The following reflection was written by Adriana Bland, who is an educator with the out-of-school time nonprofit Global Kids in Brooklyn, New York. Bland was part of the Pulitzer Center's 1619 Project Afterschool Partnership program during the 2022-23 school year, which culminated in partners facilitating activities that engaged students in learning about the legacy of enslavement and the contributions of Black Americans in their programs.

Global Kids is all about examining critical human rights issues domestically and globally, and my program is located in Brooklyn, serving a majority of Black and brown high school students. Our students are active in their communities and come with a hunger to make the world a better place. When presented with the opportunity to be in the Pulitzer Center's afterschool cohort, I knew that my students would be more than engaged with The 1619 Project. I knew that they would come with questions, concerns, ideas, and suggestions for how to apply what was learned to their daily lives. I always want my students to feel important and to feel heard. I want them to understand that their history (my history) won’t be disposed of as long as we have something to say/do with it!

The learning objectives for our engagement were the following:

- Identify the ways in which erasure can be used to oppress people and to resist oppression.

- Explore examples of poems that use erasure as a means of resistance.

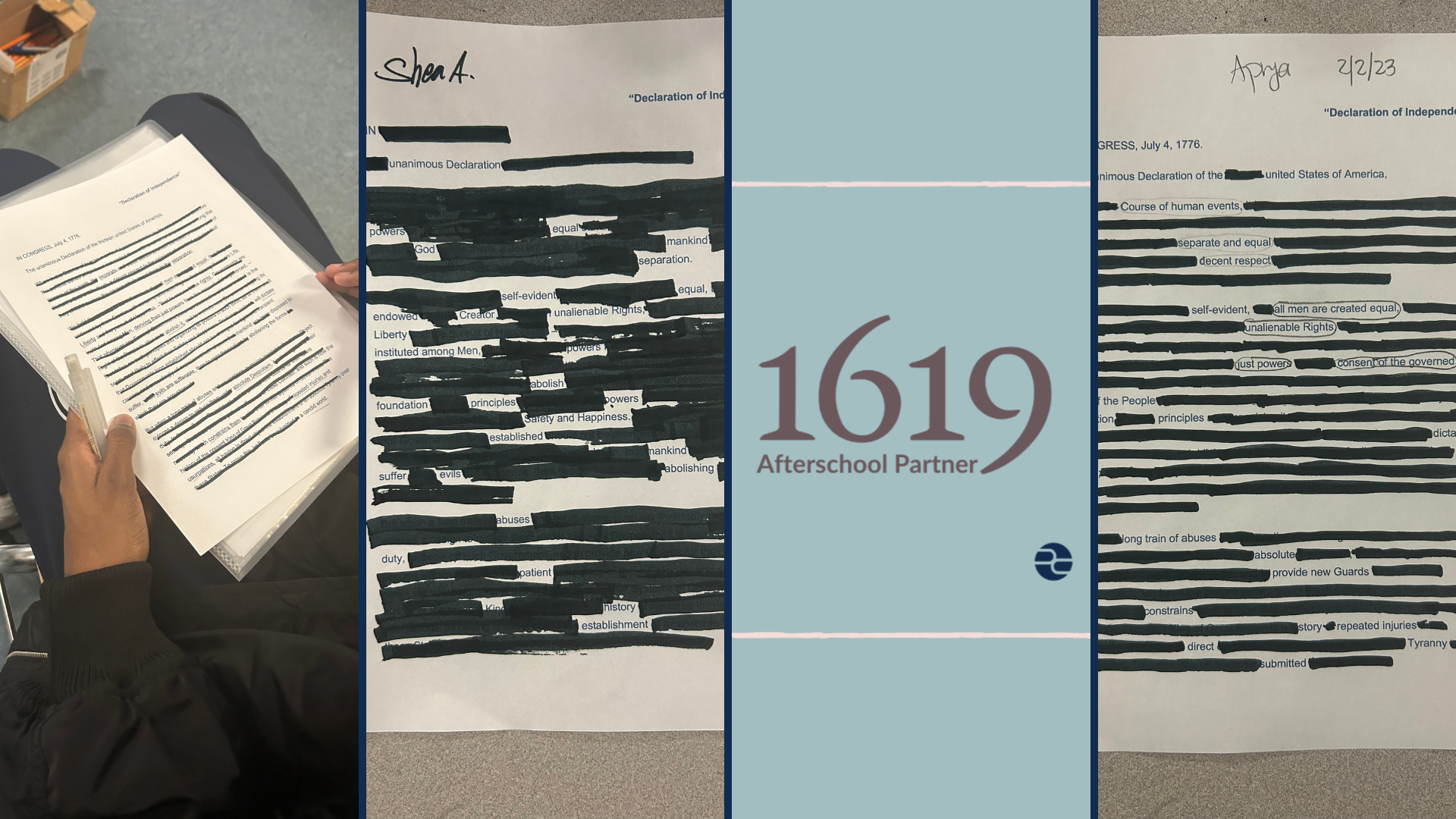

- Create original erasure poems.

I started the workshop with a human barometer—an activity designed to see where student opinion lies. I instructed students to move to the side of the room that best represented their associations with the term “erasure” on a scale of “negative,” “positive,” or “mixed.” Students learned about the term “erasure” and how it applies to the history of African American people. When asked about what sort of feelings or connotations arise when hearing the word, most students expressed that the term was more negative in nature. A lot of the conversation centered around culture and how an erasure of culture is meant to “strip people of power and knowledge.”

For the next activity, I played a video in which Nikole Hannah-Jones introduces The 1619 Project and held a discussion. The main activity included reading and analyzing existing erasure poetry (Reginald Dwayne Betts - Fugitive Act). We discussed impact and messaging before moving on to create our own erasure poems, using the Declaration of Independence.

Being an afterschool program educator, it made me really think about how for some of these students, I may be their only source for connecting with their own history. My students were excited and passionate to learn about a year they had never heard of before...It was cool to see the eagerness in their eyes to explore the unknown.

In preparing and facilitating these activities, I learned how much students are hurting from the exclusionary curriculum they are presented with. They were fired up! A mix of shock as well as anger could be seen across their faces. “Why doesn’t the school care about my history?” “Why do we only learn about slavery?”

Being an afterschool program educator, it made me really think about how for some of these students, I may be their only source for connecting with their own history. My students were excited and passionate to learn about a year they had never heard of before. Additionally, many of them had either never heard about erasure poetry or had never created their own. It was cool to see the eagerness in their eyes to explore the unknown. My advice to other educators who want to teach 1619 is to meet students where they are. What do they already know? What do they want to know? Why do they want to know it? Just because students aren’t actively showing their interest in a topic doesn’t mean that they don’t care. For some, it’s just a matter of not knowing at all.

A week after facilitating the workshop with my students, we attended the Black Lives Matter at Schools rally to advocate for their list of demands. One of those demands included mandating Black history and ethnic studies. When asked why this particular demand was important and necessary, one student brought up how we learned about erasure. He mentioned how by not teaching students about their history, we minimize experiences. It was really awesome to see them connect lessons to their daily lives and advocate for an end to erasure.