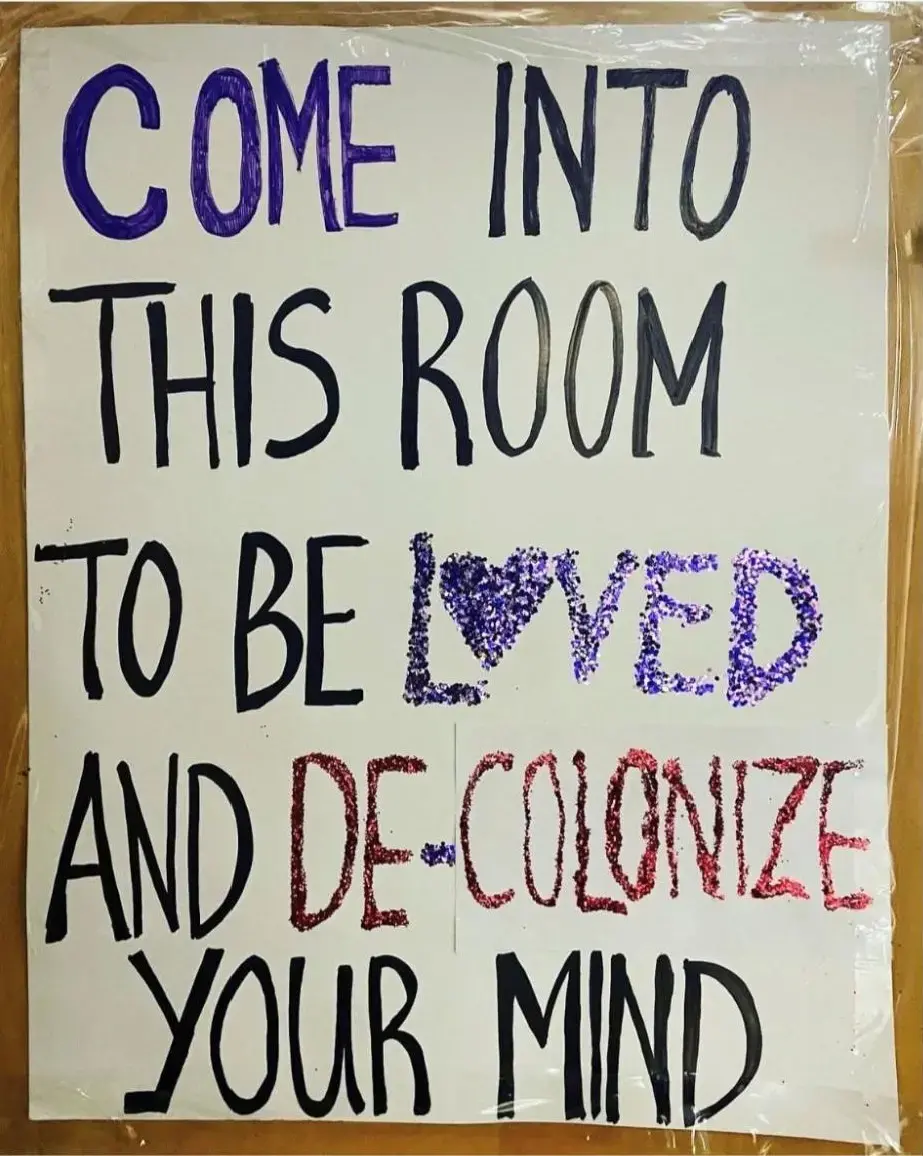

By the time I was brought on to help update the SDP’s African American history curriculum, I already had one year of experience bringing The 1619 Project to life in my classroom. The 1619 Project helped me to truly “decolonize” my history teaching. There has been a lot of recent discourse about confronting existing power structures that have negative impacts on student learners. However, there are few examples of what decolonization realistically looks like in the classroom each day.

The instructional guide for SDP’s revised curriculum will also address decolonization. In it, Jimenez states that by decolonizing the social studies curriculum, “Educators can implement an educational curriculum that challenges and seeks to eliminate the colonial and imperialist perspectives and assumptions that have influenced and shaped traditional educational systems. By humanizing the classroom in this way, educators can also create a more democratic and equitable learning environment.”

The 1619 Project helped me decolonize my classroom by centering America’s origin story on the perspective of enslaved Africans and the lived experiences of African people prior to enslavement. This year, prior to reteaching my unit on 1619’s key claims, I challenged the discourse on America’s founding to include an additional Pan-African perspective. SDP’s focus on truly celebrating African history—the diversity of African cultures, peoples, resources, religions, languages, and more—provides students with the opportunity to fully understand the history and glory of the African diaspora. Therefore, when discussing the key claims made in 1619, students are able to also highlight the importance of the cultural retention of the enslaved.

In the SDP units that I worked on, I selected the lessons and sources that student’s found most engaging and robustly rigorous from my 1619 Education Network curricula. In addition to repurposing those lessons and strategies, I was able to utilize The 1619 Project to meet the goals of the SDP’s African American History revamp in the creation of new unit material. I chose from The 1619 Project excerpts and media for students to evaluate the economic impact of slavery and the ongoing impact of white backlash to Black resistance.

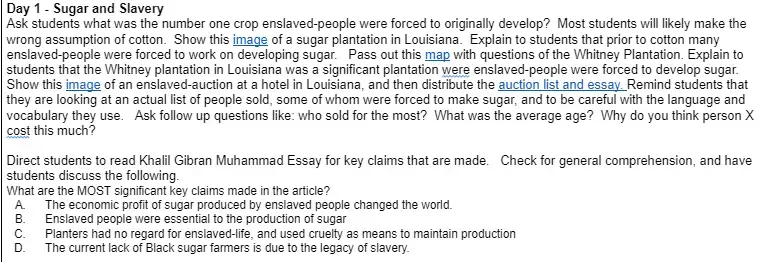

Khalil Gibran Muhammad’s “Sugar” essay, combined with appropriate primary sources, provided a successful inclusion in SDP’s unit titled “Development of the Modern World System.” This unit challenges students to connect the financial motivations of the slave trade with the expansion of Western European power. Many students make the false assumption that European profits were based solely on the enslaved production of cotton. By incorporating Gibran’s essay documenting the dehumanizing means enslaved Africans were forced to break down sugar cane, along with an enslaved auction list from one of America’s largest sugar labor camps, students expanded their knowledge regarding the economic market of slavery.

| “From it’s inception in 1526 to its legal end in 1876, the atlantic slave trade completely dehumanized the citizens of Africa. In all cases, they were traded simply as property within a large market by many within the Americas. A tab of the Whitney Plantation slave auction within [Louisiana] shows just how big of a market these slave auctions were.” |

It was extremely rewarding to have the opportunity to build on students' essential understanding of The 1619 Project with a three-lesson mini-unit culminating in a Socratic seminar on reparations, something I’d never taught before. One of these lessons is incorporated into the last unit of SDP’s curriculum titled “Defining Black America and Its Future.” Without reminders from me, students were able to cite key statistics, sources, and understandings from The 1619 Project into arguments for and against reparations.

In my attempt to decolonize the classroom, I frequently seek the celebration of humanity, empathy, and respect for diverse perspectives. I started the conversation about reparations by asking students, “If someone caused you a lot of trauma and pain, would you want that person to apologize?” For my students in West Philadelphia, approximately 80% of them responded “No, their actions after are more important.” A rich discussion followed this question, and prepared them to fully engage in watching Nikole Hannah-Jones describing her argument for reparations.

In a blog previously published by the Pulitzer Center, I argued that I perceive the anti-critical race theory rhetoric as centered on a falsely colonized discourse. This can not be more evident than in any hesitation around teaching about reparations. My students were 100% African American or of African or Afro-Caribbean descent this past year. Not all of them supported monetary reparations. Yet given their knowledge of the year of 1619, none of them could comprehend why some social studies classrooms are not allowed to engage with even a discussion regarding reparations.

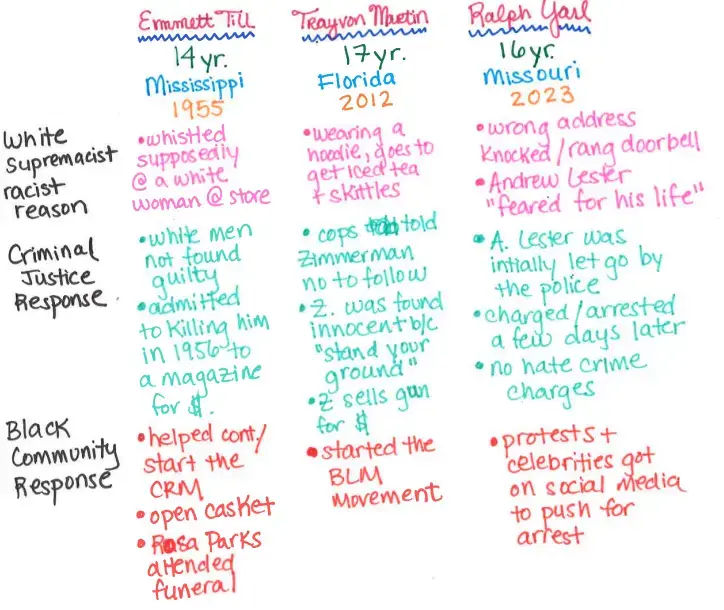

In addition to studies on the economic system and the impact of slavery in America, incorporating The 1619 Project into the SDP curriculum means improving instruction on the relationship between Black resistance and white fear. Leslie and Michele Alexander’s “Fear” essay in The 1619 Project: A New Origin Story is one of the more accessible sources for students to read excerpts. The SDP's focus on resistance throughout the yearlong curriculum allows “Fear” to be a successful supplement. Students are able to compare and contrast the historical context of the Haitian Revolution, Bacon’s Rebellion, the New York Slave Revolt, to the rise of the KKK, Emmett Till’s murderer, and to the shooting of Ralph Yarl.

In each of these topics students engaged in appropriate conversations about how Michele Alexander and Leslie Alexander argue that “The specific forms of repression and control may have changed over time, but the underlying pattern established during slavery has remained the same. … Nothing has proved more threatening to our democracy, or more devastating to Black communities, than white fear of Black freedom dreams.” Students' understanding of the authors’ claims helped them also make further connections between acts of violence, the criminal justice system, and the social movements.

| “In history, Enslavers feared Black rebellions leading to violent responses to Black people not submitting. In the excerpt from “Fear” by Leslie Alexander and Michelle Alexander in the [1619 Project] book the author stated, “The deep-seated, gnawing terror that Black people might, one day, rise and demand for themselves the same freedoms and inalienable rights that led white colonists to declare the American Revolution has shaped our nation’s politics, culture, and systems of justice ever since.” As a cost and fight for freedom, people of African descent never gave up standing for what they believed in no matter how hard it became.” |

In Givens’ conclusion to Fugitive Pedagogy, he describes such pedagogical methods as being “grounded in the assertion that those who have been marked as slave / Black in the modern world might initiate a new ceremony of knowledge … Developing alternative scripts of knowledge and physically subverting imposed protocols for learning have long been defining features of black educational heritage, a heritage whose early emergence began in the cells of slave castles …”

By expanding on my understanding of The 1619 Project, and incorporating it into the SDP’s curriculum, Jimenez and I are sincerely attempting to decolonize history education for over 120,000 students to encounter during their experience in an African American History class. It is more than exciting that despite the current anti-woke politics of education, the Philadelphia School District is truly leading the charge in providing students with an attempt to decolonize the social studies curriculum.